How to ensure reporting on ICE goes beyond focusing on citizenship status

Framing ICE coverage as a mere immigration issue may no longer meet the needs of the communities you cover, especially as many have weathered the fallout of raids, a new detention center, or surveillance tactics.

While in Chicago at NAHJ, I took seminars on using WhatsApp for community engagement, met John Quiñones, and sunbathed at Oak Street Beach. But over our happy hours and lunchtime plenaries, there was an air of tension. On the first day, at least a dozen Department of Homeland Security agents showed up unannounced at the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture in Humboldt Park — a neighborhood that is half Latine — and refused to show identification when pressed by museum workers to leave. Employees said they overheard agents discussing plans for the weekend’s Barrio Arts Festival, WTTW reported, which drew hundreds to the neighborhood for art, salsa lessons, and Latin jazz performances.

“This type of enforcement-style presence, particularly in a space dedicated to Puerto Rican culture,” NAHJ said in a statement, “raises serious questions about the targeting of Hispanic communities.”

Puerto Ricans have been U.S. citizens since 1917, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Jones-Shafroth Act that granted island natives citizenship through an act of Congress.

So a big question many at NAHJ also asked: Does focusing on citizenship even matter anymore?

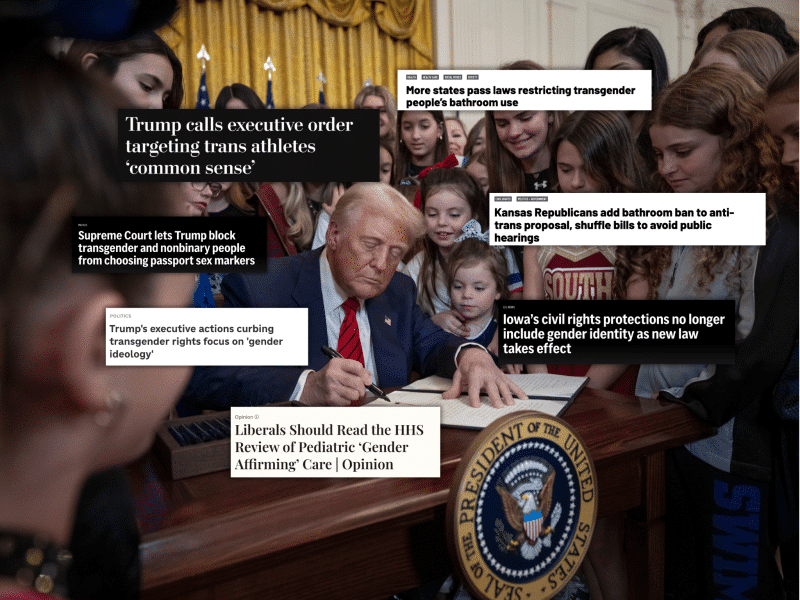

Since the Trump administration ramped up ICE raids in January, ICE agents have repeatedly and illegally detained non-white U.S. citizens at work and during traffic stops because they “look” like immigrants.

They tried to raid a Puerto Rican restaurant in Philly without a warrant. Soon after, the Navajo Nation told NBC News they received reports of tribal members — U.S. citizens — being questioned by ICE agents based on their appearance. Watering down repeat instances of racial profiling and free speech suppression as problems that just impact those with a certain legal status presupposes that ICE operates in a vacuum, not the reality that their tactics are creating a pathway for other law enforcement agencies to do the exact same.

Framing ICE coverage as a mere immigration issue may no longer meet the needs of the communities you cover, especially as many have weathered the fallout of raids, a new detention center, or surveillance tactics.

Even as a young journalist, I recall sitting in on newsroom meetings about if it was permissible to call a racist act — well — racist and thinking about how our hesitation would shape the historical record, making it seem as though racism was something that was up for interpretation, something that could be debated and argued and downplayed. And in reading immigration coverage, I see that same dance around decisiveness, about whether we have the authority to call something racial profiling or unconstitutional.

Often, the final editorial decisions are not up to reporters, who are also trying their hardest to serve immigrant communities without diluting their coverage. So, how can you cover ICE in a context that isn’t just limited to immigration?

Here are some helpful frames:

- Get specific about tactics: There’s enough reporting to know that at least some of ICE’s tactics involve racial profiling, or questioning people based on their skin color. A judge just banned the agency from doing so in California. But if your newsroom isn’t at a place where you can use that language without hedging, be specific and descriptive. Note if an agent asked about ethnicity, and try to incorporate video footage or eyewitness accounts to rebuild interactions — instead of relying on statements from government officials — to demonstrate that there is a level of trust and consensus around what happened.

- Incorporate historical context: When in the past has the U.S. government used national security concerns as a reason to detain or surveil communities of color? The Trump administration is often described as “unprecedented,” but finding parallels between their tactics and those of prior administrations can provide perspective. Plus, historical reporting can help you diversify your sources to include archivists, professors, and social history researchers outside of the same cadre of immigration organizers and attorneys.

- Case in point: The FBI famously spent millions of dollars to build dossiers on thousands of Puerto Ricans based on even an inkling of suspicion that they were part of an independence movement. At one point on the island, it was illegal to fly the Puerto Rican flag — details that are particularly salient in the context of ICE targeting a major Puerto Rican cultural institution.

- Find patterns in the negative space: I know this is a big ask in a frenetic news cycle, but if you have the time, it could be worthwhile to examine commonalities among communities that ICE has yet to target, as well as the long-term consequences of immigrants receding from certain aspects of public life. We know some immigrants have begun to cut church, the doctor, or even school out of lives over fear, but what could that mean down the line about who in the U.S. can safely access economic mobility, good health, or civic life?

Beatrice Forman is a Philadelphia-based reporter who also writes a biweekly column focused on pro-democracy reporting for The Objective’s newsletter, The Front Page. She previously worked as the coordinator for Democracy Day.

This story was edited by James Salanga.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director