How disaster reporting hit home for two Appalachian journalists after Helene

Disaster journalism is vital, but can be traumatizing for both journalists and sources. We can make it better by treating disaster survivors — and ourselves — with more humanity.

One year after Hurricane Helene, a catastrophic storm which killed hundreds of people and left thousands more wading through infrastructural collapse, journalists descended on Appalachia for commemorative events and feature stories.

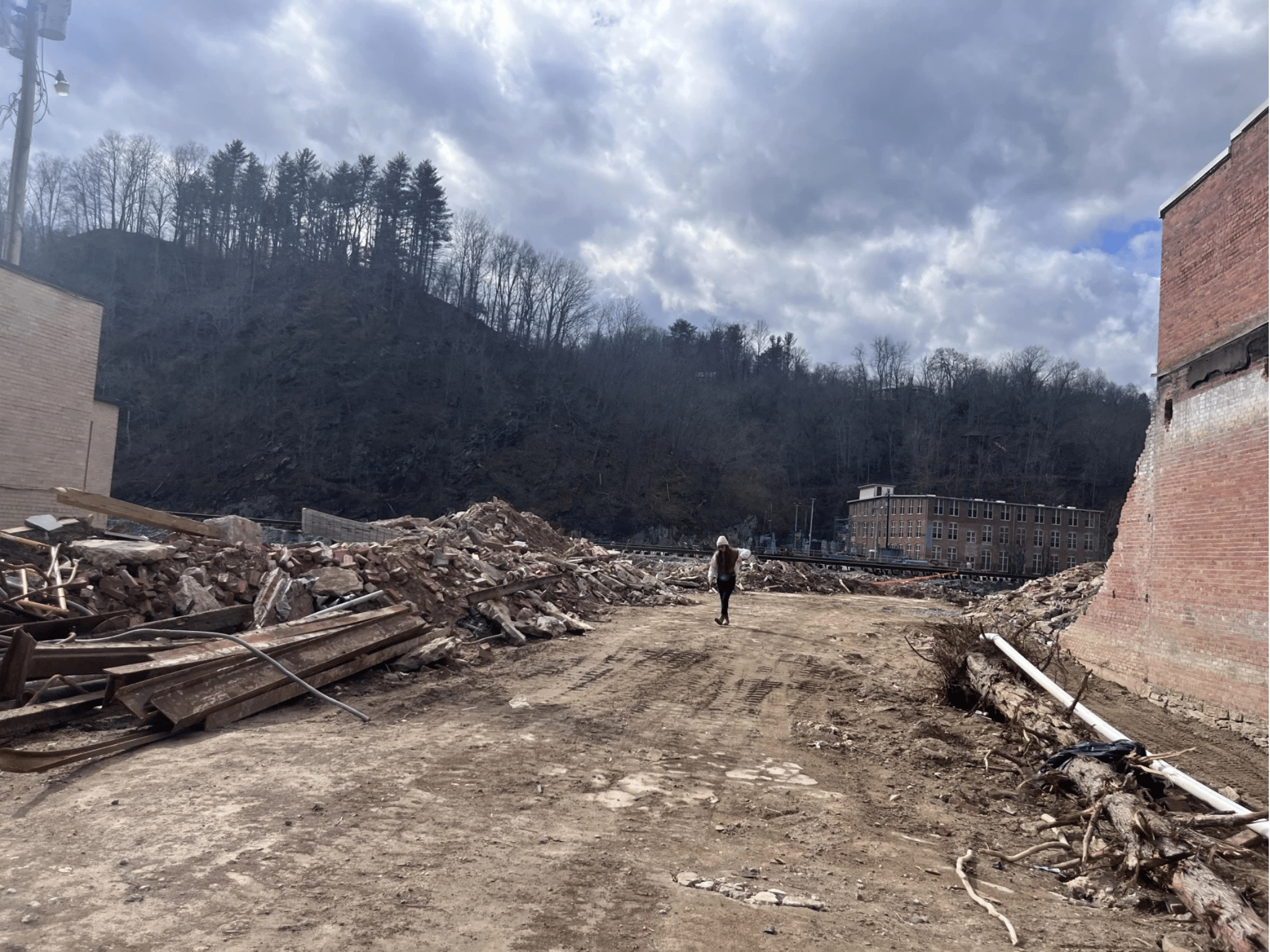

They came from all over, looking to show the world what it was like to live through Helene, and the devastation it left behind. On the anniversary, as they did a year ago, photographers, broadcasters, and writers drove over broken roads and past muddy riverbanks to capture communities in enduring crises. Afterwards, most of them moved on to other stories, or continued to follow from afar. For us, though, it was personal, and we remained.

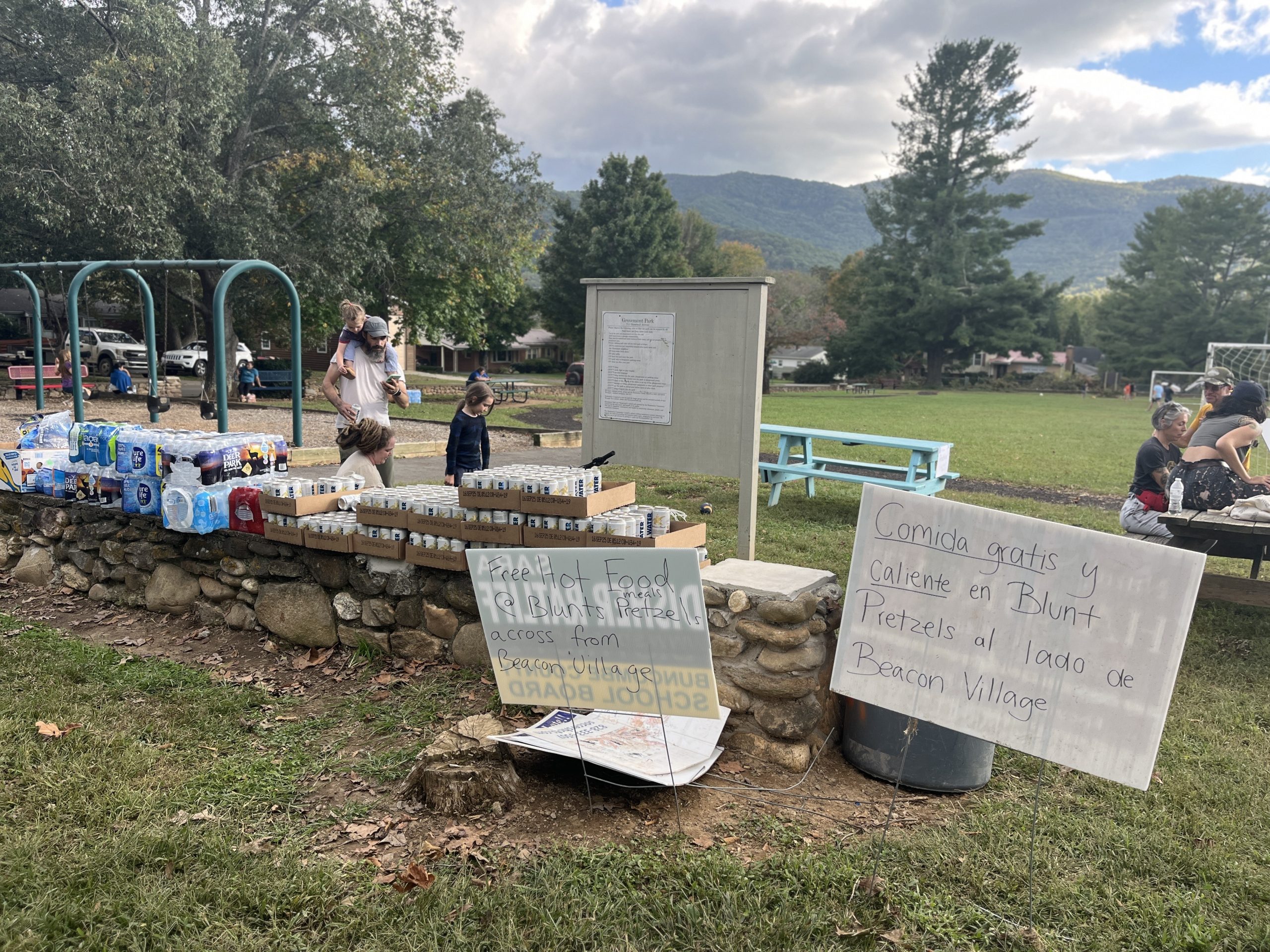

We are two reporters at Blue Ridge Public Radio who lived and reported through the initial storm in September 2024 alongside an incredible team. At a time where communication blackouts were widespread, people turned to the radio. Suddenly, hundreds of thousands in our area were listening to our around-the-clock storm coverage, focused on immediate needs — like where to find food, water, medicine and shelter. We helped people understand how to apply for FEMA and drove hundreds of miles to collect live and largely unedited interviews with storm survivors.

Over this past year and a half, we’ve seen again and again how disasters become spectacles. They pop into the news cycle with attention-grabbing photographs of destruction. Journalists are charged with authentically depicting the true hardship people are going through. We push ourselves to seek the most intense scenes, wring tears from people, and sometimes even join them in their living rooms. The pressure of keeping the public’s attention changes us as journalists and as humans.

And it feels gross to say, but our careers might not be the same if it weren’t for disaster. After years of sporadic accolades, Blue Ridge Public Radio went home with multiple national awards in a year. As individual journalists, we’ve gotten awards, exposure, and opportunities for national media hits even while grappling with our own trauma from the event.

This relationship to tragedy and survivors is complicated, and we’re still reckoning with it.

What we do know is that for so many, Helene was the worst moment of their lives. Disaster strips people of their dignity, but we don’t have to be a part of that. Whether interfacing with an EMS provider, someone who lost their home, or even another community journalist, we can remember to never treat our sources like a means to an end.

Disaster reporting doesn’t always benefit survivors

I, Laura, find myself thinking often about a moment with a cab driver who happened to be a Katrina survivor. This fall, I was in New Orleans for a journalism conference during the 20-year anniversary of the storm. After learning I was in town for the conference, the driver stiffened a little.

He was remembering the frustration he felt with some of the Katrina anniversary fanfare. One reporter, he recalled, pressured him to divulge his memories from the disaster, pressing for traumatic details. He was torn — he wanted to be welcoming and accommodating, but he also felt uncomfortable and used.

It’s a story familiar to many survivors. In the wake of disaster, people have cameras pushed in their face not just by reporters, but also by influencers and well-meaning charities.

All of the above are trying to bear witness and help in their own way. For some, like the owners of flooded businesses or community organizations needing to raise awareness of their work, attention can be a boon. Or it can be just cathartic to tell the story.

But often, it’s unclear how giving an interview will directly benefit any individual disaster survivor. After being part of the story ourselves, and knowing how exhausting this performance of tragedy and trauma can be, we’ve wrestled with what we’re asking of people when we ask them to rehash stories about Helene.

Images of poverty and a long Appalachian history

This is my (Katie’s) second major disaster, my first being the deadly 2022 Kentucky floods, and I’ve seen the way the disaster news cycle plays out.

I don’t want to be jaded, but I often felt that in order to draw attention to the situation, I had to find the most desperate scenarios, depict the most suffering I possibly could, and push my way into people’s lives to do so. In lower moments, I think about Susan Sontag’s essay on depictions of human suffering, “Regarding the Pain of Others.“

As Sontag writes, “The image as shock and the image as cliche are two aspects of the same presence.” I didn’t want to play into that dynamic.

Sontag’s essay is about war photography, but in some ways, it applies to disaster coverage. When we document disasters, we are exposing the public to the realities of suffering, but in the pursuit of a good story, our work can end up reductive. Sometimes it can deprive people of their dignity, especially in historically cash-poor places like parts of Appalachia, as in the controversial and famous CBS special report “Christmas in Appalachia,” which used footage of impoverished families to boost sympathy for the region while playing into stereotypes.

In Helene’s aftermath, those words reverberated as I found myself retreading old territory. I reported, or saw others report, the same exact stories from 2022: FEMA is coming, apply, apply, apply; the governor is visiting saying we will not be forgotten. Sometimes all I could see was what Ta-Nehisi Coates called “the gruel of misery,” the facelessness that tragedy gives to its victims.

A complicated commemoration

The anniversary of Helene resurfaced many of these feelings and questions, as reporters, including us, revisited storm-battered towns, and outlets republished old pictures of destruction alongside newer ones of “repair.” As many people around us chose to mark the year after disaster through art, community meals, and gatherings in restored community spaces, bars and restaurants, the sober and sometimes self-congratulatory tone of the media made a jarring contrast.

We found ourselves wondering: Was it necessary to reopen old wounds? We tried to reconnect with sources from a year ago, and while some wanted to chat, others avoided us. In the immediate aftermath, we knew what people needed was food and water, but what did people need now?

It’s easy to feel cynical, even despairing, when climate change is driving such increasingly destructive disasters. This storm almost certainly won’t be our last; to serve our communities well, we need to fight this cynicism at every moment, to retain our humanity and empathy in this work.

Disasters are inherently chaotic, and when you’re in the muck of it all, it can be difficult to find, or even look for, a blueprint. But there’s certainly opportunity for us as journalists to approach this work with an open mind and a sense of respect for the dignity of disaster-impacted communities. Before disaster strikes, it’s possible to look to the many others innovating and reshaping what disaster journalism can be.

In rural Alaska, when a typhoon threatened the Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta, KYUK broadcast lifesaving alerts in English and Yugtun. In the wake of catastrophic floods, VT Digger took climate accountability reporting to a whole new level. On the national level, we’ve admired ProPublica’s accountability work post-Helene, and their collaboration with The Assembly, a statewide outlet that delivers that impactful reporting to local inboxes while pointing a way towards future solutions and ways to keep people safer.

And during times of doubt, we encourage you to find ways to better understand your community. Get to know disaster survivors as subjects and active agents in their own survival, not just as helpless victims.

Our coverage spanned training for the next disaster, but we also found the people who are writing albums, organizing primal screams on bridges, planting tulips, learning how to serve Spanish speakers, and picking up trash from the river.

As reporters, there’s an opportunity to do so much more than highlight misery. We can learn what neighbors are capable of when the grid, when running water, when transportation all fail — and how people with power can prepare our infrastructure. We can learn how to portray disaster-impacted communities in the whole of their humanity, while serving them with the information they really need and want the next time disaster strikes home.

Laura Hackett is a multimedia journalist based in Asheville, North Carolina. She is the Hurricane Helene Recovery Reporter for Blue Ridge Public Radio and has also produced stories for NPR, Marketplace, Grist and The Associated Press.

Katie Myers is a reporter, audio producer, and playwright in the mountain South. She writes about climate change in Appalachia for Blue Ridge Public Radio and Grist. She previously served as a climate solutions fellow at Grist, and as an economic transition reporter in eastern Kentucky with the Ohio Valley ReSource and WMMT 88.7 FM.

This story was edited by James Salanga. Copy edits by Marlee Baldridge.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director