The local news contract is broken. Civic media can fix it

Darryl Holliday on how City Bureau’s Documenters’ program models the new social contract needed for local news and the civic media system emerging today.

This piece is part of our Civic Media Series. Read the Civic Media Magazine and explore pieces from the series here.

“I didn’t know I could go to government meetings.”

I think about this phrase often, though I’ve heard people say versions of it many times since then. The first time was from a Documenter, a community member trained and paid to attend public meetings on behalf of civic media organizations across the country. He was a 31-year-old educator and organizer from the South Side of Chicago — someone who kept up with current events and local news. In that moment, waiting outside of Chicago’s police headquarters for the monthly police board meeting to begin, he wasn’t saying, “I don’t know where to find information about this meeting.” He was saying, “I don’t know how to exercise my power as a citizen here.”

It shows where we as journalists have failed in our attempts to hold public officials accountable, by making our readers feel like they don’t have the power to do it themselves. But it also exemplifies why the public needs a new covenant with the institution we know as “the press.”

Social contracts are implicit agreements within society that enable people to cooperate for social benefits. Most often you see the concept in the creation of the state, when individuals come together and cede some of their individual rights so a representative government can make decisions on behalf of the public good.

In journalism, the implied agreement is that journalists provide information to the public and hold powerful people accountable, while society grants the press freedom of expression and the right to operate. It paints the general public as passive recipients, while journalists wield the valuable civic skills of investigation and storytelling. Our argument has been: We’ll handle being the watchdog, as long as you pay us with attention and advertising.

Now, that economic model is broken. Meanwhile, society has changed; the world has grown far more technologically complex, government bureaucracy has proliferated, and corporate malfeasance has become more insidious. Powerful people can simply invent narratives and “facts” rather than respond to serious charges of misconduct. To say that journalists alone can hold the powerful to account is not just hubristic, it’s factually incorrect.

A new local news contract will acknowledge the vastly different world in which we operate. It will insist that journalism skills are civic skills that everyone should have, seeking to reintegrate them into society as quickly and broadly as possible. It will remind citizens of their power (and responsibility) to join journalists in the work of keeping our communities informed, engaged, and equipped to tackle the challenges ahead. In other words, this local news contract will forge a new, stronger partnership between journalists and the public — and clarify why journalism must not only continue, but evolve, to meet the challenges we face today.

In 2016, as co-executive director of City Bureau, I led the development of the Documenters Network and launched its web platform Documenters.org in 2019. Rooted in my experience as a neighborhood reporter in Chicago, the program was designed to permanently solve a problem I saw in communities across the city as I attended public meetings hosted by governmental offices like the City Council, the Police Board, the Board of Education, and the dozens of sub-committees, advisory councils, and task forces that make up Chicago’s city and county governments. The problem? As local newsrooms declined over the years, coverage of these crucial governmental processes — where members of the public interface directly with elected officials who deliberate and vote on impactful local issues — were some of the first beats to be cut. As information about these civic processes declined, so did public engagement around them. Today, it’s not uncommon for public meetings to be completely unattended by both reporters and residents.

As co-founder and national impact director of the civic journalism lab based in Chicago, home of the Documenters Network, my solution was simple: train and pay residents to work in collaboration with journalists to ensure public meetings are attended and covered.

Today, there are over two dozen Documenters sites across the country. Thousands of people have been trained to report on tens of thousands of public meetings and other assignments in a variety of mediums. More than $1.15 million has been paid out to the people most impacted by the decisions made at public meetings. In the process, Documenters have built a new public record and a new kind of community, rooted in the production and sharing of high-quality, verifiable information that otherwise wouldn’t leave the halls of power.

By basing our work in participatory practices, prioritizing relationships across lines of difference, and ensuring that the people in our program were proximate to the communities we served, Documenters modeled the new social contract that I believe is needed in this new era of local news.

Documenters is far from alone in this effort. After nearly 20 years in the news industry as a beat reporter, editor, producer, investigative journalist, and nonprofit newsroom founder, I’ve seen many of my peers vacillate between their own energy and ambition to repair the news ecosystem and their discontent with the industry. That’s because this approach to media, what we are calling civic media, sometimes requires a 180-degree shift in values and behavior.

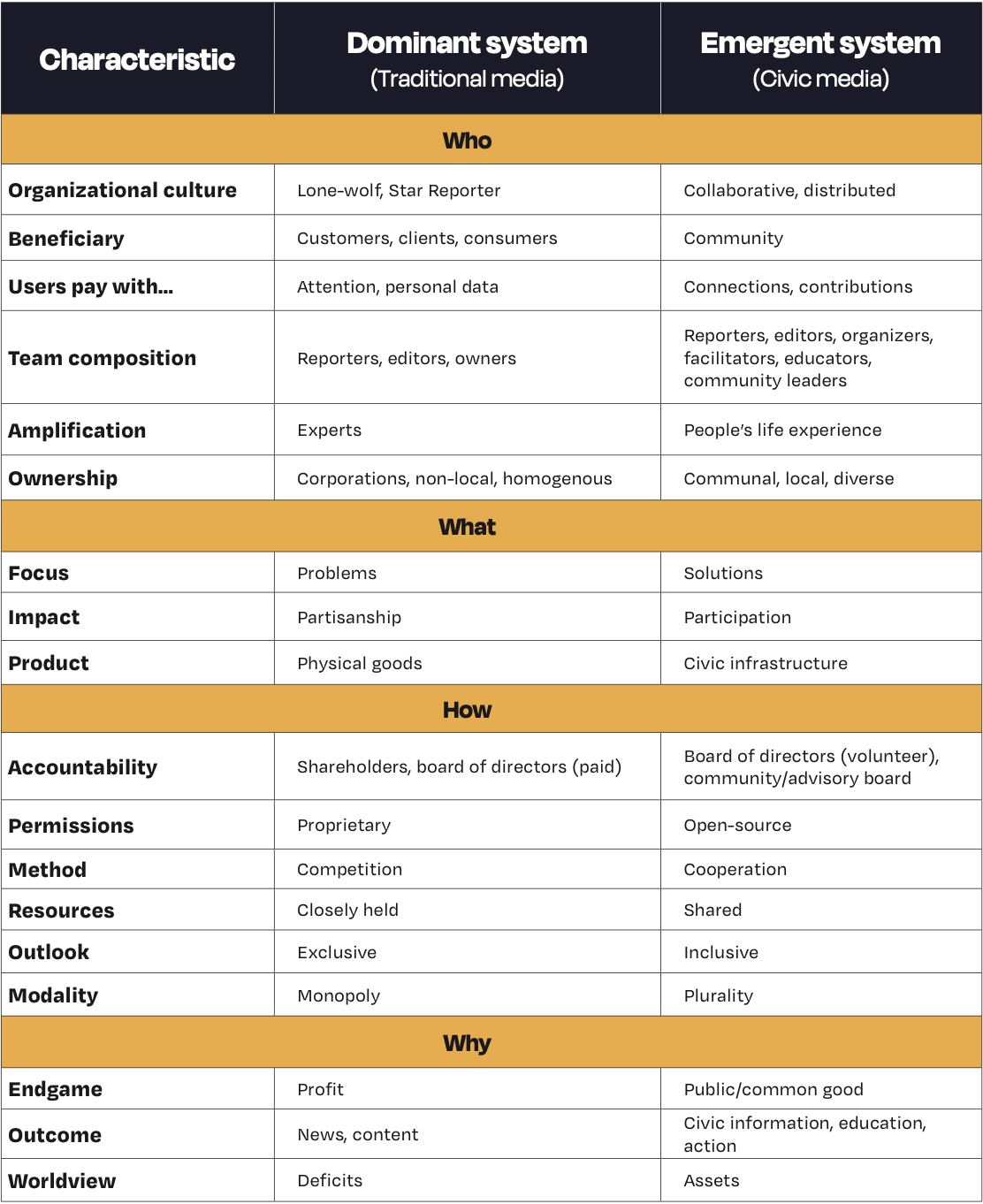

Civic media practitioners aim to be collaborative and coordinated in an environment that prizes “lone-wolf” star reporters. They aim to serve communities, not just customers and consumers. They find that the skillsets of traditional journalism are limiting, so they aim to be facilitators, conveners, and organizers of information.

These are not reporters who want to simply “cover an event,” they want to use their journalism skills to help get people to the event, develop and lead workshops at the event, and help event organizers connect event outcomes to other assets in the community. While civic media practitioners have faced headwinds for decades, often labeled too idealistic, too niche, overly sensitive, or pollyannaish, in recent years we have seen them gain traction across the industry. Many of them are featured authors in this magazine. In them, I see an “emergent system” that uses news and information to build local relationships and creates pathways for public participation in the newsgathering process.

At a larger scale, philanthropic efforts like Press Forward are working to organize funder networks around civic media values like centering community information needs and prioritizing transformation of existing news infrastructure, bringing philanthropy into deeper dialogue on the elements of a new local news contract. Public policy wins like New Jersey’s Civic Information Consortium are finding new ways to center civic information through support for prosocial news and information outlets, reintroducing the role of government in the preservation of a fair, independent, and people-powered press. At the same time, new media alliances, like News Futures, are being forged that are bridging innovation in civic engagement and leadership with decades of community media infrastructure (think public access/PEG media, public media, and civic media), honoring and expanding a tradition of participatory media in the United States.

The new contract between journalists and citizens will position journalism not as a separate entity serving the public, but as an act of citizenship itself. Of course, it won’t be a literal document to be amended and passed by a commission. It will live at the local level where people engage directly with local newsrooms and community information sources, where it will be constantly renegotiated and recommitted by generations of community members. It will look like people writing letters to the editor, supporting local news that improves their quality of life, committing acts of journalism where they live, and a myriad of broader pathways into civic life that they will create, together. The question is not whether the demand exists, but whether local newsrooms will evolve to meet the community where it is, rather than where they generate the most profit.

Only then can the media ecosystem move beyond disruption toward restoration, renewing its fundamental purpose as a public good. Our democracy will be stronger for it.

Darryl Holliday is a journalist, community steward, and civic strategist. He’s a co-founder of the Pulitzer Prize-winning civic newsroom City Bureau and currently runs Commoner Company, a consultancy focused on making civic life more accessible. He’s a recognized leader in participatory media and local news, an Ashoka Fellow, and co-author of the “Roadmap for Local News.”

This piece was edited by Bettina Chang. Copy edits by James Salanga. Fact-checking by Bashirah Mack.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director