‘No act of journalism … is too small’: Creating necessary archives

The threat to our stories of liberation and justice is real and ongoing. But through archiving, even if we lose our fights, the next generations have a shot at learning what we attempted and how.

This piece is part of the column series ‘The Case for Movement Journalism‘. Read other column installments here.

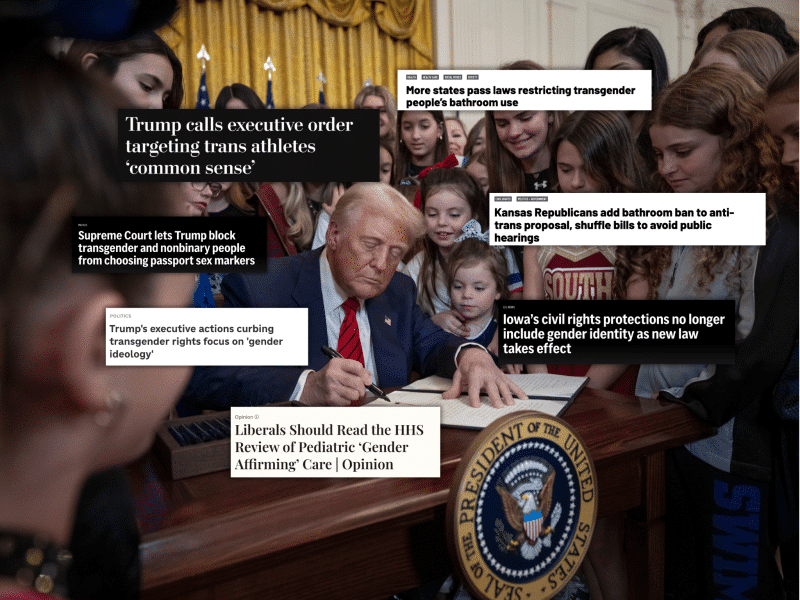

When authoritarian governments want to make dissidents and queers disappear, one of their first moves is to extract us from the archives. In just the first two months of the second Trump administration, hundreds of pages disappeared from government websites. Pages honoring Black, Navajo, and Japanese soldiers and pilots, pages recognizing LGBTQ history and the Stonewall uprisings, pages with any mention of transgender people, immigrants, women, or diversity all went away as archivists and activists raced to preserve them. (Some, such as Department of Defense websites about Navajo Code Talkers and the Tuskegee Airmen, were later returned to view after a public outcry.) State and local governments are actively pursuing authoritarian book bans inside of public schools and libraries, and in many state prisons, many materials that revealed resistance or discuss race or gender have already been systematically censored for years.

I think of archives as possibly the simplest and most attainable purpose for movement journalism — the “slam dunk” purpose. What we create doesn’t have to reach a large audience. It doesn’t have to contain every voice or address every angle. It just has to document the truth right now, to get a story of struggle or survival into an archive that lasts long enough for another generation to see.

The threat to our stories of liberation and justice is real and ongoing. But through archiving, even if we lose our fights, the next generations have a shot at learning what we attempted and how — and countless people have been inspired by the unlikely documentation of courageous acts in history, from Spartacus’ slave rebellion to the tales of Haitian Revolution, the underground railroad, and global LGBTQ movements.

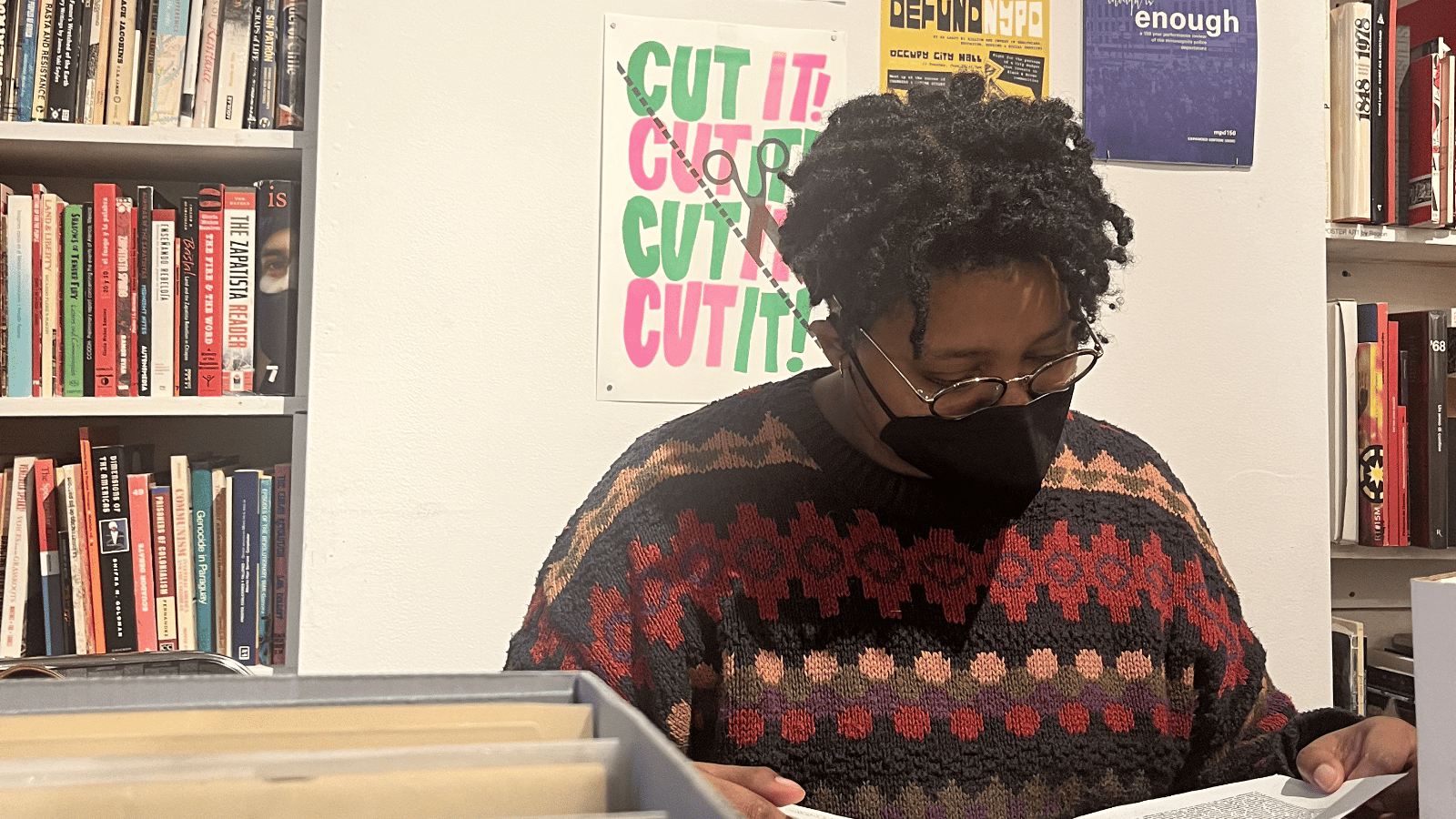

“When I saw archives of Black women organizing, or of queer folks surviving and thriving in the 20th century, it was foundational to my identity formation,” said Ashby Combahee, a librarian and archivist at Highlander Center.

As trans, Black, queer, and immigrant stories are being erased from official archives, movement journalists continue to document our communities’ stories, cultural traditions, music, and visual creations. Even acts of movement media-making that may initially only reach tiny audiences might have the monumental impact of preserving a fuller narrative of the present for people in the future.

In 2020, Combahee cofounded Georgia Dusk, a southern liberation oral history, with their friend Dartricia Rollins. While living in Atlanta and working in reproductive justice movements alongside other young Black feminists, Combahee said they noticed “this brilliance … kind of circulating around our organizations.”

“I wanted to better understand the connections between everyone, and I wanted to better understand this whole ecosystem of Black feminist organizing,” they said.

Combahee says archives of movement building and liberation are not limited to acts of written journalism: they can be physical collections of items, digital collections of oral histories, texts, and images, or even embodied artifacts like songs and food traditions, passed down from generation to generation. An archive, according to an interview they did with the Lesbian Herstory Archives, is simply “a collection that lasts beyond one generation.”

Subscribe and get each issue in your inbox

Georgia Dusk, as its cofounders describe it, is “an intergenerational counter-narrative to the mainstream depiction of Georgia politics and the southern liberation movement. As experts of our own stories, we document grassroots movements led by Black queer and feminist people and reclaim the historical representation of liberation movements throughout Georgia.”

The archive’s workers have since recorded four collections of southern oral histories focused on Black feminist activists: two about the reproductive justice movement, one focused on Black feminist futures, and one about the Mother Power movement, a woman-led fight to reimagine welfare in the 1960s and 1970s. Combahee hopes these stories — archived on George Dusk’s website, on hard drives in Combahee’s possession, and in the archives of the organizations they partnered with — will inform and inspire future generations.

“The whole purpose for me of doing movement memory work is that we feel rooted in the stories of resistance right here in the land that we call home, so that we can stay here, and stay fighting here,” Combahee said.

Journalism is often talked about as the first draft of history, but historians know archives are built on more than just the work of professional journalists. Our understandings of the past accumulate through first-hand accounts, poetry, song, recipes, oral traditions, recordings of speech and folk music, and preserved documents, ranging from ‘zines and fliers, to written plans for protests and workshops, to snail mail letters sent by USPS — another institution under attack by authoritarians.

I believe all movement journalists, even at the smallest scale, are potentially archivists, and every archivist is potentially committing acts of journalism, telling what is true for current or future audiences.

To create this movement archive, all you need to do is make your thing, and make sure it exists somewhere where it will be preserved and where it can be found. When I reported stories for WYSO Public Radio about the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014, I used to tell myself that even if the movement didn’t achieve justice that year, or that decade, we were creating an archive of what and how people had tried. The people who died at the hands of the police, who were named in our stories, would not be forgotten.

Ashby Combahee and others have taken to calling archival creators, those who hold the stories of marginalized communities and political struggles that simply don’t get told in mainstream media, “movement memory workers.” They are also defenders of these archives — protecting and preserving the first drafts of history so that people in the future can continue to learn from both our successes and our mistakes. Our stories’ survival depends on public libraries, public universities, and non-corporate grassroots spaces for learning and connection where both physical and digital archives can live continually.

No act of journalism or archiving is too small. If we do nothing else as storytellers, at least we can capture and archive images and stories of resistance. Maybe there will be people in the future who look to us for wisdom and strength to survive their own moment and mount their own acts of defiance. Maybe these archives will become a source of celebration, a record of victories that once seemed impossible as well as a record of strategies attempted and failed. Whatever the outcome, each bit of documentation we do now — whether through ‘zines, oral histories, audio interviews, video clips, podcasts, photographs, songs, or even memories passed down by spoken word — keeps our struggles from being erased by a repressive regime.

Lewis Raven Wallace is the Abolition Journalism Fellow at Interrupting Criminalization and the author of The View From Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity and the forthcoming title Radical Unlearning. They live in North Carolina.

This piece was edited by James Salanga.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director