Ta-Nehisi Coates: The Journalist

Systems are responsible for journalism’s failures, but so are the people that define them. In The Message, Coates doesn’t name them.

In The Message, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes about the stories that shaped his understanding of journalism and the stories that shape our world. He also comes to a conclusion that’s eluded too many journalists: Our biggest legacy media institutions and the language they use have failed us.

I first came to know Coates as an immature journalist looking for better words and a journalism job to take me away from my dorm. Between two-hour essay writing sprints in the early morning before class and a sporadic sleep schedule, I spent hours scribbling over a print-out of his Atlantic article, “The Case for Reparations”. I wanted to understand: What made his journalism compelling enough to warrant the reinvigoration of a national conversation about reparations? Was The Atlantic the place to learn about writing? And could I (should I?) follow in his footsteps?

The Message, instead of responding to my old curiosities — now sated by time and experience — reintroduced me to a writer who simultaneously believed in the power of his words and was humbled by them. The book, considering his accolades and experience, is Coates coming to terms with the challenge (and self-inflicted necessity) of building a more tenable world for journalists and the communities they cover – but I’m uncertain if his challenge to the institutions that raised him up is forceful enough.

In his haste to become a better writer, Coates internalized the language of white writers and adopted their same set of assumptions. “I thought I could stand apart, but looking back, I see the parts of my thinking that were most reinforced were those that dovetailed with those around me,” he writes. While making the case for reparations in 2014, Coates based his arguments on Germany’s reparations program to Israel without examining its exact implications for Jews and Palestinians.

He got it wrong, he says, because “there were no Palestinian writers or editors around me. But there were many writers, editors, and publishers who believed in the nobility of Zionism and had little regard for, or simply could not see, its victims.”

Despite all of this, he doesn’t name names: At a recent event in Los Angeles, when asked if he could have published the chapter on Palestine in The Message while he was at The Atlantic, Coates said it wouldn’t have been possible today. But when the interviewer pushed again to ask specifically about current Atlantic editor-in-chief Jeffrey Goldberg, Coates responded, “These critiques I have of media extend long past that. I don’t like the idea of putting it on a singular person — these are structures.”

It’s certainly a kind and careful approach, and I do believe the structures need to be dismantled, but I’m not sure it’s that simple. Institutions can be resilient, but they ultimately rely on norms defined by rules and rules defined by people. I believe Coates also knows this, because he acknowledges he learned from the writing of his peers with white supremacist beliefs, despite their moral failures.

“For much of my time as a journalist,” he writes, “I have been surrounded by people who, on some level, think of me as an exception that does not disprove their theories of white supremacy.”

In his review of the book, writer Jay Caspian Kang questions the gravity of closed-door decisions in mainstream newsrooms. He asks: “Do the hiring practices of a handful of élite outlets really measure up to the stakes and moral seriousness of the decades of conflict that Coates describes?”

This is a question where I think the answer is a resounding yes. Elite outlets, and those who operate them, have far too much agenda-setting power across the entire media ecosystem for what and who they publish to not matter.

As Coates writes: “When you are erased from the argument and purged from the narrative, you do not exist … the first duty of racism, sexism, homophobia, and so forth is the framing of who is human and who is not.”

Around the same time I started reading Coates, I read a book by another journalist: Goldberg. In the early 2000s, fresh out of advocating for the “profound morality” of the Iraq war, Goldberg published Prisoners, his experience serving as a prison guard for the Israeli army at Ketziot. Goldberg, a national correspondent for The Atlantic when “The Case for Reparations” came out, published a book critical of Israel’s army, but came hollow in its understanding of the people he kept in small boxes. This is who now leads a magazine with more than a century of history.

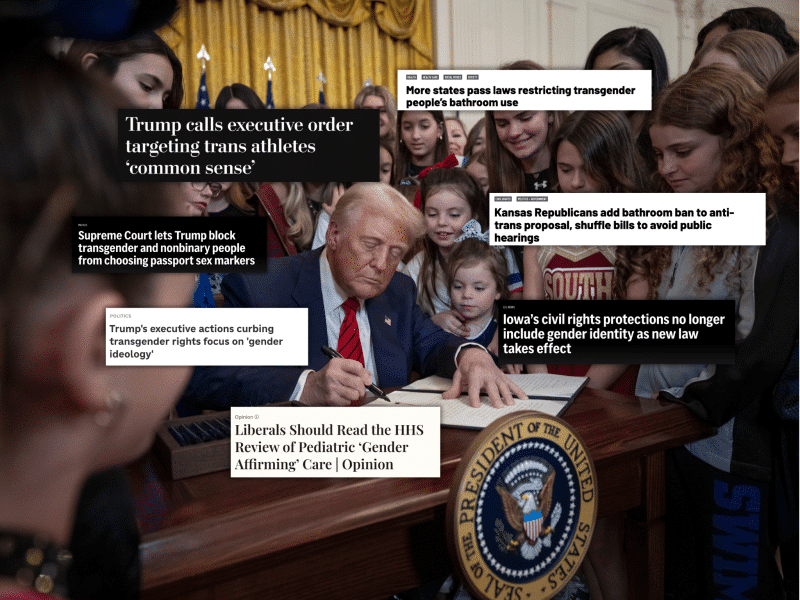

Coates is right to challenge the system, but I don’t believe you can avoid challenging the people who uphold it. There are specific people at varying degrees of fault for demonizing, for example, attempting to ban The 1619 Project or Coates’ book Between the World and Me: from school board members to 45th President. The same is true for those preventing the elevation of Palestinian journalists.

That’s not to say that specific people are irredeemable, but that they must be held accountable so that other voices can ascend. The stories we tell and the stories that institutions let people tell make a difference, or as Coates puts it in the book: “Journalism, history, and literature have a place in our flight to make a better world.”

A small portion of proceeds from book sales from this link go to The Objective. We’re a small non-profit newsroom: and every bit helps. You can also support our work here.

Among the experiences he chronicles is that of Deanna Othman, a Palestinian journalist who felt forced out of the industry after attending Medill Journalism School. It’s refreshing to see a journalist and teacher of Coates’ experience not only acknowledge he had never heard a perspective like Othman’s in the institutions he worked, but to understand just how critical it is that journalists like her be platformed. Solidarity should be an everyday occurrence — not a weakness, but a strength for journalists.

How often do we see a journalist reflect in public on their errors and complications? How often do we see them grow from them and uplift others? How often do we talk about these gaps in journalism within a national conversation on television and on morning shows and across the country?

“At some point the book tour will stop and I will stop talking … but the problem the book identifies, which is, the fact of Palestinian narrators being pushed out of the frame will remain,” Coates said in Los Angeles. “I will be in active conversation about what I can do that does not require me to be in front of the mic and make sure other people have the mic. That’s what I want.”

Coates draws from a wealth of writers to make clear how he learns to write and think about the world, but one struck me in particular — he cited a phrase the late Jamal Khashoggi, a journalist killed for his opinions by the Saudi government, was fond of: “Say your word, then leave.”

He writes this would be his preference, but that he also sees the problem with this kind of retreat: his words have real-world implications (in the case of this book, Coates follows a teacher who has to deal with his books being banned in their classroom).

The Message is, more than anything, about the stories people tell themselves to survive their own pain, failures, and impositions. It’s a book about how those stories and words matter — they define the way we see ourselves and they define how others see us too. This is the story Coates wants to tell about himself: that he, too, is still learning and that we should do the same.

I appreciate that Coates is choosing to think in public – how his words failed to hold up to his own standards and how he was harmed by and benefited from the profession of journalism.

Perhaps it’s not a fair burden for a writer who would rather let us hang on to his last word, but achieving what Coates writes he wants will require him to say more about the people – not just the institutions – that brought us here. I hope Coates forcefully continues to uplift Palestinian journalists and illuminate the failures that brought journalism’s institutions here. At the same time, there are too few established journalists with the moral clarity to offer this challenge and even fewer with the institutional authority and vocabulary to bring them to the forefront of the conversation.

I don’t believe Coates as an individual can change journalism alone, but I do know that systems are made up of people. I know that just like his understanding of words was shaped by other writers, so many young journalists (including myself) know that his words shaped ours. To see the world he wants to see, I believe it’s important for Coates to be specific: what is the purpose of his burden and moral clarity if it doesn’t extend to challenging the people who failed him and those he seeks to uplift?

While he’s no longer stationed with The Atlantic, he is part of a larger system that he has some power to help dismantle and reshape with his words and actions. He knows this.

“It is painful to admit that, because I’m part of it, because I believed in it,” he writes of the journalism lineage he is from. “And because I think the questioning, for me, has only just begun.”

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director