Do newsrooms need a memeologist?

In the age of meme-slop and digital newsrooms shuttering, internet culture reporters say mainstream media is ill-equipped to cover not just trends, but a radicalization that doesn’t look how it used to.

How do you report on a meme? Pepe the Frog might be the obvious case in point, a wildly popular meme figure whose meanings are many and whose symbology was clumsily explained by news media when its usage as a hate symbol gained the most traction.

But deeper down the iceberg are seemingly trivial instances, like Mitt Romney’s comment about “binders full of women” during a 2012 presidential debate with Barack Obama. The news media’s coverage consisted almost exclusively of two archetypes: either a collection of “internet reactions” passed off as analysis or arguments that Romney’s campaign could be hurt by being the butt of jokes. At that point, pre-Donald Trump’s first run at the presidency, there was nary a mention in major newspapers about how memes were recasting political discussion itself, let alone context that could help readers understand not just the apparent meaning of a meme but what they could actually portend in a shifting media environment.

The most visible and recent example of reporters’ struggle to explain the interplay between memes and political violence has been, of course, the effort to contextualize the inscriptions on bullet casings allegedly intended for Charlie Kirk’s assassination hours, days, and weeks after it happened.

Newsrooms floundered in their attempts to explain: The Wall Street Journal jumped on an unverified law enforcement report and spread misinformation by alleging one message referenced “transgender ideology”, a term taken from anti-trans activism. Other reporters then speculated another inscription bore anti-fascist messages — before tracking down the video game it seemed to reference instead, Helldivers 2. Another message seemed to refer to an Italian anti-fascist song, or another gamer reference to Far Cry 6, or a reference to a groyper-adjacent Spotify playlist. (That prompted context-via-quoting explainers.) The other message seemed to reference old memes about furries, though there were fewer explainer articles about that.

Pundits and commentators had much to say about this seemingly new phenomenon of ideology-via-bullet, ranging from armchair psychology to attempts at political point-scoring. As a typical piece in Politico, by Dylon Jones, put it:

In pointing to the shooter’s few memes-turned-bullets, even those of us with a pathological fluency for extreme internet-speak might as well be pointing at clouds. And even if we do see anything in them, it may not map neatly onto a political ideology you’ll find in Congress. The politics of the internet operate across different axes than just left and right, Democrat and Republican. Your views on immigration or tax policy or abortion might mark you as blue or red in this country — but does your favorite meme?

Reporting on this kind of difficult story unearths kernels of long-standing issues — most importantly an over-reliance on what law enforcement says. But this era is also undeniably marked by increased levels of mis- and disinformation, urged on by the Trump administration and further propelled by outrage-inducing algorithms and free-use artificial intelligence. In the age of meme-slop, radicalization doesn’t mean what it used to.

Yet that doesn’t fully explain how ill-equipped the news media seems to be to explain or contextualize what is going on, or to understand it to begin with. Internet culture reporters, though, say the solution isn’t quite as simple as newsrooms hiring memeologists to lurk deep in the online trenches, immersed in digital ephemera, patterns, and communities, able to tap into a lingua franca that would help to bridge these gaps.

A digital media implosion

It may seem quaint to suggest in 2025 that the mainstream media has trouble reporting on the internet — what else is new — but it’s worth pointing out how different the media landscape was even a decade ago. As digital media was ascendant, and outlets like Buzzfeed News dominated online discourse, traditional newsrooms felt they had to compete.

Taylor Lorenz, online culture journalist and writer of User Mag, attributed the closure of places with robust online culture reporting to media consolidation, and told The Objective that traditional media is “focused on speaking to elites.”

Ryan Broderick, who writes the Garbage Day newsletter about online culture, added that “the mainstream media — but especially televised media — has always had an issue talking about the internet due to tone.”

Unlike traditional media, he argues, the internet is “an extremely populist space with almost no real gatekeepers.”

“Any random stupid idea can become very popular, and it’s extremely hard to get on TV in a suit and tie and give these ideas both the seriousness and lack of seriousness they deserve,” Broderick said.

But rather than standing behind their reporters and investing more thoughtfully into internet coverage, most traditional newsrooms instead allowed themselves “to be weaponized by the far-right,” which Lorenz argues has led to fewer jobs for women and people of colour — who also tend to be precisely the people who understand these online communities best.

To do robust coverage of the internet requires actual investment, she adds, “which can make them a target” — especially in a media climate that features a lack of funding for digital and print alike, the endless parade of internet culture sites closing down, and an increased pushback on hiring, or retaining, diverse journalists. As the mainstream media has routinely given in to “bad faith campaigns, almost every single online culture reporter has been driven out of their newsroom.”

“They’ve learned it’s more profitable to align with the right,” Lorenz said. “They want the internet to go away because they want control back over the media landscape.”

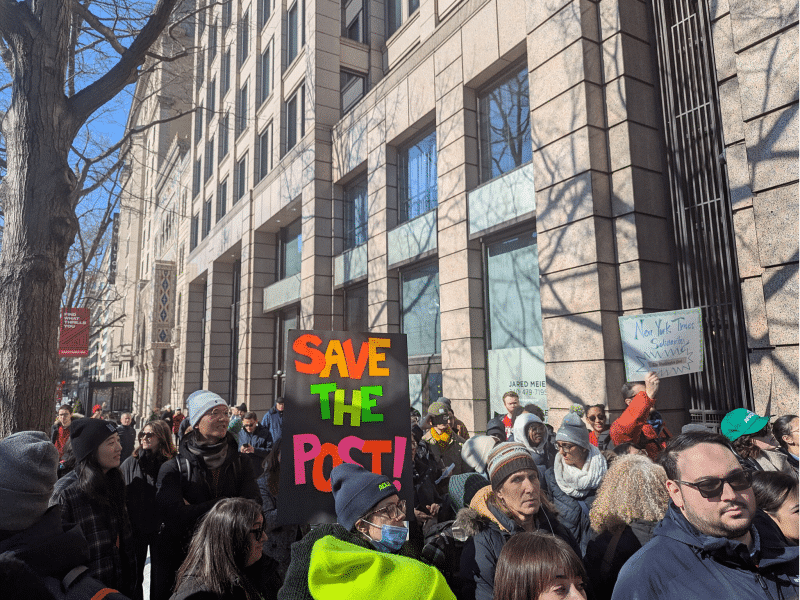

That desperate need for control seems particularly ill-advised for meeting the moment, with the best people to report on this political, cultural, and technological whirlwind being those least likely to remain stably employed at the biggest media organizations. (See, for instance, the recent dismantling of Teen Vogue, long a leader in progressive digital journalism.)

Related: Vogue guts Teen Vogue politics team

Part of the blame, Lorenz argued, can also be placed on what she called the “Gamergating of the entire internet.” The movement for “ethics in games journalism” was really just a bad-faith misogyny campaign, she said, and mainstream media seems to have learned (if anything) the wrong lessons from that firestorm.

Now, the ever-present tension when covering has only intensified as it has become clear that there is no distinction between what happens on the internet and what happens in “real life.” Think, for instance, of how social media policies over speech about subjects including the genocide in Gaza or Black Lives Matter operate as online and offline stories which influence each other.

“No one sounds good describing a meme out loud — it’s about as mortifying as describing a dream to someone,” Broderick said. “But this means that most major news sources oscillate between being overly-serious or completely flippant.”

The Substack solution?

While many journalists whose beat has been the internet may have been pushed out of their newsrooms in recent years, as the digital media sphere imploded, some — like Broderick and Lorenz — have found a home on Substack or other subscriber-based platforms, providing a more voice-first, independent approach to analyzing the internet and social media.

Many writers of colour who cover culture and tech, too, have made the switch to newsletter-writing, including Edward Ongweso Jr., formerly at Vice’s Motherboard, and Hunter Harris, formerly at New York Magazine. Recent research by Nelanthi Hewa and Nicole S. Cohen also shows, though, how many journalists of color have made this move to Substack only to find familiar obstacles: “Ultimately, we find that platform-based newsletters are not a neat break from existing power structures in contemporary media. Rather, Substack should be viewed as an extension — or a parallel track — of the industry it claims to be saving.”

So the fundamental problem remains twofold: mainstream media continues to erode its internet coverage, and these smaller newsletters simply don’t have the resources, financial, legal, or otherwise, to support proper investigative journalism.

As Lorenz notes, very few big publications are willing to take on these risks. Wired is an exception to the rule, as it published her bombshell piece about dark money funding Democratic influencer networks this summer.

But largely, she said, “there’s no one in these newsrooms that are able to take on these stories that may be more contentious which might require the news organization in question to defend their journalist.” Even if a Substack writer tried to do something similar, “you’d be sued out of existence.”

Another potentially promising example is a publication like 404 Media, a worker-owned and independent media company which is, more or less, entirely run by its four founders. They conduct investigations into online culture, cybersecurity, AI, privacy, and much more, and often break notable scoops.

Even so, they are likewise wholly subscriber-funded, and Lorenz says “they’re great, but that’s not a scalable system. They’re never going to be able to compete with” mainstream media.

While these smaller worker-led outfits and Substackers are doing their best to pick up the pieces of digital media journalism, they are up against an undeniably difficult landscape, during the Trump administration’s existing focus on mis/disinformation, its intensification via social algorithms and AI, and a decontextualized media ecosystem that would’ve seemed outlandish even to the reporters at Buzzfeed News a decade ago.

Still, 404 Media co-founder Sam Cole disagrees with Lorenz’s assessment of the subscriber-funded model — she said via email that it is “definitely scalable, and we’ve proven that by growing significantly as a company since launching two years ago.”

Cole cited the newsroom’s work in the last year: they launched another weekly newsletter, brought on several regular contributors and people to help us with socials and podcast production, sued ICE and the DHS, fought off a lawsuit from the state of Texas, and launched a new podcast interview series.

“We are actively keeping pace with the biggest mainstream outlets in the world, who cite our scoops constantly,” she said. “All of this requires financial resources and legal protections, all of which our subscribers make possible. We have always intended to scale at a sustainable pace, and I think we’re showing that it can work.”

But in the meantime, for traditional newsrooms, the lack of a so-called memeologist on staff — or at least a reporter steeped in Internet culture — means that the usual you can expect is an explainer of what “6 7” means, or, at best, an analysis of how far-right meme-speak plays a role in how Republicans talk to each other.

“It’s very easy for a newscaster to say that weird internet men are obsessed with a cartoon frog,” Broderick said. “It’s harder for them to come back a year later and say that the president is sharing the same cartoon frog and now it’s equivalent to a modern swastika.”

As “memes evolve over time,” he adds, extremists online “have learned that this shapeshifting effect is fantastic cover for them,” and the media struggles to sound credulous parsing it all. So while a memeologist could help newsrooms, a more pressing investment for them is to reckon with their more systemic failures to adapt accordingly, to covering online culture as a serious part of the news and information ecosystem.

Jake Pitre is a writer and scholar in Montreal whose work has been published in The Globe and Mail, The Atlantic, Fast Company, and elsewhere.

This piece was edited by James Salanga. Copy edits by Jen Ramos Eisen.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director