Journalism as a public good has always been an exception

Misdiagnosing journalism’s collapse means we’ve been mourning a myth and ignoring the radical legacy — and future — of people-powered media.

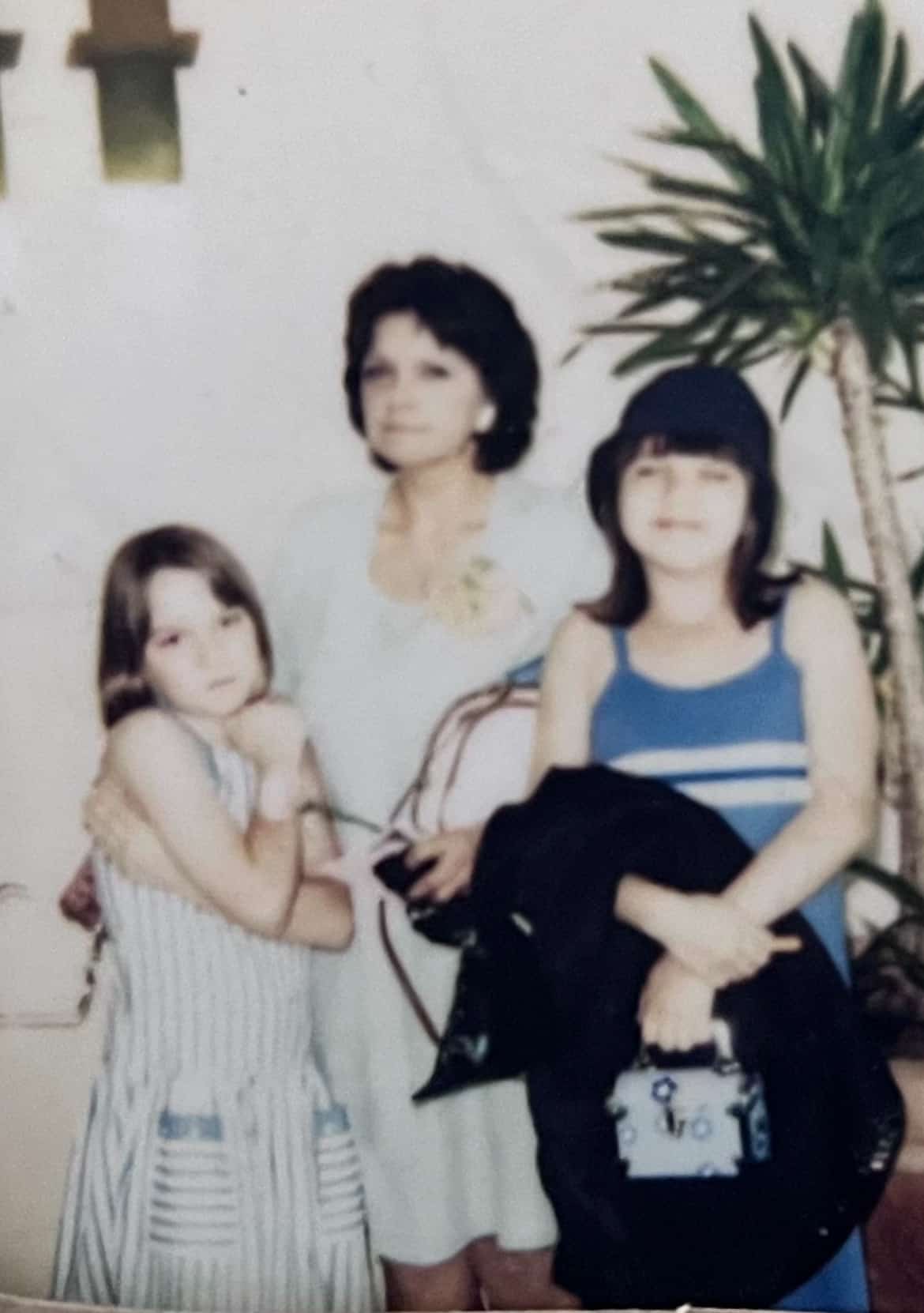

When I was 12, I pored over a handwritten Mother’s Day essay competition response, explaining why my mom was the greatest. Home was not the safest place growing up, so I wanted to give my mother an epic gift to soothe the layers of pain. I read the piece aloud to my mother before I submitted it to my 6th grade teacher. I don’t remember what I wrote, I just remember we cried the whole time I read it.

I won the competition. The first place certificate now hangs framed next to my mother’s bed where she lays every day, losing the battle to metastatic stage four lung cancer. And the emotional response around our kitchen table, a site of unpredictable struggle and unpredictable nourishment, opened something up inside of me. A fearful, thrilling thought bubbled to the surface — I wanted to be a writer. By 18, I tempered my author ambitions, but not my hero child ones, by deciding to bootstrap myself and my family out of the working poor class.

The happy medium was to pursue a stable, more lucrative career in journalism. (You can laugh with me.)

My upbringing pulled me towards journalism and also guided me along the way to try to make work that could equip people to disrupt the status quo, not to uphold it. But after nearly 20 years in journalism, I left the industry — though I still advocate for the transformative, relationship-building storytelling possible outside of newsroom walls. What made me the most weary about journalism was the lack of material change it produced for the communities I cared about the most, for people like my mother.

To paraphrase my brilliant former Memphis-based colleague Wendi C. Thomas, I was also tired of people asking the wrong questions and celebrating the wrong wins. I’ve realized youth media, libraries, and neighborhood organizing are places where the power of storytelling has the most impact. Those are the halls of journalism whose survival I’m most rooting for.

I believe that what we’ve called the “death of journalism” is actually a return to its origins: propaganda tools for wealthy businessmen to shape public opinion in service of their interests. The radical idea — that journalism could be a public good rooted in education and accountability — has always been the exception. If we want media that actually serves the people, radical organizers like Assata Shakur have identified the problem: We need to build it ourselves, from the ground up, as part of our community, labor, and organizing infrastructure.

Ironically or fatefully, I graduated from journalism school in 2009, during one of the industry’s bleakest moments with print newsrooms losing more than 24,500 jobs between September 2008 to September 2009. The blessing of learning to be resourceful at a young age, combined with little faith in obtaining a traditional reporter job, was that I got to spend my career in journalism in more “fringe” community-centered organizations — from hyperlocal news and youth media to eventually co-founding or co-stewarding experimental models to transform news sharing. We lost this plot and history because of the promise of a free, open worldwide web. I’m prayerful that this political climate can help us revive these practices.

Journalism in the U.S. has long been dominated by wealthy elites, from Hearst or Pulitzer of the 19th century to today’s billionaires like Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos. The idea of a free and independent press has been aspirational more than actual. As retired comms/journalism professor Gerald J. Baldasty frames in his piece The Nineteenth-Century Origins of American Journalism, there’s instead been a longstanding tension between those who see the media-as-business versus those who see it safeguarding “democracy and liberties.” The former dominate the landscape.

Media-as-business has won the noise war in our democracy rooted in consumption and the protection of corporations. Conservative philanthropy and individual donors have been giving far longer to the media and, on the whole, far outgive “progressive” foundations. And the roots of U.S. journalism are far more propagandistic than we’ve been taught or we remember. Pre-Civil War, Baldasty writes, “the vast majority of American newspapers were highly political in content.”

“Cities and towns such as Boston or Worcester were served by newspapers representing each of the major parties in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts of that day,” he continues. “Indeed, newspapers were the very symbol of partisan activity in that era.”

This hyper-partisanism gave way to the Hearst and Pulitzer era of journalism, where sensationalism at scale, also known as yellow journalism, influenced the public’s reaction to international affairs like the Spanish American War.

But former Black Panther, Black Liberation Army member, and political prisoner Assata Shakur’s 1998 prescient open letter to the media highlights a counterbalance to this era: the legacy of the Black press and progressive media. As she notes, journalism that safeguards democracy and liberties was created by those pushed to the margins. Shakur called on newsrooms to create media “to educate our people and our children and not annihilate their minds.”

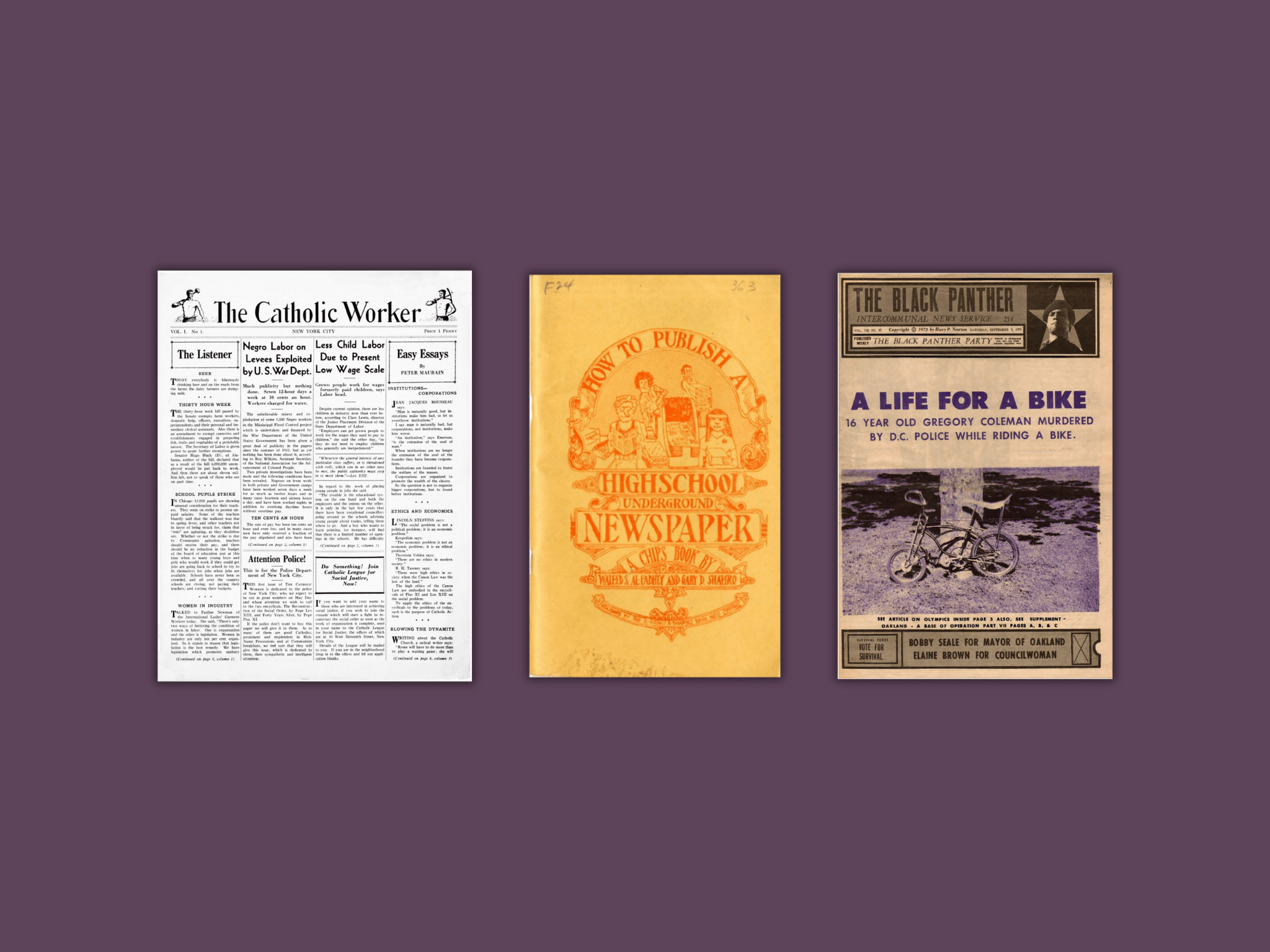

From Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s The Free Speech and Headlight newspapers, to The Catholic Worker, to the Black Panther Party newspaper, and to worker-produced media like Grace Lee Boggs and Jimmy Boggs’ papers, we have always had people-powered models of journalism that actually functioned as the fourth estate. Their purpose wasn’t to exist in perpetuity, but instead to connect readers to action to change their material conditions. These examples are just the tip of the iceberg modeling media rooted in justice and solidarity.

The lineage of people-powered independent outlets is vast. At their heart, these outlets were incredibly practical, like the newsletters that were produced by public housing residents of the Jane Addams apartments. On a recent tour I took of the National Public Housing Museum in Chicago, a guide pointed out the reprinted building newsletter, where folks advertised upcoming events or their small businesses. Some expansive independent publishers like the New England Free Press, which ran from 1967 to 1981, exemplify the movement media end of the spectrum. Their 1970 “How to Publish a High School Underground Newspaper” reads like a timely roadmap for more than student publishing.

Unlike the priority of clicks in today’s media business, these outlets or presses were rooted in connection — reaching your neighbor, your coworker, instead of casting a wide net. They also weren’t about having a journalism degree from a four-year institution to produce public information. (Side note: The first graduate program in journalism was established by Columbia University in 1912, endowed by Joseph Pulitzer.)

There was a brief moment when the digital era opened up space for journalism to become a true public good, but platforms were quickly captured by capital. The promise of accessible, participatory media was short-lived under the control of private owners. The fallacy of wider loops of connection have shifted the emphasis to information that entertains.

But of course, there remain voices breaking through the mainstream noise — including citizen journalists during the Arab Spring in late 2010 and the exposure of the genocide in Gaza — and organizations (like the Dissenters) that are trying to weave the Internet’s capabilities into the fabric of longstanding community media-based organizing.

These efforts are innovative and deeply relevant. One such memorable effort I witnessed was in 2010, when teaching youth media at Radio Arte, a now-defunct program of the National Museum of Mexican Art. Five years later, I tried to steward the lessons from Radio Arte with the co-founding of City Bureau, a journalism lab based on Chicago’s South Side.

During this time, I was on the receiving end of the philanthropic trend to support local news, as the business model of yesterday continues to die. This was a moment in my life where I realized that money can’t, nor should it, fix everything. I put to rest two ideas — that I could save my family if I’d just made enough money and that heavily-resourced outlets could be the most transformative.

Nothing affirmed the above reflections more than when, in 2020, I moved to Tennessee for divinity school and started working for the Memphis-based newsroom MLK50: Justice Through Journalism and serving as board co-chair of liberatory outlet Scalawag Magazine. South of the Mason-Dixon Line, I saw how grassroots media better equips people to fight disinformation, build power, and care for each other. Learning the distinctly Southern ways this kind of transformative journalism can develop outside of a newsroom while also studying spiritual organizing ultimately affirmed my decision to exit journalism.

As a media-based organizer, though, I’m still wrestling with questions about how to shift media towards material change and what it means to practice community media in today’s shifting religious and worker landscapes.

With fewer unions and more atomized, remote labor, what would it take to revive a culture of collectively produced, worker-held information? What would it mean to see newsletters, zines, podcasts, and prayer circles not just as outlets, but as infrastructure — tools for survival, strategy, and spirit? I believe media that builds power needs relationship, memory, and a politic of care more than it needs mass distribution.

Andrea Faye Hart is a queer radical Quaker and media-based organizer who believes Chicago is the center of the universe.

This story was edited by James Salanga. Copy edits by Jen Ramos Eisen.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director