NABJ’s Trump panel diminished, disrespected the legacy and audience of the Black press

By selecting no moderators from the Black press to interview Trump, the largest gathering of Black journalists in the nation chose a mainstream, majority-white audience over Black communities.

By 2017, I’d come around to accepting, not just coping, with the latest phase of my industry’s inequity. The journo hustle has an expiration date. That date comes quicker for oddities in the industry like me, a POC immigrant journalist from the working class who’s driven to produce news for low wealth and/or communities of color. Since the early 2000s, I’d been putting in the work.

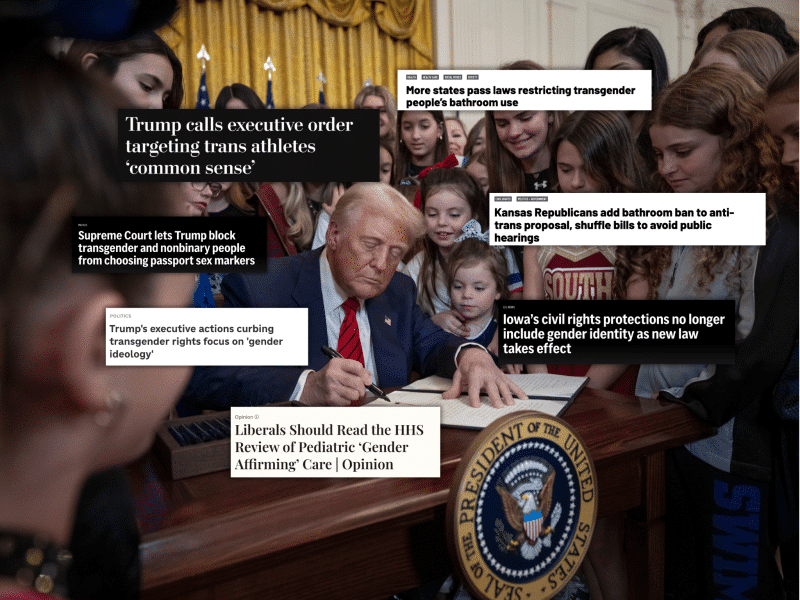

I stopped in 2017 because I learned that “the media system” — not once a part of my graduate-level journalism education — determined far more of my actual experience and choices as a nontraditional journalist than knowing the craft. Looking back, it makes sense for that year to mark the end. I’d just spent the year watching a longshot candidate with TV-appeal, Donald J. Trump, ascend to POTUS, in large part, because of how mainstream national media functioned.

A few weeks ago, Trump, again, triggered my memory of that time, this lesson. I opened my inbox to an announcement to members that in two days, the current presidential candidate would be interviewed on stage at the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) annual convention. I immediately checked the moderators list. When I saw their outlets, it struck me that NABJ was doing what I and so many journalists of color do in our careers — and what I turned away from in 2017: produce news about non-white peoples for mainstream, majority white audiences.

The media system in which I worked and that my journalism school education ignored deprioritized the production of quality news for Black audiences. An individual reporter seeking to do the opposite is swimming upstream in a downstream flow. In other words, drowning.

After a lot of denial, I think I was helped along to that understanding by the stories where I interviewed Black children. One boy stands out. Through a translator, he spoke in a low, hesitating whisper while the sun roasted us on a Port-au-Prince rooftop a few months after the 2010 earthquake. So does the face of a teenage girl in the kind of tough spot that’s common if growing up Black in certain zip codes in Brooklyn.

It’s hard to shake a child whose bright eyes speak to you with trust and expectation. It’s hard, too, as a reporter, when you realize those eyes have already lost them. Their honest stares are coding: “What is it you think you’re accomplishing with your little pad?”

What indeed? When I obsess about audience as I do now, it’s because white Americans’ 20th century pursuit of segregation means that regardless of their class and ethnic differences, today’s white Americans still tend to cluster. They generally don’t live in the same neighborhoods as the subjects of my articles.

So, why gather news for them about Black and Latino subjects? Why answer their questions about Black and Latino subjects? Why not answer Black and Latino questions about each other and where they lived? Why not gather news for them so that they could, well, act on the reporting where they lived? I could never reconcile the disconnect.

Audience, or, who we produce journalism for, is like that one little spot on my head where my braids tend to itch. It indicates whom our media system assumes citizens to be.

Those gut checks would occasionally put me on pause after I published a social justice story about Black and/or Latino experiences — particularly as my outlet’s audience was more often white. I recognized that itch again reading the email about Trump’s NABJ appearance. Far from prioritizing Black communities as their audience, I think NABJ wanted to be newsmakers within the mainstream news cycle. They got that. I’m unsure what place-based Black communities got out of the Trump interview.

The interview hour itself was a story all its own. With 1,000 people seated, it started more than an hour late. When the interview started, Trump seemed grouchy. Ultimately, his handlers cut it short after 35 minutes. Highlights and behind the scenes activity are covered in Richard Prince’s Journal-isms newsletter.

But from the moment that email hit my inbox till the convention ended a week later that Sunday, I wondered at NABJ leadership, “What is it you think you’re accomplishing with your little pad?”

Related: Donald Trump’s NABJ appearance shows the limitations of both-sides journalism

It struck me, and others, that the disappearance of Black press outlets on the highest national stage was being perpetrated by the literal black press. In Chicago — arguably the historic heart of the crusading Black press. What’s more, Chicago is also, today, one of a handful of 21st century journalism ‘city labs’ in the nation. It is an early leader in experimenting with nonprofit newsrooms that, like their commercial predecessors, produce journalism and media by, with or for black and other communities of color — not about them, for majority white audiences in the surrounding suburbs. Whether from Black legacy press or the new nonprofits, Chicago isn’t exactly hurting for moderator talent.

None of the three moderators represented the Black press. Not one represented an outlet that privileges discussion, debate, and deliberation between, among, or that is culturally-specific to majority-Black audiences. If I posted up at the biggest Black churches or a Missy Elliott and Friends concert, I don’t think I could find 20 random news consumers who could properly identify what a Semafor, one of the represented outlets, even was.

Trump’s interview yielded no new news about him, his approach, nor his messaging. But the relevant question is: new news for whom?

I didn’t attend this year’s convention. Judging by social media posts and my own personal texts with friends, attendees sounded either frustrated, betrayed, or disappointed. They all had different reasons. But ultimately, a joyous reunion for journalists who often work in racially-isolating and difficult work environments — and the equally large number of journalism job seekers — opened under Trump’s signature cloud of chaos.

I’m left wondering at the point and purpose of a Black journalists’ organization that doesn’t platform a single Black Press outlet to interview a presidential candidate. I’m left wondering about NABJ’s role in solutions underway to (re)forge connection between news and place-based Black communities.

The Press Forward initiative, for example, pledged to move $500 million over the next 5 years into local news. That follows a growing trend of philanthropic funding of local nonprofit and some for-profit newsrooms. It’s a game of musical chairs in the commercial press; each year there are fewer chairs. NABJ could have used its platform and time in the national spotlight to advocate for Black audiences by elevating the Black press on their national stage. (Its press release says they offered media credentials to the Black press and “appropriate placement for coverage during the event.”) But NABJ’s priority lay elsewhere, with mainstream national news and its majority audience.

The week of the Trump interview, one of my play cousins in Alabama texted to ask, “What is going on with the black journalists?” This surprised me. She’s a busy Gen Z women’s basketball coach. On the Zoom call that she arranged, she said her TikTok feed was lit with clips from Trump’s interview, so much so she watched the entire thing. After, and then even more so, she was stumped. Why did NABJ invite him?

Both my cousin and her aunt, who joined our Zoom, wanted to know what new information they were meant to learn.

Then her aunt said, “Black people around the country have probably never even heard of a Black journalists’ association. This Trump interview is going to be their first impression.”

Carla Murphy is a journalist, media organizer and professor at Rutgers University-Newark.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director