‘No long-term vision’: after layoffs, staffers say L.A. Times lacks plan for future

After one of the largest layoffs in Times history, journalists fear impact on newsroom diversity and coverage amid their union’s fight for a fairer outcome.

When the news first broke Tuesday morning that the Los Angeles Times would be laying off at least 115 people — upwards of 20% of the newsroom — impacted staffers learned of their fates in a myriad of different ways.

Some received emails from HR informing them that their positions had been eliminated, inviting them to a webinar on the topic later in the day. Others received texts or calls from colleagues and were told their entire teams had been decimated.

Other staffers tried to open up Slack only to discover that their login credentials were no longer functional. Some employees who were initially told they’d been spared were told day later that they, in fact, would be laid off too.

“It was pandemonium,” one impacted employee, who requested anonymity to discuss private employment matters, told The Objective. “It was just technical chaos on top of actual employment chaos.”

That the layoffs were happening didn’t come as much of a surprise. Rumors about their size and scale began circling earlier this month, following executive editor Kevin Merida’s surprise exit from the masthead, and a report in the Times last week estimated the number of impacted staff to be “at least 100 journalists.”

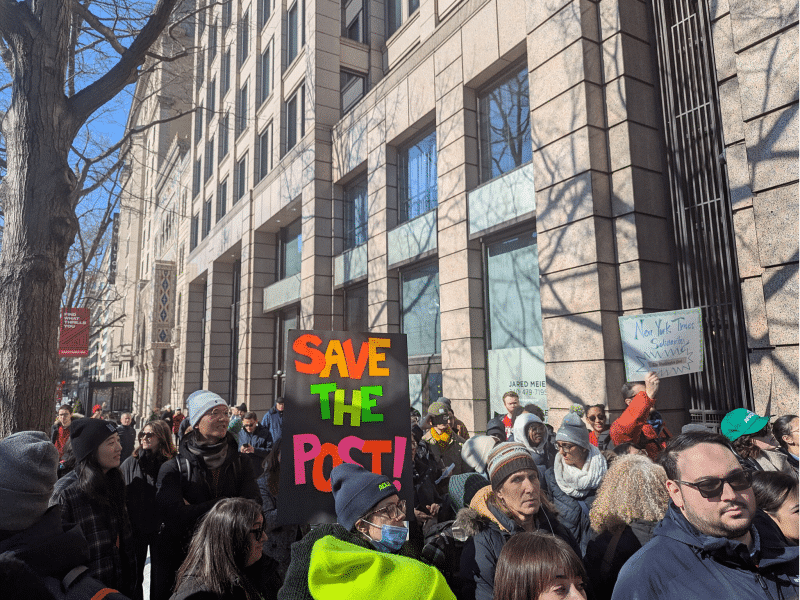

On Friday, around 350 members of the paper’s union held a one-day strike to protest the impending cuts, the first such action in the Times’ 142-year history.

But what was surprising, staffers said, was the speed at which they occurred: managers at the Times were not known for timely communication, and newsroom gossip had estimated the layoff announcement for sometime on Wednesday at the earliest.

“This is the one time they not only met a deadline, but came in early,” the newly laid-off employee mused.

Times leaders — chiefly Patrick Soon-Shiong, the biotech billionaire who purchased the paper in 2018 — have since argued that the drastic move was necessary to preserve the paper’s financial wellbeing.

“Today’s decision is painful for all, but it is imperative that we act urgently and take steps to build a sustainable and thriving paper for the next generation,” Soon-Shiong said in an interview published Tuesday in his own paper.

Yet interviews with current and former Times employees, as well as individuals outside the paper knowledgeable about its operations, say the economic crisis is largely one of Soon-Shiong’s own making. The trouble, they argue, is that the owner did not — and indeed, has yet to even now — articulate a clear vision for how the paper will become successful. And the cuts, if they proceed as expected, will undercut the papers’ previous public pronouncements attesting to the importance of improving diversity and representation in the newsroom.

“This storied brand has no strategy for how to operate a business in 2024,” said Gabriel Kahn, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism who studies contemporary newsroom business models. “The layoffs are basically a result of failure to define, articulate, and execute a real strategy.”

Diverse workers, stories bear brunt of mismanagement

Lending credence to Kahn’s argument is the fact that the paper underwent a similar round of layoffs barely seven months ago, where the 10% reduction in newsroom staff was similarly described as necessary to preserve long-term stability.

“We all knew that we were not doing well, that was explained,” said a former employee who was laid off last year. “But when editors and writers would ask, ‘Well, what is it that we can do differently?,’ the messaging was just, ‘Good storytelling.’”

“There was no long-term vision,” the person put bluntly.

Today, many in the newsroom are furious that they are the ones bearing the brunt of the cuts, when those in charge of the business decisions are most at fault.

Laid-off Times staffers and those still at the paper now hold two simultaneous concerns: how the cuts will impact themselves, and the communities they cover.

“[T]hose entrusted to steward [Soon-Shiong’s] family’s largesse have failed him — not the rank-and-file staff members with no say in editorial priorities,” read a statement from the L.A. Times Guild shared with The Objective on Tuesday evening.

“We still believe in the Los Angeles Times and the important role it plays in a vibrant democracy. But a newspaper can’t play that role when its staff has been cut to the bone.”

Should the layoffs proceed as expected, they’d amount to a 38% reduction in Latino Caucus membership, a 36% cut to Black Caucus membership, and a 34% reduction in the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) and Middle East, North Africa and South Asia (MENASA) Caucuses’ combined membership, according to a joint statement from caucus leaders.

Jeong Park — whose reporting was focused on AAPI communities — was also laid off, and the team behind the popular De Los vertical, which started last summer and focused on covering L.A.’s large Hispanic population, was mostly gutted.

“If these cuts are implemented, the newsroom of the Los Angeles Times will not look like the counties that it covers,” Gabriel San Román, a metro reporter who received a layoff notice, told The Objective.

The day before he learned his job had been eliminated, San Román was reporting at the picket line of the California Faculty Association strike, where he said someone approached him to compliment the Times for being “diverse and reflective of Southern California.”

“Can we say that, you know, come spring, when the layoffs become permanent?” he said with a sigh. “I don’t think so.”

And the layoffs don’t just reduce the paper’s capacity to deftly cover Southern California’s diverse communities, but could hamper its ability to attract new audiences.

Among the teams most impacted by the layoffs is the newly-formed 404, designed to encourage young readers to engage with Times content, along with the paper’s Washington bureau, where several reporters and two managers were served layoff notices. Those whose positions were not cut are expected to be transferred to other teams, one person said, all but eliminating the paper’s D.C.-based coverage.

All Black staffers at the Washington bureau were laid off.

“The fact that all these cuts came the day of the New Hampshire primary is just a testament to how little Patrick [Soon-Shiong] actually cares about democratic institutions,” said a staffer granted anonymity.

Times’ leadership plagued by decade of turmoil

The layoffs come as the Times has endured a rocky past decade plagued by turmoil, including personnel scandals, newsroom ethics squabbles, and a financial crisis brought on by declining print and advertising revenue.

In 2018, billionaire scientist and surgeon Patrick Soon-Shiong purchased the paper and the San Diego Union Tribune for $500 million from then-owner Tribune Publishing (later rebranded as Tronc), staving off a major layoff effort reportedly planned by the former publisher. With Soon-Shiong’s blessing, renowned journalist and editor Norman Pearlstine came out of retirement to lead the newsroom, quickly instituting a hiring spree with the hopes of returning the paper to its former glory.

Yet Pearlstine’s tenure coincided with a series of personnel crises that spilled into public view: a reckoning within the newsroom about race and representation in the wake of George Floyd’s murder; the investigation and ultimate resignation of sports columnist Arash Markazi for alleged plagiarism and ethical lapses; bullying and harassment allegations against food editor Peter Meehan, who later resigned, and masthead editor Colin Crawford, who retired abruptly.

All told, at least six prominent editors were “pushed out, demoted or had responsibilities reduced because of ethical lapses, bullying behavior or other failures of management” in the year after Pearlstine joined the paper, according to a lengthy investigation the Times published in 2020.

But major shake-ups to the paper’s masthead predated Pearlstine’s hiring.

In 2018, then-publisher Ross Levinsohn took unpaid leave from his post after an NPR investigation revealed he was the subject of multiple allegations of workplace harassment. Around the same time, editor-in-chief Lewis D’Vorkin was ousted following the publication of a scathing critique in the Columbia Journalism Review.

The year before, publisher-editor Davan Maharaj and four top editors were ousted from leadership after clashes with the paper’s then-owner, Tronc; Maharaj, in turn, leveraged a recording he’d made of Tronc Chairman Michael Ferro using an antisemitic slur to earn a secret $2.5 million payout. Ferro himself would later resign amid harassment allegations.

In 2020, Pearlstine announced his return to retirement, and six months later Kevin Merida was named as his successor. A former top editor at the Washington Post and ESPN, Merida was initially seen as something of a stabilizing force within the newsroom, someone who — like Pearlstine — could help the paper regain its reputation.

Yet amid an overall industry decline catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic outlook at the Times never improved, and the paper is now estimated to be losing more than $40 million a year.

Last June, Merida presided over a round of layoffs that eliminated 73 jobs, or more than 10% of the newsroom. A month later, Soon-Shiong sold the Union-Tribune to Alden Global Capital, a firm known to buy and downsize American papers.

Since then, relations between Merida and Times rank-and-file had been icy at best.

In November, the paper disciplined dozens of journalists who had signed an open letter calling on news organizations to more accurately and honestly cover Israeli military attacks on Gaza and condemning the nation’s killing of media workers there — a death toll now well over 100.

Then earlier this month, executive editor Merida announced his surprise departure from the paper over disputes about Soon-Shiong’s strategy, and just this week, managing editor Sara Yasin reportedly announced her intent to leave. Managing editor Shani Hilton is also reported to be exiting the company.

Now, newsroom staff say they just want to know who’s in charge.

“It is still unclear who is in charge of our newsroom more than a week after our executive editor resigned,” the Guild noted in its Tuesday statement.

The Times announced Thursday morning that Terry Tang, the editorial page editor, would take over leadership duties on an interim basis.

Guild remains strong despite union-busting tactics

In addition to the sadness and fear accompanying the loss of one’s job, some staffers at the paper have described a newfound frustration towards managers for what they see as anti-union tactics to disrupt staff unity.

Late last week, as rumors of the impending cuts began to spread, unionized staff became incensed upon learning that newsroom leaders sought to circumvent seniority protections baked into their contract in exchange for reducing the total number of jobs on the chopping block — something interpreted by many as a means of pitting younger staff of color against their more senior white colleagues.

“[Soon-Shiong] presented us with a false choice between saving diversity or saving seniority,” the anonymous staffer said. “We didn’t play ball.”

In response to the journalists who participated in the subsequent walkout on Friday, managers docked pay of those who participated and temporarily cut off access to striking journalists’ Slack and email accounts, because “it was expected that those who were participating in the strike would not be working,” vice president for communication Hillary Manning told The Objective in an email.

Most recently, some staff who were served layoff notices were turned away by security ahead of a previously-scheduled meeting between Guild leaders and newsroom leaders Wednesday morning, even though impacted employees will remain on the payroll through March.

Manning did not respond to an inquiry about staffers being prevented from entering their office building.

While the situation is dire for those set to be laid off, those whose jobs were spared aren’t faring much better; they’ll now have even more work to do with fewer resources to do it.

“These cuts are so severe that, whether you’re laid off or not, the culture, the texture of what makes the L.A. Times the L.A. Times is going to erode,” argued the newly laid-off employee.

Such fears were echoed by industry-watchers like Kahn, the USC researcher studying media business.

“These cuts go right to the bone,” he said. “You’re just not going to be performing at the same level as you were, there’s no way around that.”

But despite the poor morale, unionized staff say they intend to fight for a fair and just outcome until the bitter end.

“The Guild will not be deterred or intimidated,” union leaders wrote in their statement. “We will continue to fight for our members and for the future of the Los Angeles Times.”

According to those involved, that battle encompasses careful scrutiny of the processes by which managers are pursuing layoffs to ensure they comply with contract terms, as well as a push to pursue a newsroom reduction via buyouts instead of layoffs.

“Even though it feels like a very grave situation, the finality of it is, I haven’t signed any paperwork, so it’s not a done deal yet,” San Román said.

“This is only the beginning, and a true inflection point for the future of journalism,” he added. “I didn’t go down without a fight, so I don’t expect my union to do anything different.”

Editor’s note: Los Angeles-based journalist Emily Elena Dugdale started a mutual aid network to support laid-off journalists impacted by the Times layoffs. More information can be found here.

Jacob Gardenswartz is a reporter based in Washington, D.C covering how politics and policy impact people.

This piece was edited by Omar Rashad. Copy edits by James Salanga.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director