What I learned by trying to quantify anti-trans bias and objectivity

If a source argued that someone doesn’t exist and they do, we would take a picture of that person and run it at the top of the article. So why aren’t journalists quoting trans people about executive orders that challenge our existence?

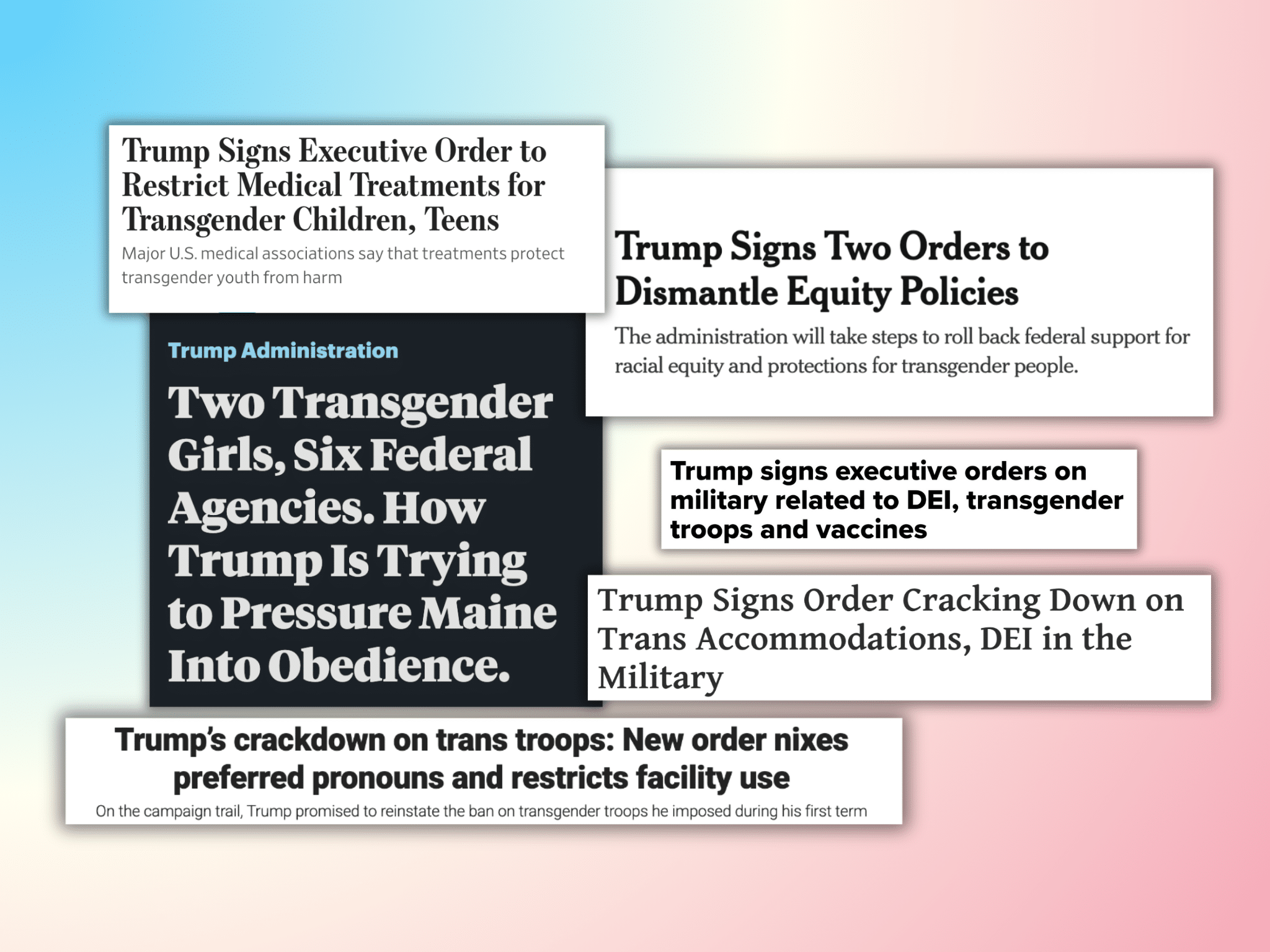

In January, President Donald Trump signed an executive order titled, in part, “Defending Women From Gender Ideology Extremism.” The order explicitly redefines sex and gender to state that two sexes are “not changeable” and are “grounded in fundamental and incontrovertible reality.”

In short: The U.S. government was arguing trans people do not exist. It said it would take steps to make that argument true at the administrative level — in “all institutions of society.”

All told, by the end of his first 100 days, Trump had signed 143 executive orders; by my count, at least 15 — more than 10% — relate to sex and gender. This has led to takedowns of LGBTQ+ data collections to ICE no longer reporting information on trans detainees to revised airline and customs identity verification processes and more. By any definition, that’s a huge news story, and a matter of public importance.

The Trans Journalists Association wanted to understand how journalists would cover this. A coverage audit developed with researchers at Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) found that news stories largely framed the executive order as what the story evaluators described as a “political football” — trans people rarely got to speak for themselves as politicians debated their place in society. Few stories went beyond that.

Our process raised questions about the core idea behind “balance,” how we would measure it — and what journalists are missing by not looking beyond it. We also wanted to see if stories accounted for our guidance and framing advice.

BMSG’s researchers developed a stratified sample of national outlets. The sample represented what the public may generally read, while remaining a manageable volume for an analysis that wouldn’t take five years.

Our questions became: How can we evaluate the coverage? How do we meaningfully quantify journalistic values like balance and fairness, objectivity and truth? How do you measure value to the public?

After a lot of article analysis to answer these questions, ranging from evaluating accuracy to cross-checking articles’ inclusion of policy consequences, we reviewed the results. Then we settled on a very basic, very traditional focus: sourcing.

Clearly identified Republicans spoke in 50% of stories; clearly identified Democrats spoke in only 32%. That disparity across the aisle shows an obvious deviation from the most traditional and simplistic notions of objectivity: You quote both sides.

Yet quoting Democrats wouldn’t fix many of these stories, because many of the politicians who spoke about the trans executive orders, whether Republican or Democrat, had very little to do with them. They didn’t write them, they weren’t implementing them, and they weren’t doing anything concrete to counter them. Generally, they just contributed rhetoric. Not news.

So these metrics alone didn’t articulate the larger problem: Few stories quoted trans people alongside those politicians. Barely any quoted trans children or young adults under 20, even though their futures are a huge piece of the national conversation. Even prior to these executive orders, more than half of states in the U.S. had already passed laws restricting trans youths’ rights. This legislation not only shirks protections from bullying and conversion therapy, but targets their ability to participate in social spaces, to choose their own healthcare even with parental support, and to speak freely about their own identities and experiences in classrooms. (As it becomes more dangerous to go on-record — following adult-run harassment campaigns against teenagers quoted in news stories — this absence of perspective may very well get worse.)

The common argument in favor of quoting a trans person here: journalists’ stories are stronger when they’re sourced diversely. That’s true and important. But there’s an even bigger obligation here. These executive orders have sought to entirely redefine who is American — who lives here, who doesn’t, who deserves rights, who doesn’t, who is a part of society, and who isn’t. Trans people — who the U.S. government has recently called “gender identity extremists” — have been accused of “inflicting harm on our nation’s children.” We may, perhaps, be among those animated by “anti-Americanism, anti-capitalism, and anti-Christianity” due to “extremism on migration, race, and gender,” as described in the related presidential memorandum on rooting out “organized political violence.”

Fixing the journalism covering these claims doesn’t require a radical re-understanding of balance and objectivity.

No editor I worked with as a cub reporter would have published a story where a politician accused someone of being an “extremist” or “inflicting harm on our nation’s children” without asking that person for a response. If a source argued that someone doesn’t exist, and they do, we would take a picture of that person and run it at the top of the article.

That’s just journalism 101.

But the unfortunate flip side is, quoting trans people isn’t a quick fix, either. Just like quoting an extra politician doesn’t automatically lead to balance, quoting the communities at the center of these debates only goes so far. Plenty of poorly framed journalism still has robust sourcing.

Quoting more trans people is a start. But we need to think clearly about what stories we’re telling. What’s the point of so much news that doesn’t look beyond the theoretical realm of the political debate? Who is news for, and what is it doing? How is it equipping the many Americans facing increasingly restricted civil rights and a worsening quality of life to understand and navigate the turbulent world around us? How does it build community and foster civic dialogue to weather attacks on personhood?

In a time where the government is trying to radically redefine who is a member of our democracy, what role do journalists play in humanizing the dehumanized, pushing back on demonization, and identifying hatred and falsehoods for what they are?

There are many ways all of us can answer those questions. My answers are inspired by journalists both globally and locally, whether they’ve held powerful governments to account or shown entire towns the true face of hatred in their communities. In the service of this, I edit studies and tools like the forthcoming Trans News Initiative to help journalists see where we aren’t doing this, and the TJA Resource Hub, to assist those who want to do more of this work.

Ultimately, I’m trying to enable journalism that shows the truth of this moment, and the people living through it.

I hope you will, too.

Kae Petrin is a data journalist and media educator who co-founded the Trans Journalists Association in 2020.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director