Without New Voices legislation, we risk igniting an epidemic of silence among U.S. student journalists

Defunding and devaluing public media is a top-down erosion of truth-telling that undercuts efforts to strengthen student press freedom and contributes to censorship of student journalists.

This story was co-published with Shift Press.

Over two months ago, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting closed after President Donald Trump signed nationwide funding cuts to public media into law, threatening rural communities’ access to information and working journalists’ jobs. This devaluation of public media and journalism reveals itself to be a top-down erosion of truth-telling that silences student journalists.

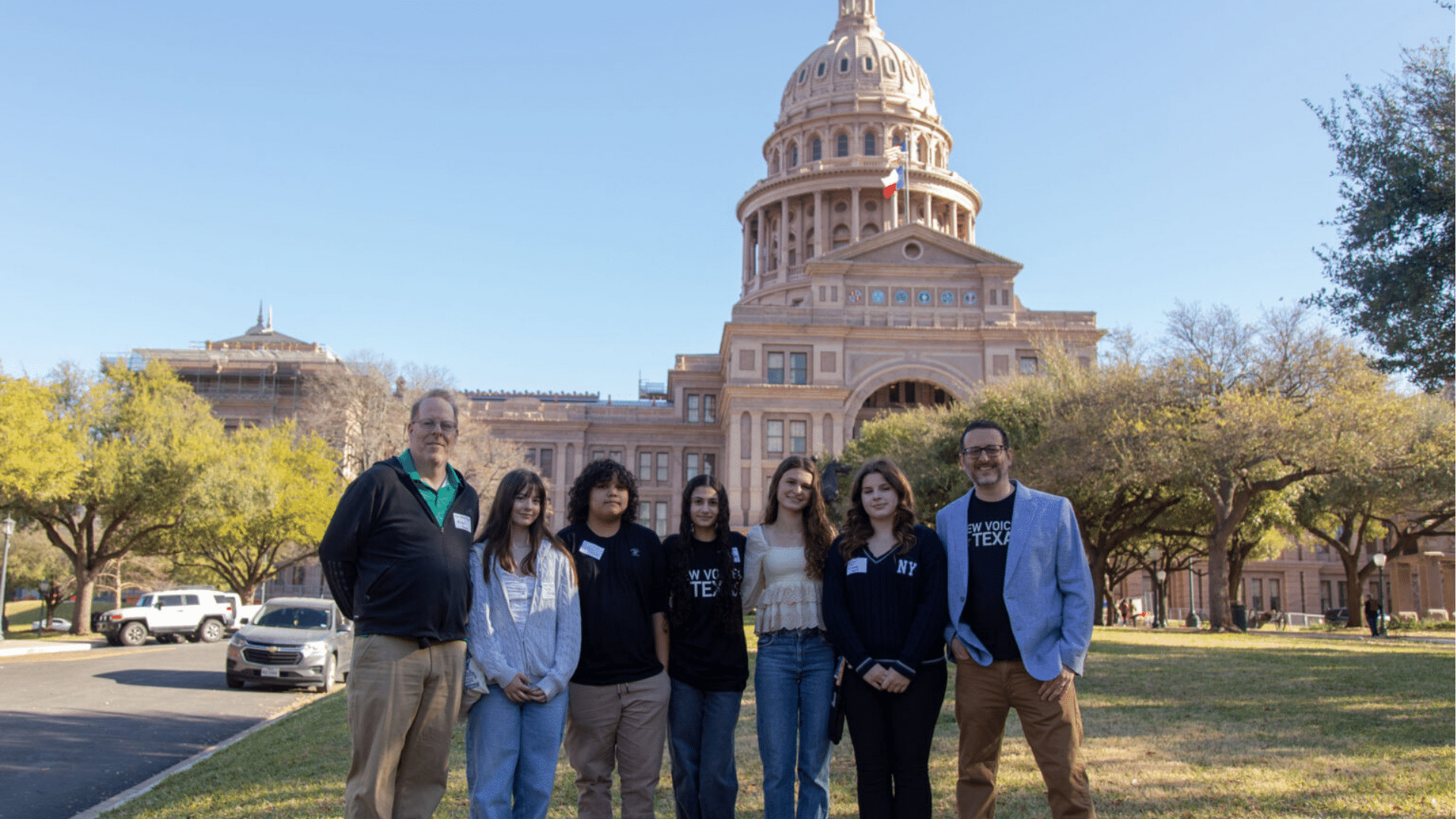

It also undermines the New Voices movement. The student journalist-led, nonpartisan, and grassroots legislative effort has worked to strengthen student press freedom since 2015.

“Defunding public media sets the precedent for defunding student media,” said Pratika Katiyar, a former student journalist and an activist working in privacy at the American Civil Liberties Union. “It empowers high schools and colleges that maybe won’t agree with their students’ reporting to censor them. It gives them more leverage to violate student press freedom rights.”

The rights of student journalists are protected by the First Amendment through the 1969 case Tinker v. Des Moines. But a 1988 court decision set the precedent that public school officials could censor student speech in school-sponsored activities if they had “legitimate pedagogical concerns”— a vague phrase that has long concerned student journalists due to potential misuse by school administrators.

The New Voices laws created by the Student Press Law Center, a legal organization responsible for defending and advancing the free press rights of student journalists, help clarify this precedent. They include protections for the free expression rights of student journalists, limiting the kind of content that can be censored.

As politicians and administrators see national attacks on the media as justified due to the recent defunding, they’re more likely to justify silencing student journalists, too. So student journalists like Faith Zantua, co-news editor at her school’s newspaper The Spoke, say it’s important to build coalitions for the New Voices movement to protect student journalists’ rights.

“Doing this New Voices work is setting a precedent,” said Zantua, also the student lead advocate of New Voices Pennsylvania. “That’s one of the most important things that this legislation does. It exists to establish this precedent that not only is student journalism important and something we should care about, but it’s also something that deserves protection.”

Censoring journalism impacts student journalism and the pipeline into newsrooms

Zantua and Katiyar have both dealt with censorship in their high school reporting careers.

As a freshman, Zantua and her editorial board were told by her principal that they could not publish a senior map spread they had run for years. That motivated Zantua and her fellow editors to send a letter to the principal, with the support of the Student Press Law Center (SPLC) and the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), which ultimately resulted in the spread’s publication.

When Katiyar was a high school journalist, an article she wrote related to her high school’s admissions process jumpstarted a Washington Post investigation. It also prompted her to start working with the Student Press Law Center and New Voices in Virginia.

“Through the process of reporting that work, and other stories, there were instances where we weren’t being as open as we wanted to be,” she said. “Like [in] many stories around reputation, I realized across the country, this kind of self-censorship or censorship thing was going on.”

Censoring student media also impacts local news coverage.

As the number of local newsrooms in the U.S. has continued to shrink, student journalists have stepped up to provide coverage in areas termed news deserts. In some rural communities, public media outlets may be the only primary source of information. Likewise, college and high school newspapers sometimes serve as the sole functioning media covering a local community.

However, such responsibility can come with its challenges.

Related: Student journalists just want their credit

“It’s an incredible opportunity for a 16-17-year-old reporter to have [their] byline on something that everybody sees at such a young age,” said Mike Hiestand, senior legal counsel of the Student Press Law Center. “But … there’s a reason we call them student journalists. [They] are learning the craft, what works, and what doesn’t work in terms of putting out our good-quality journalism. Just thrusting and pushing them out there to have to do sorts of reporting comes with risks, particularly if they’re not really well-supported.”

Public media outlets — especially local NPR member stations — serve local, under-reported, and marginalized voices. Reducing their funding chips away at the press as the cornerstone of democracy while signaling that local communities are not valued.

Censorship of journalists has existed before the current administration. But attacks on the news media under Trump’s second presidency are a dangerous civics lesson to the next generation about a free press’s importance to democracy.

“The president has called the media the enemy of the people,” Hiestand said. “This has an impact, and the long-standing principle of a free and independent, robust press is very much threatened right now, and student media are clearly part of the mix.”

Unlike corporate outlets, which often reflect the priorities of owners or advertisers, public media and student media hold themselves to similar standards of independent reporting — despite some legislators targeting public media as “overly biased.” Such outlets are often supported by community donations, individual memberships, and student fees.

“There’s a lot to think about when it comes to public media versus privately owned media,” Katiyar said. “It’s a case study of editorial independence.”

Zantua says that as a student journalist, it’s been discouraging to watch public media and journalism at large be discredited by the current administration.

“I grew up reading these articles, and this was the standard in a lot of student journalists’ minds of what we want to achieve with our writing,” Zantua said.

Over the years, NPR and PBS member stations have been a landing place for student journalists to receive their first internship opportunity or first job, offering them training, mentorship, and publication opportunities.

When public media is defunded and this pipeline shrinks, it sends a chilling message that truth-telling without corporate influence is not worth supporting. Student journalists doing what they’ve been taught to do — questioning and holding power accountable — hear the same message when their stories are censored by administrators. Together, these actions signal to school administration and lawmakers that a healthy press is no longer a civic priority.

This creates a top-down trickle of censorship that starts from national outlets, which slowly seeps into school newsrooms, where administrators can control or even smother student voices.

Student journalism is an antidote to voicelessness in the face of censorship and feeling unable to acknowledge perspectives and truths that matter. It has given me and so many other youth the space to create work for themselves and their communities, even during incredibly difficult times.

I’ve spent this past year experiencing incidents of censorship as a high school journalist, while battling personal health challenges. Working on New Voices has kept me grounded and connected to journalism as I was fighting against censorship that student journalists across the nation face in my state.

In my weakest moments, I felt like my body and the world had broken me. But fighting to ensure student journalism — this art and act of truth-telling — continued, reminded me that my voice matters, that we can fight this plague of student voicelessness.

To support student journalism, New Voices chapters need support now

Student journalists will continue to carry a target on their backs until New Voices laws are enacted. Currently, 18 states have passed New Voices legislation, while coalitions in the remaining 32 continue to fight strenuously to ensure it gets implemented within their state policies.

Legislators must see protecting the press, whether that be professional or student journalists, as a democratic priority. But when those same lawmakers are actively defunding or discrediting national media outlets, it becomes harder to persuade them as they evaluate the vitality of student press freedom right now.

So it’s time young people recognize the power they have and can start to take advantage of the speech tools that exist while building coalitions with other journalists — students and professionals — who support press freedom.

“We need to hear from young new voices now more than ever,” Hiestand said. “I don’t think a lot of young people understand the power that they truly have … Student media [has] a huge role to play in pushing back and creating the world they want.”

Zantua also sees hope in the rising New Voices movement.

“There’s been a rise in people recognizing that it’s important we protect journalism,” Zantua said. “For New Voices PA, we’ve actually seen a lot more movement than we have in years, and I personally think it’s been fueled by all of the attention on journalism.”

Getting involved with New Voices is one of the most tangible policy actions you can take to set up a better future and a more independent press in your state. If you feel powerless in the face of public media defunding, know that there is an avenue of change waiting for you. These laws provide protections that allow journalists the freedom to report without fear of censorship, offering not just relief, but a foundation for a more informed future.

To get involved, start by seeing if there’s an existing New Voices coalition in your state. If not, the SPLC’s Advocacy and Organizing Team can help you start one. If forming a coalition is not possible, contacting legislators is a way to highlight the importance of these laws for both student journalists and the communities they serve.

Another way to plug in is by understanding student media protections at both the state and your local high school district level is crucial. Check local school districts’ policy handbooks for guidelines on school-sponsored media. If protections don’t exist, rally support to implement a student press-freedom friendly policy using SPLC’s district model policy.

If the platforms that nurture truth-telling and accountability weaken, if student journalists lose support, what happens to the next generation of voices? What happens to kids who, like me, need journalism to survive, to feel human, to feel heart?

That is why the defunding of public media worries me and why New Voices legislation matters.

We risk igniting an epidemic of voicelessness across the nation without it.

Poojasai Kona is a high school journalist and a New Voices Texas North Texas regional organizer.

This story was edited by James Salanga. Copy edits by the Shift Press team.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director