Q&A: Karen Attiah says her firing shows mainstream media still fails at talking about race

Karen Attiah, former long-time Washington Post opinion columnist and editor, sat down to talk about objectivity, “Democracy Dies in Darkness”, Black representation in news, and more.

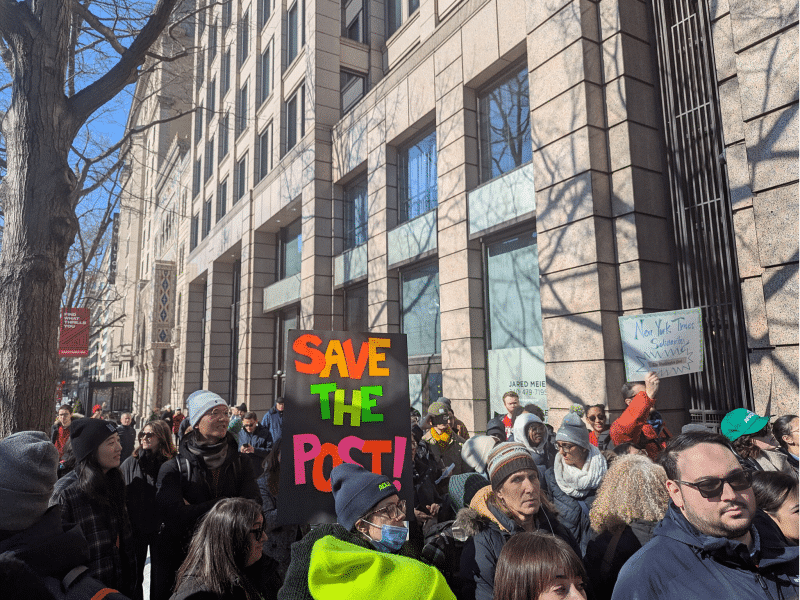

The Washington Post dismissed long-time opinion columnist Karen Attiah last month after she posted on Bluesky about the racist double standards around Christian nationalist Charlie Kirk’s killing and gun violence in the U.S. The Post informed her that she violated the paper’s social media policy.

Attiah, the last Black woman columnist on its Opinions team, maintains that her posts complied with the paper’s social media policy. She filed a grievance through the Post’s union, which has publicly backed her. The Washington Post Guild’s statement said Attiah was “wrongly fired” and that the newsroom’s decision “undermined its own mandate to be a champion of free speech.”

Her dismissal follows major editorial changes at the Post following longtime executive editor Sally Buzbee’s departure. Owner Jeff Bezos blocked Opinion staff’s editorial endorsing Kamala Harris for U.S. president and new leadership is steering the Opinions desk to focus on “personal liberties and free markets.” Dozens of the paper’s workers took buyouts after CEO Will Lewis offered them an out for those who decide they are unaligned with the new editorial direction.

Attiah sat down with The Objective to discuss objectivity, her take on “Democracy Dies in Darkness”, and Black representation at the Post and mainstream media at large.

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

It’s been over a month since you got the call from the Post. How are you feeling and what has the response you’ve gotten as you’ve shared the news of what happened?

Karen Attiah: I have to admit, it still feels strange, because the Post was part of my life for most of my working adult life.

I started in my late 20s, out of grad school, so it’s strange to be outside of that, you know? I still have my key cards to get into the building somewhere. This was a place I gave so much of my time and energy and soul, honestly. But that being said, I’ve gotten a lot of support.

A lot of people, especially in Washington, are in this season of having to reinvent themselves. A lot of people have been losing their jobs thanks to the political situation. What happened with me and the whole Charlie Kirk thing and just the nature of my job being high-profile was high-profile. But … a lot of people right now are like, “Wait, who am I outside of this title?” and having to figure that out and be independent right now.

I’ve got my cat, I’ve got good friends, I’ve got a good team supporting me, as well as just so many people from around the world who maybe have followed me for a long time and are just like, “We’re with you.” So that’s always nice to feel.

Is there anything you can say about the union support of you as you filed the grievance and generally in this time?

Attiah: The [Washington Post] union’s been great. Shout out to the union. They mobilized very quickly. The Post Guild issued a statement, as well as the larger guild, the Washington-Baltimore News Guild. I’m aware of my former colleagues doing a letter-writing campaign and getting a lot of messages for it. That’s definitely been heartening for sure.

Was there anyone who reached out about your dismissal that really surprised you in maybe a positive way? And is there anyone that maybe didn’t reach out that you kind of expected to or were hoping would?

Attiah: I’ll start with the first. I don’t know if it was an explicit reach-out, but definitely Barack Obama tweeting the story about my firing and then basically saying, “This is why we have a First Amendment, this is why media organizations need to not capitulate.”

Like that was pretty cool, especially given [that] anyone who’s read my work knows I’m not one to fangirl over any politicians in general — actually, my last political piece for the Post was criticizing Obama. For him to come back and basically be like, in my defense … was a much-needed boost in a really confusing and sort of crazy, hurtful time. I’ll have to say SZA tweeting about it was pretty cool, or posting on Instagram about it was pretty cool. I’m a long-time admirer of her.

Who was I surprised to not [have seen reach out]? It was pretty stunning that it was damn near impossible to get a sit down one-on-one with mainstream TV anchors, of whom I’ve been on their shows plenty of times, but at least in the first few weeks, they were pretty quiet. Jimmy Kimmel was talked about, but me at a place like the Washington Post — the last Black woman columnist in the Opinion section, and I’ve been on their shows a lot — it was crickets.

So that was pretty tough to see.

You’ve been at the Post for over a decade. But in the past year, there was a flurry of changes to editorial direction at the newsroom. For you, what was the importance of continuing to use your voice at the Post specifically, as opposed to maybe another mainstream outlet, say The Atlantic or the New York Times?

Attiah: Yeah, that’s a good question. A majority of my time at the Post has been as an editor. I think at a lot of other places, it’s very hard to have such a range of hats and experiences — I was able to help even craft the social media guidelines for the Opinion section when I first got on. Going into being an actual assigning editor, I was able to have the power to recruit people and really help shape coverage of the world through writers from around the world.

So I think for me, it was a unique time and opportunity. And then I transitioned a bit more into writing … but then I was also still contributing as an editor and editing pieces from presidents to normal folks in the city. So I got a lot of freedom and flexibility that is very difficult to get at a lot of places that might be more rigid.

And also, I think this is just such a vibrant and interesting city and area, the DMV area, that I was growing to love and wanted to help do more about the region, about the folks here. We have so much in our backyard, so many storied institutions … I love New York, I’ve lived in New York, but … Washington [D.C.] is interesting. It’s an international city. It’s also a city with its own local culture. It’s a city that is very diverse. So I just was like, “Yeah, it makes sense to be here.”

That also makes me think about something you wrote about in your Substack — with your departure, the Post is not really a paper that reflects D.C., especially on the opinion desk. Do you feel like there are local D.C. outlets that do reflect the majority-Black population of D.C.? And what are your thoughts about where the Post can go [from here], especially because I think that has been a common critique, the lack of Black representation at the Post in this city specifically?

Attiah: This is something, obviously, NABJ raised with the news leadership. I’m not aware if they raised this directly with Opinions.

I’ve long said that the lack of Black opinion journalists and editors in general throughout America is systemic and deliberate. Opinion journalists get a wider berth to literally help shape thought — to go beyond the who, what, when, where, why, but to also be able to advocate and have positions.

[In terms of local news], there’s Washington City Paper, that’s still here. The 51st has been a really interesting startup, an independent news startup, which I think may have some former Posties in it. A lot of people, to be honest, are getting a lot of their news about D.C. from social media and Instagram. I know so many people who are getting news and views from, like, Washingtonian Problems. I just did an interview with Kymone Freeman [of We Act Radio] on the radio network. There are independent, Black-run, Black-owned outlets here.

But yeah, the Post is this nationally, globally recognized brand — not just a recognized brand, but a place that has had incredible Black representation in the past, foreign correspondents … Not completely, but it used to do a much, much, much better job at hiring and retaining Black talent.

Now they don’t seem to care. I think that there’s now, I guess, an opportunity left with the vacuum at the Post. It’s pretty stunning that they’re so bold about this purge.

Related: Q&A: The 51st aims to replace DCist with something totally new

Over the decade-plus that you were at the Post, how would you characterize the Post’s attitude towards attracting and retaining Black writers and Black editors?

Attiah: You know, as part of some of the pressure for the Post to better itself — it’s always a bit of a fight, but at least in the past, there were managers who were responsive to that.

But now, all of that has been washed away. I believe I’ve written this before, so it’s not anything new. It’s not just having Black writers or Black editors, even though that’s enough, but [having them be] representative — I think at least in my capacity, I was also doing my best to bring on [not just] other writers of color, but just different perspectives, different topics. Not just politics, but things that people wanted to read. Maybe it’s an unfortunate burden or tax that when you get into these spaces, you always feel an obligation to try to pull others up along with you.

If anything, I feel a lot of, I guess, pride, but also sadness, for the writers that I was able to bring on who now don’t have a home. Some of them said that working with me was the first time that they had ever been published in a mainstream outlet.

I think one worries about the pipeline. It’s not just Black journalists, now young journalists, diverse journalists don’t see a place for themselves at these papers. And it’s not just the Post, but papers that are reacting to this political climate. They’ve decided to put themselves at a competitive disadvantage while the other sources of information hold this racist status quo.

It really casts into stark contrast the slogan of the Post, “Democracy dies in darkness.” How have your thoughts on that slogan evolved given the recent changes and your firing?

Attiah: I came to the Post during the time that it was pulling itself out of this dust spiral that it was in. Jeff Bezos buys the paper around the same time we’re seeing the ascendancy of Trump, and there was a real, I think, political and social cultural climate of change and of this awareness that our democratic norms were being challenged.

But also, other things were being challenged, right? In 2014 or so was also the rise of Black Lives Matter. I started at the desk a couple of months before Ferguson happened.

There was a kind of revolution in some ways, 2014 to 2015. I think that the slogan “Democracy dies in darkness” came up at a time when we were really putting ourselves on the map for being sort of unapologetic not only about democracy, but also about issues of race. This was around the time of Me Too, so we were publishing a lot about women finally speaking out about abuse, and it was a lot of challenge to the system.

For some people, “Democracy dies in darkness” seemed a bit like Gotham, Batman, but I always saw it as a real kind of cry to the opposite … We have a responsibility to keep it alive and to keep the light on.

So for the Opinion section, at least, to evolve into what it’s become … that’s literally turning the lights out. I’ll be very interested to see what they do with this slogan. I feel like at least in my work, I’ve always been the same — always still very much believe in using the pen to, at the very least, hold the mirror up to society. Otherwise, you’re doing something very different than journalism.

I’m curious what it means to you [as an opinion columnist and editor] to strive for “objectivity” and how your perspective on that has changed through working at the Post and trying to platform many different columnists, like Jamal Khashoggi.

Attiah: I’ve always said that I believe objectivity is not the goal. It’s a means, it’s a tool, it’s a certain approach. Ultimately, what we’re trying to do is to try to collect as many perspectives as possible — just like from a scientific point of view. You’re trying to collect as much usable data as possible and with the data that you collect, come to the distilled form, essence of something, or you come to a cleaner version of truth. What we’re trying to do is to get at the truth of the world, and truth is messier than facts.

Objectivity, in my opinion, tends to all too often be a shield for ignoring information and perspectives that are inconvenient.

I used to also write some of the [Post] editorials. I still remember what my former boss and mentor used to say: Our privilege is that we get to write the world as we think it should be, not just as it is.

Both things [opinion and news] are necessary. Those things, I think, are symbiotic. Most of us who are opinion columnists, we’re also reporters. And we are trained in the objective thing, but we get the privilege of going beyond that. Applying logic and reason and experience and historical context in order to interpret those very objective facts. Particularly if you’re coming from a background that is not white, not male, [that] has never been considered “the normal”, you’re considered the other, right? Writing from your perspective is inherently all too often considered not objective.

“Objective” is often a stand-in for status quo, for “what’s normal”, for “familiar” … and objectivity is not very evenly applied, which makes me question whether or not it’s actually useful, particularly if you come from a background where the narratives have been distorted. I strive more for justice and balance … You can’t have objectivity if you’ve been erasing certain perspectives for all of history. That’s not objectivity, that’s just writing to preserve your power.

You mentioned helping work on the social media policies for the opinion section at the Post when you started. How have those changed in their codification and in their application?

Attiah: To be clear, I wrote some of the guidelines on best-use practices. I wasn’t involved in all the policies that were gonna be enforced through HR, but everyone kind of forgets that the Post was a bit archaic, even 12, 15 years ago, so they had to catch up on the social media train just like everybody else.

Obviously, social media has posed a serious opportunity and a challenge to normal media organizations. I mean, this is where we are able to see feedback and see criticism and see what various discourses are happening. That’s been a huge part of my career, is being able to pull those perspectives and those voices out of Twitter and say, “Hey, this person has a great Twitter thread. Let’s put this in the Washington Post for more people to see stuff like that.”

As a columnist, especially given that so much of our political discourse is happening online and in social media spaces, part of my job was to maintain a presence in those spaces. It was to talk about these issues, talk about my work, promote my viewpoints, particularly as a columnist that focuses on race and gender and culture. That was a part of the expectation.

So, I mean, back to the firing, this termination is just like — you fired me for doing my job. But they knew what they were signing up for. Part of the reason I filed a grievance is to challenge this. ‘Cause it does send a chilling message, particularly to opinion journalists, particularly to journalists who write about race.

The idea that describing a documented pattern or describing general patterns of violence, particularly [in my case] white men who carry out violence or espouse hatred was descriptive, not disparaging — I don’t think all white men are violent. I don’t think a massive majority of them are. Specifically, the ones who do carry out mass shootings and who do have bigoted points of view, that’s what I was talking about.

If we can’t talk about this, then that is very much the antithesis of objectivity. It sends, definitely, a chilling effect. Not only to the newsroom, but particularly for Black journalists, particularly Black women journalists. We gotta challenge this.

You’ve been on a lot of interviews with other media organizations, but is there anything that you’d like to share, especially for other journalists, that you maybe didn’t get a chance to through those venues?

Attiah: I’ve been saying this, but now is the time for solidarity. There was a perception that, just in general, when something happens to one group, “Oh, it’s not gonna happen to me.” If the opinion section was getting these purges and these mandates and things like that, this idea that it’s not gonna come for other sections or other groups was always gonna be naïve, I think.

This is at a time when race, especially, is in our face, right? This administration especially, when the New York Times just had a piece on all the purgings of Black senior leadership in the administration — these people can’t even handle the fact that Bad Bunny is gonna perform at the Super Bowl.

We’re in a time when issues of race and racism are so negative and so blatant that to run and avoid this issue would also be journalistic malpractice. I’ve said for years that mainstream media is not prepared to face what’s coming because it can’t even face its own racism problem.

If you can’t even face that, how are you going to be able to effectively drive, if not challenge, what’s happening on a governmental level and on a cultural level? I know at the beginning, a lot of people thought that I was fired because I quoted Charlie Kirk.

And again, that’s not true. At least according to the termination letter, they believed that I disparaged white men in the aftermath of Charlie Kirk, and it feels like people, especially the mainstream media, don’t want to have that conversation. So it’s easier to just believe, oh, it was a messed-up quote, but they really don’t want to face what the Post was actually telling its last Black [full-time] columnist, which was, “You did not mourn enough for Charlie Kirk and that simply describing violent white men in the political kingdom … that, apparently, is fireable.”

My case is a test case for how well media can talk about race. And so far, at least mainstream media has failed that. And if they were failing that in my case, then they’re not equipped to talk about what’s happening on a broader level, which is precisely why more people are going to independent media and social media who are less afraid to talk about this.

I’m curious about the timeline of the photoshoot [accompanying the Substack post you wrote about your firing].

Attiah: I’m surprised more people haven’t asked me about the photo shoot. I did that before this happened. I think I just had inklings of what could come. And it’s just been interesting because, I don’t know, I saw it as a way to express what I was doing. Express what was happening to journalism, maybe, and express what was happening in terms of responding in an artistic way to censorship.

It was interesting to see people’s different reactions. Some people were like, “Oh my gosh, this is in front of the Post, democracy dies in darkness and lighting a torch and journalism should be the way,” or people were like, “Oh my God, she’s burning [the Post].”

The right-wing freaked out over the photos. I think Rudy Giuliani was tweeting about it, like “Employers, would you employ someone who would do this to yours?” So shout out to my photographer, Ethan Wong, who shot that and helped kind of create the vibe and the mood.

And just to wrap things up: For you, what does justice and balance in media look like?

Attiah: Oh my gosh, what does justice and balance look like?

Well, maybe it’s what’s happening — the rebalancing and people, sadly, abandoning mainstream media because it hasn’t really served them. It’s both balanced and not balanced, right? It’s systemic in the sense that so many journalists who’ve been pushed out of mainstream spaces are finding their voices on places like Substack, on places like YouTube, on independent platforms, and are reaching more people and forming more of a connection with their audiences than they did with the mainstream media.

So maybe the Internet in many ways is an attempt [to rebalance], at least on a sort of individual level. I’m thinking of Don Lemon, Joy Reid, Jim Acosta, Roland Martin, those folks who have carved a path for themselves outside of these structures and are doing pretty well, right?

At the same time, that still doesn’t match the resources that these major publications have, both on a legal front and just the resources to be able to do really good independent reporting and investigative reporting very specifically.

I think that people, readers, listeners, watchers, viewers are more savvy than media tends to give credit for. People tend to find what they need, what they want. Perhaps even for me on a personal level, maybe this is my great rebalancing in the sense that now I can really do and say what I couldn’t, you know, in the past.

That being said, we’re in a very fractured media environment. And particularly with misinformation, social media, [and generative] AI coming, I’m afraid for all of us that soon, people won’t be able to distinguish facts and lies. We’re entering a time where people can create AI events and people that never happened in reality.

So as much as I think this is liberating, I feel like there are still so many dangers in the pipeline … We’re going back to a time where billionaires and oligarchs are using too many of our mainstream papers to push certain agendas that those of us who are now forced to be independent can at least be pushed back inside.

My last 11 years were at the Post doing mainstream media. The next 10 years will certainly be interesting, different to say the least. The media landscape — I keep joking to folks and to my team, like, “Is Substack the new public broadcaster? Is YouTube the new public broadcaster?” Particularly with these attacks against NPR, against PBS, we’re in a government shutdown already.

So what does the public square now look like?

Again, that’s just a bigger question about, is it possible to have justice and balance when most of your companies are owned by a handful of people and the majority of the social media ecosystem is owned by like three or four men?

I don’t know, but I still do think there’s opportunities for people to have their voices heard without gatekeepers.

James Salanga is the co-director of The Objective.

This piece was edited and copy edited by Gabe Schneider.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director