What ‘Minari’ taught me about Asian American science journalism

In the throes of leading The Xylom, the movie affirmed to me the importance of having ownership over how Asian Americans are portrayed and what our news media landscape looks like.

In Minari, wrapped around a deceptively simple family film, was a metaphor for the titular plant. It’s widely considered “invasive” because it perseveres — despite being uprooted thousands of miles.

Like minari, or 水芹, as I knew it, I was also uprooted thousands of miles. To be exact, 8,398.

Growing up in Hong Kong, 水芹 was something regularly available in Chinese restaurants. When I moved to Atlanta in 2018, I was unable to connect the dots for a moment between 水芹 and water spinach, as it is called in America — my engineer brain did not yet have the vocabulary for the staple crops that we built our cuisines on.

What I also didn’t know at the time was that it was illegal to consume water spinach in the state of Georgia. “They’re treating water spinach like marijuana,” many Asian Americans thought.

The success of Minari has only added to the urgency of the many real-life discussions between passionate Asian Americans, our state’s increasingly diversifying policymakers, and informed ecologists. After the release of the film, Atlanta-area Asian grocers finally successfully petitioned Georgia state officials to legalize water spinach.

Coming from a STEM background, Minari jumped out to me as an agricultural story. The long journey to legalize water spinach in Georgia was as clear-cut an ecology story as one would get.

That’s part of why I started The Xylom in 2018: Everywhere I look, I see science stories that challenge what it means to be Asian American and to be seen as Asian American. (Everything, Everywhere All at Once quite literally involved a multiverse.) Asian American communities are not a monolith concentrated in large cities: We are concentrated in some of the most vibrant ethnic enclaves as we’ve been growing the fastest in Middle America, particularly in the Dakotas. We both speak some of the most commonly used languages in the world, while keeping alive some of the most isolated and culturally significant tongues.

As we’ve grown, I’ve found the hard part is continuing to create and nurture safe spaces where these very real, very nuanced, not always immediately visible stories are heard and told.

In the beginning of Minari, the first two decisions the Yis made as they started the family farm were to eschew county water and decline the services of a water diviner to locate the best groundwater source. They instead dug their own well to mixed results.

It’s tempting to reject our cultural upbringing and take what is around us, as simple as the clean water we drink and fertile soil we walk on, for granted. Those are pitfalls The Xylom’s Managing Editor Rhysea Agrawal and I try to avoid. We leverage our STEM degrees — hers in geological sciences, mine in environmental engineering — to edit and commission accountability-focused stories and combine it with our lived experiences as immigrants to connect with those who feel caught between worlds or slip between the gaps of distinct cultures.

The Xylom was rooted in my observation that many of the storytelling spaces in the United States were English-centric, clustered around big metros. (In March 2018, five months before I hopped on a flight to the U.S. I noted this in a blog, “I Can’t Speak Science with My Own Tongue”.) These were pre-COVID times when large gatherings were more commonplace at my favorite storytelling shows like The Story Collider or The Moth; to make these types of shows work, they had to be where people were.

But storytelling centered on these big cities doesn’t reflect the whole reality of experiences across the U.S. Take Minari, for example: Of all the places where the first Oscar-winning semi-autobiographical story of Korean Americans would take place, it might be easier to imagine New York City, Los Angeles, or San Francisco. But it was in rural Arkansas where the Yis, an ordinary farming family, lived. Oklahoma City was where they sent their son Jacob to get his heart defects checked. We are here in cities and towns big and small.

This made me realize there was a gap in news media: we needed a platform for a multitude of science stories beyond ethnic enclaves, to challenge normative experiences. The Xylom pivoted into doing in-depth journalism exploring the communities being shaped by and influencing science, including but not limited to Asian American groups. Like the patriarch David Yi, our team dug its own well — perhaps not as radical as his dismissal of county water, but similarly recognizing that there is something important in having ownership over how Asian Americans are portrayed and what our news media landscape looks like.

One of our very first news features, published in partnership with Science ATL, centered on a postdoc who was stranded in China for 443 days due to COVID lockdowns, unable to access her lab and her family stateside. Another reported essay looked into the vestiges of the caste system in STEM spaces in the U.S. Recently, we published a book excerpt about Kudzu and nativism from an Indonesian-Floridian environmental journalist.

We joined the Institute for Nonprofit News’ Rural News Network, publishing and contributing to syndicated rural stories, from toxic nuclear waste in Nevada’s deserts to wildfires in the Sierra Nevada and gun violence in rural Arkansas.

In the same vein, we cover neglected stories in Asia, and by extension the Global South, because our actions in the U.S. ripple across the seas, and impact our relatives and their neighbors back home, and vice versa. Earlier in the year, a National Press Foundation fellowship enabled Crystal Chow to delve into the dilemma of families with children who have the rare Angelman syndrome: What barriers must be overcome to ensure the accessibility of Western medical breakthroughs to families in need?

Editor-at-Large KC Cheng, a Taiwanese American based in Nairobi, Kenya, takes the lead on several of these stories. She talked with members of the Ogiek tribe in the Mau forest, whose land has been sold without their consent to an Emirati company while the Kenyan president receives fawning coverage from the legacy American press. She was also the first international reporter to document the impacts of the Mumbai Coastal Road, an eight-lane superhighway revived from a zombie idea from American planners in the sixties, finding that Indigenous fisheries have nearly been halved.

And we aren’t planning to just stop at one story about the Mumbai Coastal Road: Managing editor Agrawal and another Mumbai-based contributor will soon head back home to see what has changed since The Xylom’s initial reporting.

Having lived across continents, I know the U.S. is not quite exceptional in terms of both what it has to offer, or the atrocities it has committed domestically or overseas. It’s part of a tangled web between the home countries of those who come here, whose decision-makers and residents also have agency.

Internationalist, multilingual coverage that serves both Asian Americans and our relatives across the globe — by our count, The Xylom is the only American newsroom with science coverage in Nepali, Kannada, and Tagalog — is how we persevere to serve everyone affected by the issues we cover.

In late December, the CUNY Center for Community Media released the first-ever map and directory of media outlets run by and for Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities. Out of the 669 (and counting) newsrooms included, only one listed — The Xylom — focuses on science, environment, or climate reporting.

It can be lonely in this space, the same way Minari’s Jacob Yi notices that he just doesn’t look like anyone else at school. It’s not breaking news that marginalized communities rarely have adequate access to accurate, in-depth, nuanced science, health, and environment coverage. There are obvious logistical and funding model issues surrounding a small audience. There’s the constant need for more reporters, fact-checkers, and experts fluent in particular languages.

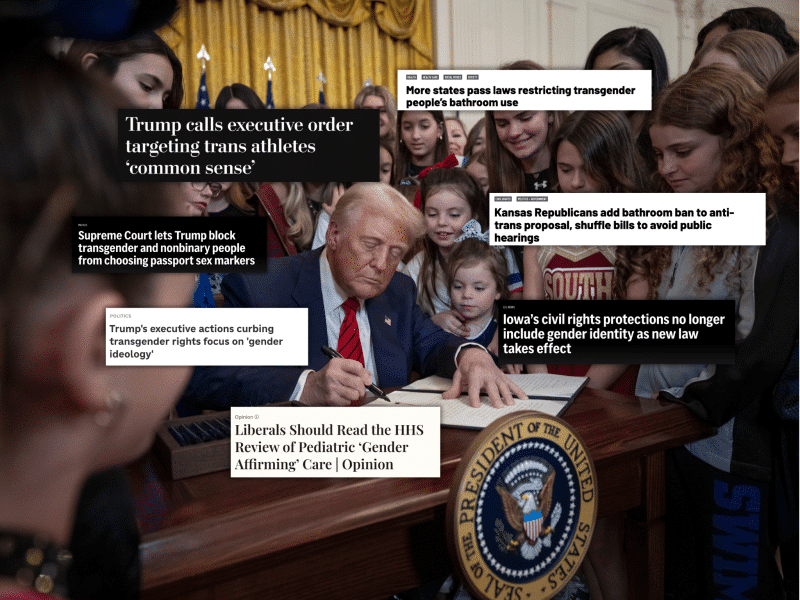

Even when there’ve been waves of coverage — the consequences of COVID-related stereotypes on Asian Americans, or how devastating climate change-induced wildfires, contamination, and destruction of sacred Native grounds in Hawaii conflict with the tourism, military, and research industries — some stories done by outsiders are well-meaning but ill-informed.

Some were out of touch. Some were downright malicious. The past few years have underscored even more how science issues affect Asian American communities, and more importantly, how media can cause secondary harm.

But as The Xylom progressed from a blog into a full-fledged newsroom, I realized that it doesn’t have to be that way. Reporting about stories that matter to our communities is our bias because we recognize the importance of understanding and being a part of the communities we cover. We are creating a niche that our readers (and soon-to-be readers) didn’t even know existed.

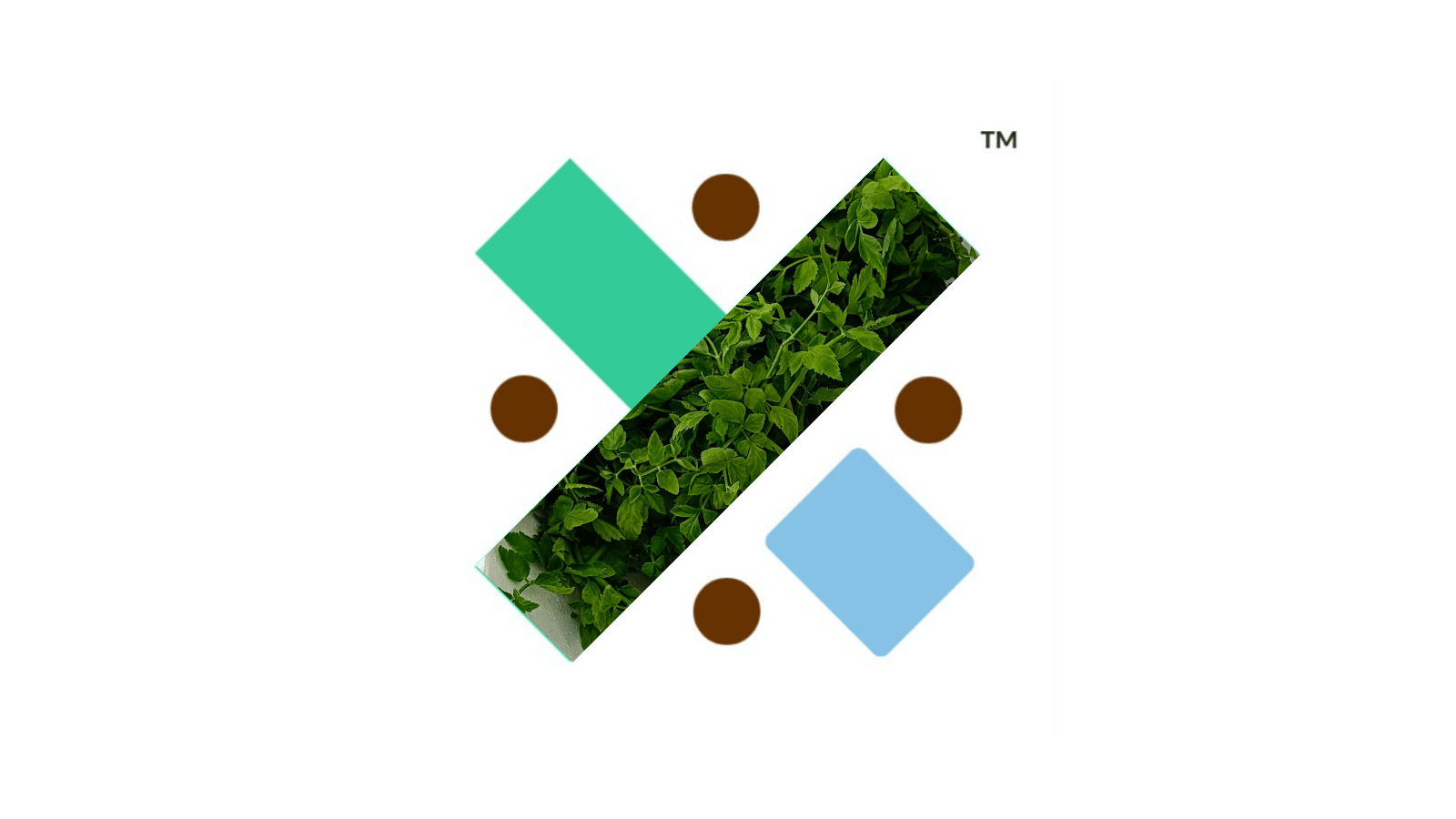

The Xylom celebrated our fifth anniversary last year. It was about time for us to refresh our branding. How could we distill our vision for culturally informed, community-focused, in-depth science journalism into one sentence?

I thought of minari, of how it finds a way to thrive and carry the diets and dreams of Asian Americans. I think of our name Xylom, itself derived from the Greek word xylon (ξύλον), the organ that transports water from the ground to the rest of the plant.

With that in mind, our new tagline couldn’t be more obvious: We grow science with words.

We know it’s hard work. The Yis could tell you all about the labor behind growth. But there’s nothing more rewarding than harvesting what we have grown, and joyfully sharing it with our community: Asian American science stories that provoke, inform, and inspire.

This story was edited by James Salanga. Copy edits by Gabe Schneider.

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Alex Ip is the founder and editor-in-chief of The Xylom.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director