Five years later, the AP still inconsistently describes George Floyd’s murder

The major newswire service continues to use passive voice when describing a crucial flashpoint of police violence.

In 2020, it took several days for newsrooms to directly say police killed George Floyd — despite footage that showed a police officer kneeling on Floyd’s throat for nearly 10 minutes.

Though the murder was caught on video, resulting coverage from the Associated Press continued to refer to it as a “death” in headlines, not a killing, including in their story on the officers’ firing.

Based on the headline, a reader might be unclear why those officers were fired: “Four Minneapolis officers fired after death of black man.” The lead image for the story is meant to connect the dots — it’s a screenshot of footage of the murder. Five years later, the AP’s retrospective coverage now identifies George Floyd’s murder as what it is, and has confirmed via an Ask an Editor response that it is appropriate to identify the murder as such. But the newsroom doesn’t consistently adhere to its own style principles or cover journalism’s role in incomplete reporting on police violence and the broader history of its severity in the U.S.

Newsrooms that continue to use passive voice even when it’s clear who perpetrated violence may be doing so “out of mimicry and habit rather than strategy,” Karen Yin, the author of the Conscious Style Guide, told The Objective.

“When police narratives intentionally obscure police violence, and newsrooms repeatedly adopt the same wording, this normalizes passive voice to the point where active voice and naming the doer can start to feel unnecessarily harsh,” she said.

Related: Q&A: Karen Yin

Language that fails to be specific about who is perpetuating violence has real impacts: a working paper published in the National Bureau of Economic Research in 2022 and revised last year found that after reading news stories with indirect or passive language about police killings, people were more likely to support police funding. And those stories were most common when victims were unarmed, not fleeing, or had their murder captured on video footage.

Even years later, stories syndicating AP’s “Today in History” coverage for May 25, at the expense of saying who killed Floyd, the national newswire still adopts passive voice: “George Floyd, a Black man, was killed when a white Minneapolis police officer pressed his knee on Floyd’s neck for 9 1/2 minutes while Floyd was handcuffed and pleading that he couldn’t breathe.”

Associated Press stylebook guidelines require an official murder charge to identify a homicide as such to avoid libel charges. It showed in early reporting: MINNEAPOLIS COP WHO KNELT ON GEORGE FLOYD’S NECK ARRESTED, an Associated Press headline initially read. (A near-identical variation of that headline is still present as a SEO headline for one of the major outlets across the country that syndicated the story, like the L.A. Times.)

But even after Derek Chauvin, the officer who killed Floyd, was convicted of murder, language remained unclear and inconsistent with AP’s policies. The story used the phrase “one of the longest prison terms ever imposed on a U.S. police officer in the killing of a Black person,” which, according to the AP’s own policy, could have instead directly said “a U.S. police officer who killed a Black person.” In 2023, the AP moved to call it a murder in the body of that year’s retrospective story, but not in its headline.

That inconsistency is on display even now, with the tag used to identify related content on the AP website still titled the “death of George Floyd” — not the murder.

“‘Death’ has been accurate and appropriate since before the charges and conviction,” AP media relations manager Nicole Weir said via email, noting that both terms are accurate.

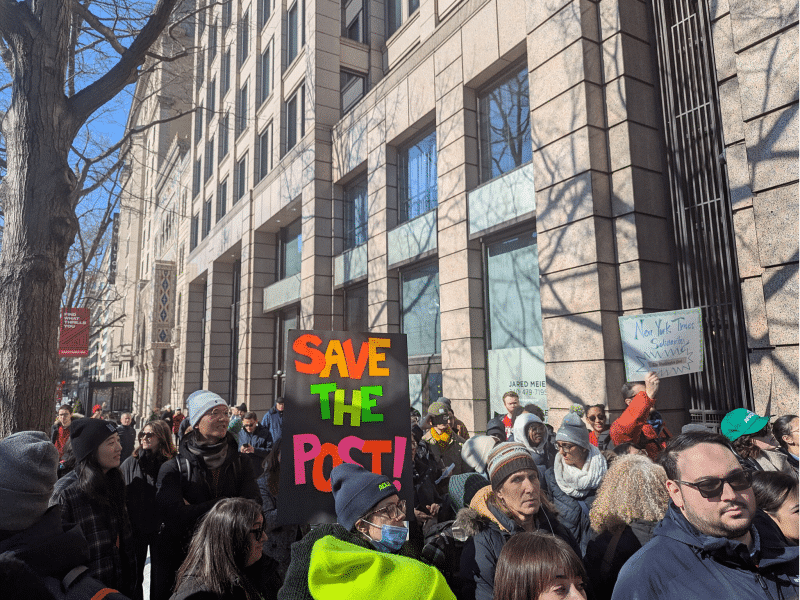

The anniversary of the murder arrives in a political climate under which the Trump administration aims to roll back civil rights protections aimed at desegregation. The Minneapolis police budget has gone up by tens of millions of dollars since 2020, despite an initial decrease in 2021. Diversity, equity, and inclusion departments and initiatives that sprang up to address racist news coverage have shuttered or pivoted.

Changes that erupted around the implicit and explicit racism Black journalists endured in both workplaces and coverage, like greater funding for Black-owned media outlets, have stagnated or started to revert. Still, some outlets are aiming to cover police violence both with clearer, more specific language and beyond the interpersonal.

The Don’t be a Copagandist style guide developed by Interrupting Criminalization advocates against using passive language, like saying someone “died at the hands of police,” to describe police violence.

“Telling the truth requires bravery,” Yin said. “If you shy away from the facts, make sure there’s a good reason.”

Update, Wed. May 28, 2025: This story was updated with additional comments from the AP.

Lewis Raven Wallace, who works as Interrupting Criminalization’s Abolition Journalism Fellow, is part of The Objective’s advisory board. He did not review this story before publication.

This story was edited by Gabe Schneider.

James Salanga is the co-director of The Objective and the podcast producer for The Sick Times.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director