Stories are an ‘arrow in a quiver’

How movement journalists share strategy and inspire action.

This piece is part of the column series ‘The Case for Movement Journalism‘. Read other column installments here.

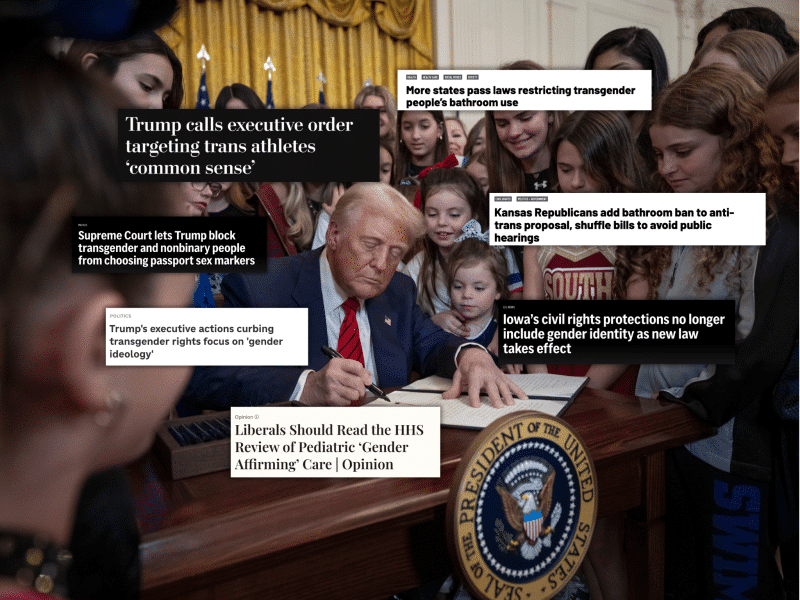

“Erin In the Morning,” the popular Substack and social media accounts run by trans movement journalist Erin Reed, started out of necessity: Reed was beginning her medical transition, and found it difficult to navigate where to get hormone therapy.

“I set out just to map all of the clinics that are out there, and I created a little Google map,” she said, and after releasing the resource online, other people started adding their clinic information, too. Reed says the map has now been accessed at least 12 million times. “I can’t enter into a space with trans people without somebody telling me that they were able to transition because of that map.”

Reed didn’t set out to become a journalist, but this project put her on the path. As the Christian right’s efforts to organize anti-trans backlash began succeeding at the state level, Reed says she found herself at the nexus of people who were fighting against attacks on health care for trans youth, and those who had key information about local trans health resources — the clinics and organizations that went into her first mapping project.

“I could ask somebody in Arkansas, ‘Hey, this bill, what does it do to your clinic?’ And they would tell me, and then I would report on it on Twitter,” she said. “People started following me. People started relying on the information that I was putting out.”

Before long, Reed migrated from then-Twitter to TikTok, and began putting out information via short videos. She started a Substack and quit her day job — and was soon able to sustain her life from paid subscriptions.

Movement journalism at its best can share strategy and inspiration among people taking action in local communities. The objectivity myth in mainstream journalism requires journalists to pretend their stories exist for no particular purpose other than truth; movement journalists can be more realistic and exacting.

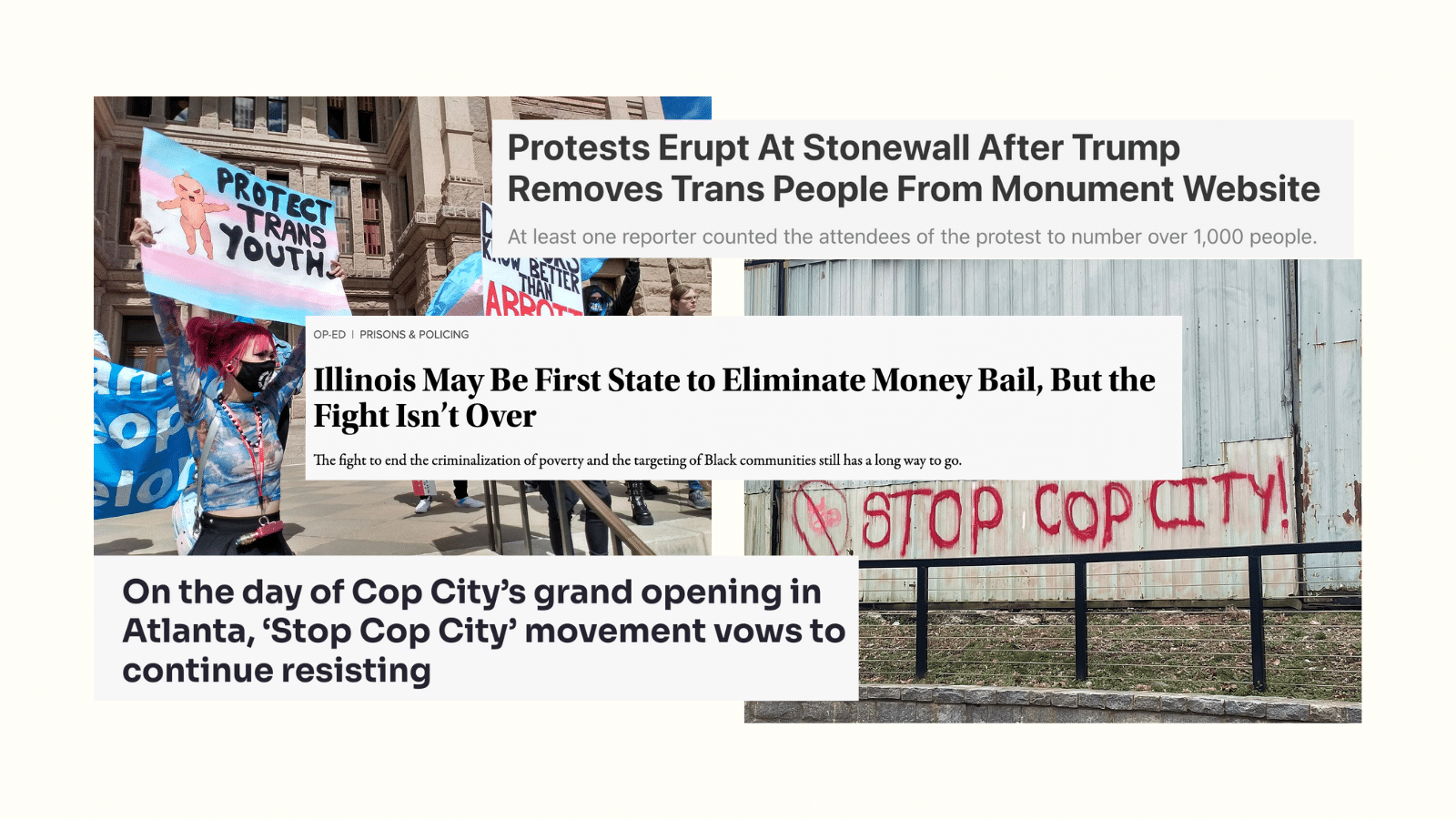

Maya Schenwar, director of Truthout’s Center for Grassroots Journalism, says it’s why Truthout asks organizers themselves to document their organizing strategies and experiences, instead of sending in an outside reporter who might miss the things that matter most to people actually doing the work. Other examples of movement journalism sharing strategy include Erin in the Morning; grassroots journalism outlets Mainline and the Atlanta Community Press Collective’s persistent coverage of the Stop Cop City movement in Atlanta, which helped groups around the country identify similar police training center proposals in their communities and build a movement to stop them; and Kelly Hayes’ popular Chicago-based reporting via podcast and newsletter, which helped drive mutual aid networks earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic and frequently highlights local grassroots action and gives specific suggestions for participation. Scalawag Magazine, Convergence, and Hammer & Hope all provide platforms for sharing strategies on the Left, each with a different focus.

One key difference between these outlets and more mainstream coverage is that movement journalists are strategic about what they put out and what effect it might have in the world. “Sometimes it’s good for people to see how the veggie sausage gets made,” Schenwar, at Truthout, said about inviting organizers to write about their experiences. “So much organizing just doesn’t get written down, and people have these victories, and people make these mistakes, and then the history is lost and then everyone’s reinventing the wheel.”

Reed said she imagines her stories as arrows in a quiver that someone can pull out and use when confronting disinformation or pushing for action.

This strategic news judgement sometimes means orienting coverage towards a very specific audience (in Reed’s case: organizers, for example, or parents of trans kids) rather than focusing on clickbait and aiming broader to garner a larger audience without including any potential actions for readers to change a situation. Reed’s popularity shows this coverage strategy is an antidote to hopelessness under an onslaught of hostile policies, but being useful doesn’t preclude being widely-read.

“There have been many cases where I have reported on things that are actionable, things that can be addressed, things that can be protested, things that change and watched people take actions and watched those changes,” said Reed. For example, Erin In the Morning’s coverage of healthcare clinics and hospitals dropping trans coverage and removing the word transgender from their websites — one form of advance compliance — led to protests in multiple additional locations.

Her subsequent coverage of those actions inspired others to protest, too: “I remember actually seeing a sign that said ‘Read Erin in the Morning’ at one of the protests,” she said. “That made me feel really good about what I’m doing.”

She says her audience — a mix of trans people, parents and families of trans people, politicos, and journalists — is highly engaged on the platform, and she also gets tips all the time via Signal groups and social spaces she’s in. The result has been a high-volume outlet that frequently breaks news about trans political issues, and an online community of people who share information directly with each other, creating a cycle of inspired action.

That’s why at Truthout, Schenwar commissioned coverage of the campaign to abolish money bail after it succeeded in Illinois so others could learn from that work — not just about how to abolish bail, but how to organize and win a campaign in general.

“Of course, there’s no roadmap to abolishing bond,” she said. “But there are a lot of tips and tricks. There’s a lot of trial and error that people could learn from.”

Beyond the specificities of strategy, Kelly Hayes of Movement Memos and Truthout says it’s important for journalism at large to focus on strategy and action, because it gets people out of repeated cycles of doomscrolling and reading and sharing based on outrage and disappointment.

“We need media that doesn’t just document what’s broken, but invites people on a journey that feels alive and worth taking,” Hayes said in a written interview. “Journalism shouldn’t just name harms and their architects; it should also illuminate possibilities for collective action and transformation.”

Journalism that focuses on action can do this lofty work of helping people feel alive, feel connected to struggle, reflect back a world where people don’t just passively allow repression and violence but instead respond with community action. The struggles we write about don’t have to be perfect — in fact, the kinds of articles that really help people are not PR releases for organizations but real breakdowns of tactics that have and haven’t worked, real descriptions of the ins and outs of a given strategy or approach. With stories like these, we don’t need doomscrolling.

Lewis Raven Wallace is the Abolition Journalism Fellow at Interrupting Criminalization and the author of The View From Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity and the forthcoming title Radical Unlearning. They live in North Carolina.

This piece was edited by James Salanga.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director