Reckoning with the Federal Communications Commission’s history of structural racism

Since the agency’s inception, FCC policies have undermined the 14th Amendment rights of Black people and Black communities.

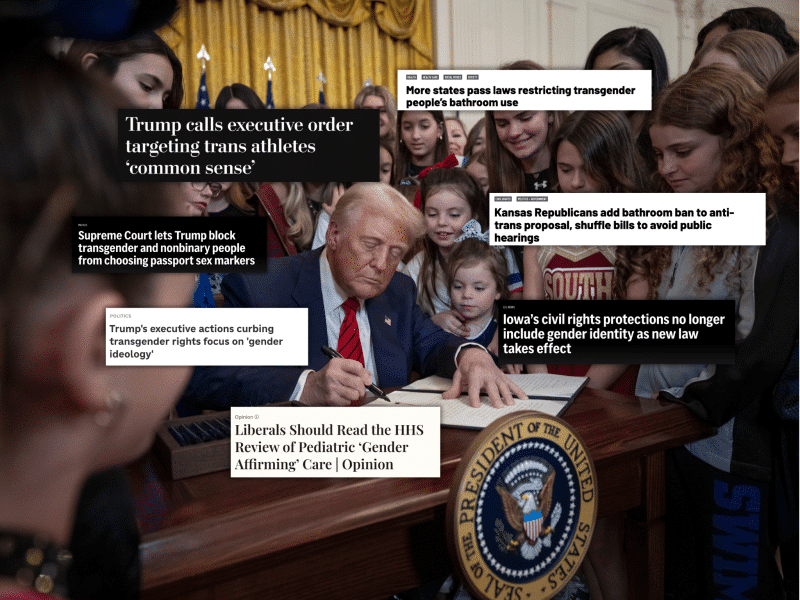

Since taking office, President Donald Trump has escalated his attacks on powerful media companies as a critical part of his effort to rapidly usher in an authoritarian regime.

So far, Trump has signed 170 executive orders that attempt to strip the civil-rights protections of Black, Latine, and other historically marginalized groups. This includes ending the federal government’s diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs and the use of disparate-impact liability to enforce civil rights laws.

Sherrilyn Ifill, the founding director of the 14th Amendment Center for Law & Democracy at Howard University School of Law, wrote earlier this year that “the sheer volume of Trump’s actions targeted at programs and policies designed to advance the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equality and full citizenship for Black people is staggering.”

Starting on Inauguration Day, Trump moved swiftly to dismantle historic civil rights protections and further undermine the equal protection rights of Black people and other historically marginalized communities. The New York Times Magazine’s Nikole Hannah-Jones wrote that Trump is “systematically taking apart the enforcement apparatus of the federal government, agency by agency … sending a powerful message to American institutions that discrimination will not be punished.”

And now, the U.S. Supreme Court’s conservative majority has granted the president with greater executive powers that could allow his administration to move forward with an executive order that would strip the 14th Amendment’s birthright citizenship of children born in certain parts of the country to parents who are not citizens.

As a co-creator of Media 2070, a media reparations project, we have continued to document the history of anti-Black racism in the media system from colonial times to the present to understand how both media policies and media institutions have historically served the goals of protecting our nation’s racial hierarchies. Powerful white-owned and -controlled media institutions have also continued to create and distribute racist narratives that criminalize Black people and other communities of color, shaping the cultural conditions for the adoption of policies that reinforce racial subjugation.

Brendan Carr, Trump’s loyalist appointee to head the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), is placing greater regulatory pressure on the president’s media targets as Trump calls for ending government funding of NPR and PBS. Carr, who authored a chapter in Project 2025, is investigating the DEI programs of several companies, including Disney and Comcast, calling their policies “invidious forms of DEI discrimination.” Verizon ended its DEI programs to win FCC approval of its merger with Frontier.

Related: You don’t mean DEI

A critical factor those fighting for racial justice and against authoritarianism have to contend with in understanding Trump’s political rise is the powerful role that federal agencies like the FCC have historically played in contributing to undermining the 14th Amendment and historic civil rights protections.

Anti-Black racism has been embedded within the commission’s DNA since its founding, despite the Black community’s long struggle to ensure the public airwaves serve their informational needs.

Broadcast regulations reinforce racial apartheid

The FCC was founded nearly a century ago to regulate the emergence of commercial broadcasting.

The constitutional rights won by Black people during Reconstruction with the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments ended chattel slavery, granted Black people citizenship and equal protection rights, and codified Black men’s right to vote.

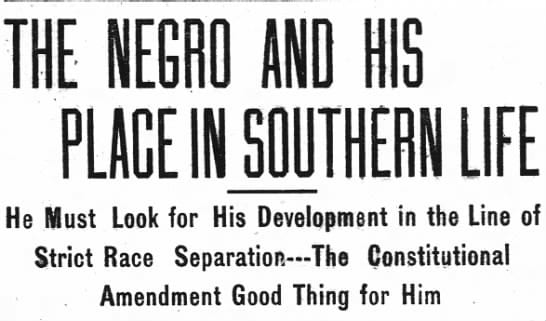

But powerful white politicians, whose racist beliefs were informed by the deadly backlash to Reconstruction, shaped the regulation of this new industry during a period that historian Rayford Logan called “the nadir” in race relations.

During the nadir, Hannah-Jones wrote in her New York Times Magazine piece, “the rights that Black Americans achieved following slavery’s demise were violently and systematically taken away” with “the blessing of the federal government.”

It was during this period the federal government ushered in a powerful new media system that reinforced racial apartheid in government policies and in our society.

World War I served as a catalyst for the Woodrow Wilson administration’s investment in the development of radio technology. This effort was led by Josephus Daniels, the Secretary of the U.S. Navy and a devout white supremacist.

Following the war, Daniels pressured Congress to nationalize radio to prevent foreign ownership of our nation’s radio infrastructure. But Congress rebuffed his effort. The Wilson administration instead worked with General Electric to create the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), also known as the Radio Trust, in 1919. That collaboration ensured the powerful U.S. companies would exercise dominant control of our nation’s emerging broadcasting industry.

While Daniels played a critical role in radio’s development, he was also a powerful newspaper owner. He called the Raleigh News & Observer, which he owned, “the militant voice of white supremacy.” In 1898, Daniels used his paper to help orchestrate a deadly coup in Wilmington, N.C. that overthrew the city’s multi-racial government.

Even before assuming office, Wilson, whose father enslaved Black people, openly loathed Reconstruction due to the emergence of Black political power.

He celebrated Reconstruction’s end, since he viewed it as restoring “the natural, inevitable ascendancy of the whites, the responsible class.” Upon taking office, he segregated the federal government and embraced the reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan. In 1915, Wilson hosted the first-ever film screening at the White House: The Birth of a Nation, one of the most racist films in cinema history.

Following the war, Wilson’s Justice Department investigated the Black press and authored a report in 1919 in an effort to convince Congress to pass peacetime sedition laws. The report outlined a number of issues that drew the department’s ire, including that the Black press “more openly expressed demand for social equality.”

FCC and its precursor steeped in segregation

For the majority of the 1920s, Herbert Hoover served as the secretary of the Commerce Department before becoming president in 1929. Hoover’s commitment to racial segregation applied to both city zoning and the public airwaves, where his agency’s policies benefited big companies such as RCA.

Hoover and his Commerce Department led an effort to increase white home ownership through exclusionary zoning that prevented Black people from owning homes in the same neighborhood. A 1923 Commerce Department publication “promoted ethnic and racial homogeneity by urging potential home buyers to consider the ‘general type of people living in the neighborhood’ before making a purchase,” author Richard Rothstein mentions in The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Government Segregated America.

Hoover’s Commerce Department also oversaw the licensing of radio stations during the emergence of this new communications sector and “routinely assigned amateurs and low-power stations the least desirable frequencies.”

In 1927, Congress created the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), a precursor to the FCC, to regulate the radio industry. The new commission allowed commercial broadcasters, such as CBS and NBC, to consolidate control over the country’s most desirable and powerful radio channels.

And shortly after the FRC’s formation, the government also awarded a radio license in 1927 to the Independent Publishing Company, publisher of the newspaper The Fellowship Forum — an organ of the Ku Klux Klan. The Commerce Department, still run by Hoover, had flagged the group’s application for a license due to its anti-Catholic bigotry, not its racism. The company, nevertheless, received a license to serve the Washington, D.C., and Virginia areas, and that station, under different ownership, today broadcasts as WTOP Radio.

Not a single Black person or Black-owned company received a broadcast license from the FRC.

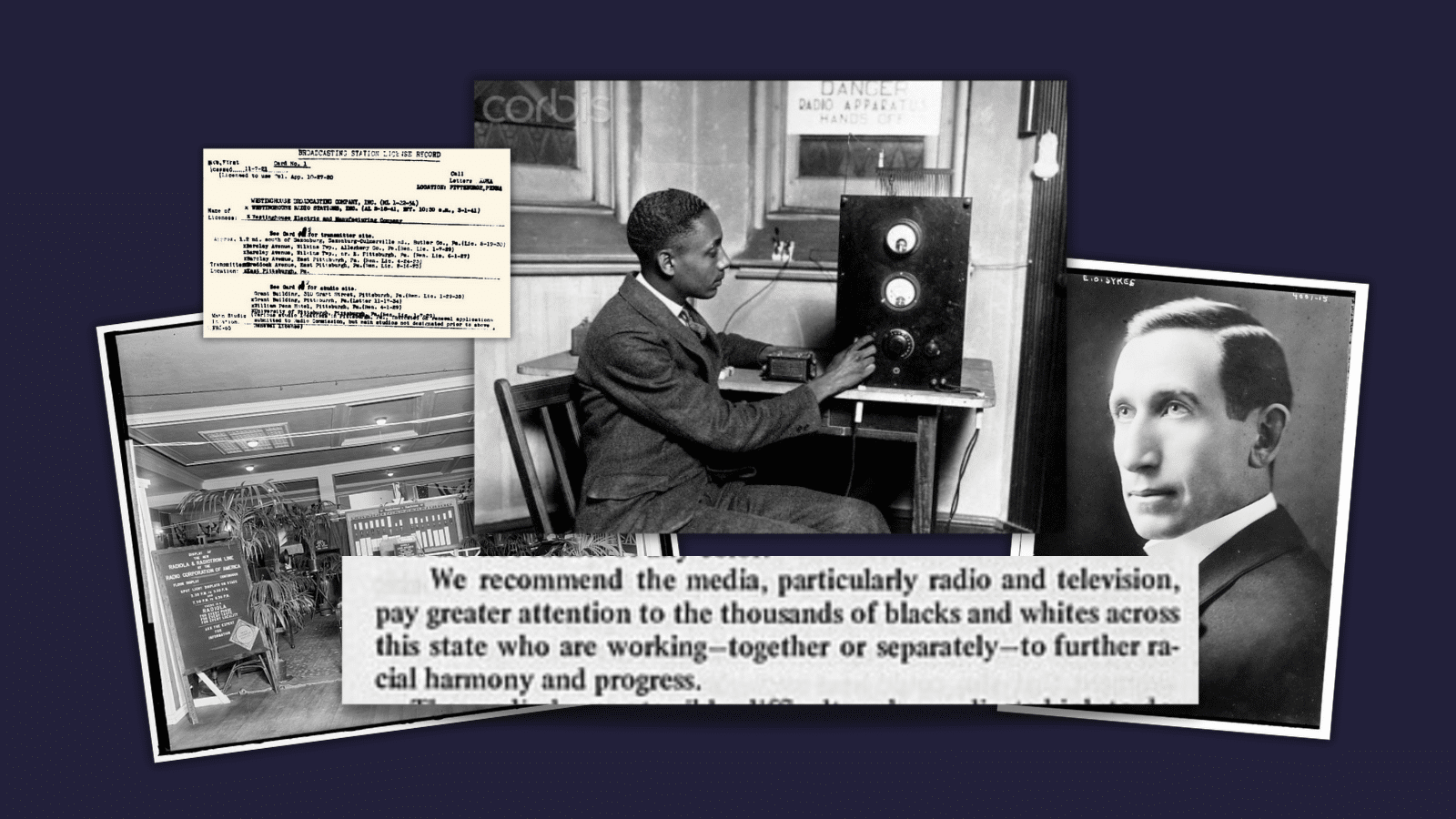

But it wasn’t for the community’s lack of interest. Rufus P. Turner, the first Black person to receive a broadcast license in 1925 prior to the FRC’s founding, operated a low-power station in Washington, D.C. He was still a teenager. The Pittsburgh Courier published an article on Jan. 9, 1926 with a bolded, large-type headline that ran across the top of the page: “First Colored Radio Broadcasting Station Installed.”

The same year the FRC was founded, the Pittsburgh Courier sponsored the first radio program devoted to “Negro journalism” that aired on WGBS in New York City. The Detroit Independent, a weekly Black newspaper, wrote about the importance of Black radio ownership: “As a race, we can not tell our story to the world over white men’s radio stations, any more than through the white press. If we want to reach the ears of the public, we must do it by means of the Negro press and Negro radio stations.”

Despite the embrace of radio by many in the community, the FRC denied the Kansas City American, a Black newspaper, an application for a radio station license.

As broadcasting grew, the Federal Communications Commission was founded in 1934 to serve the public interest and regulate broadcasting as an extension of the FRC’s mission. During its early years, the FCC continued the FRC’s pattern: It didn’t award a single broadcast license to a Black applicant or Black-owned business, let alone any other people of color.

It took until 1949 for Jesse B. Blayton Sr., an Atlanta businessman, to become the first Black owner of a radio station in the United States. This was more than two decades after the FRC’s creation.

The first FCC chairman, Eugene O. Sykes, embodied the agency’s failure to consider the public interest of Black communities. Sykes, who had served as the FRC’s last chairman, received the support of racist South segregationist Democrats to head the new agency.

Sykes, born in Mississippi in 1876 at the end of Reconstruction, served on the Mississippi Supreme Court from 1916 until 1924. He was appointed by Gov. Theodore Bilbo, whom the Equal Justice Initiative has described as “a towering figure among white supremacist and segregationist politicians.” During Sykes’ tenure, the court decided consequential cases on race, such as Moreau v. Grandich, which prevented a family from sending their four children to public school since it believed the children’s great-grandmother was Black.

Since its inception, the FCC awarded licenses to many white-owned and -controlled broadcast companies that profited off of segregation and allowed segregationists access to the airwaves to oppose integration and equal protection rights of the Black community.

Hate on the airwaves

We do not have a complete history of the role broadcast stations played in granting access to segregationists and hate groups seeking to use the public airwaves to prevent and undermine equal protection rights of the Black community.

United Church of Christ Minister Dr. Everett C. Parker once asked the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. how he could help the civil rights struggle. King’s response was: “Can you do something about the TV stations in the South?”

Since King’s comment, our nation has yet to reckon with — or undertake a full accounting of — the number of broadcasting companies that profited off of segregation. Yet we do know some facts. For instance, the FCC approved a merger between ABC and United Paramount Theatres in 1953, even though Paramount owned and operated segregated movie theatres at the time.

Author Stephanie R. Rolph wrote in her book that the White Citizens’ Council, a hate group seeking to protect segregation, created a TV program in 1957 — Citizens’ Council Forum — that originally aired on WLBT-TV, the NBC affiliate, in Jackson, Mississippi. The Council soon moved the weekly TV and radio programs to Washington, D.C., to attract more powerful congressional members’ appearances, and even managed to use the congressional studios to record the show.

The Council created the TV program, she noted, because it “feared that on radio and television, and in movie theaters, the acclimation to integration was slowly wearing down the commitment to segregation.”

In 1964, the United Church of Christ’s Office of Communication filed a license challenge against WLBT-TV, arguing the broadcaster had failed to serve the city’s Black community, including covering controversial issues regarding race. The station’s general manager was a member of the White Citizens’ Council who once complained to NBC “about certain programs promoting social equality and intermarriage of whites and Negroes.”

The FCC denied the petition, stating that the challengers did not have legal standing. But the public scored an historic victory in 1966, when a federal court’s decision favored the church and local Jackson activists — it established citizens’ legal standing to challenge a broadcast license and to make sure their voices were heard on FCC issues.

Even after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the federal government remained aware that our nation’s news media were resistant to integration.

Then-U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach “believed the country” was “still segregated, now illegally, in nearly all schools and employment sectors, including in the news media and government itself,” author Taylor Branch wrote.

The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders — also known as the Kerner Commission — released a report in 1968 that examined the root causes of 1967 uprisings. The report stated the media had “contributed to the Black-white schism in this country” and that the white press “repeatedly, if unconsciously, reflects the biases, the paternalism, the indifference of white America.”

And in its 1969 report, the Community Relations Service, an agency with the Department of Justice, stated: “Few American institutions have so completely excluded minority group members from influence and control as have the news media. This failure is reflected by general insensitivity and indifference and is verified by ownership, management, and employment statistics.”

Meanwhile, the FCC’s general counsel, Henry Geller, sent a letter to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in 1969 that asked Hoover to share names, addresses, and birth dates of people suspected of being “members of either various Klan organizations or the Minutemen organization” who used radio equipment — some of whom “were said to be Commission licensees.”

Geller also sent the same letter to J. Walter Yeagley, Justice Department’s assistant attorney general and director of the internal security division.

We do not know the FBI’s or the Justice Department’s response to this letter, or if the licensees Geller referred to were actually operating broadcast stations. But we deserve to.

Redress the history of harm

We must grapple with how the nation’s media policies and its media institutions have contributed to undermining the 14th Amendment rights of the Black community and other historically marginalized communities.

As Mark Lloyd, the former FCC associate general counsel, has noted: “National and local communications ecologies suffer from the vestiges of Jim Crow, a structural racism that harms not only people of color but all Americans.”

Since our founding in 2020, the Media 2070 project has called for redressing the history of anti-Black harm caused by our nation’s media institutions and media policies. We have continued to document this history to provide more clarity and context on the role that our media system has continued to play in upholding and protecting racial hierarchy.

Related: A newsstand that serves the information needs of Black communities

The public should also know the extent that the government agencies, like the FCC, have known and allowed broadcast stations, and our nation’s communications infrastructure, to be controlled by groups or individuals advancing a segregationist agenda.

The media companies currently surrendering to Trump’s racist attacks — and the suggestion that the presence of people of color working for these institutions or efforts to produce more programming serving communities of color is somehow illegal — are just the latest examples in a long history of government-sanctioned discrimination that has eroded equal protection rights.

But our nation’s failure to redress this history is a central factor in Trump’s political rise, our country’s descent to authoritarianism, and the U.S. government’s continued passage of systemically racist policies.

Joseph Torres is the senior advisor for reparative policy and programs at Free Press and a co-creator of the Media 2070 project. Joseph is also the co-author of the New York Times bestseller News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media with Juan González.

This essay included research conducted by Anjali DasSarma, a doctoral candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.

This piece was edited by James Salanga. Copy edits by Jen Ramos Eisen.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director