Movement journalism can transform narratives

When we accept that we are powerless, we foreclose our own radical potential. Stories can change that.

This piece is part of the column series ‘The Case for Movement Journalism‘. Read other column installments here.

In my series on movement journalism for The Objective, I have discussed eight ways journalism that is grounded in community and geared toward liberation can make change in the world – movement journalism, I argue, has the potential to create an archive of resistance; to provide catharsis and healing for storytellers and audiences; to share strategies and inspire action across grassroots networks; to build community and connectedness; to spread political education and help people make sense of the world; to meet community information needs where governments and mainstream journalism have failed; and to spread awareness about issues, candidates, policies, and problems that can lead to concrete change.

These purposes for journalism make up a kind of draft “theory of change” for movement journalism, based on the assumption that if we want liberation and an end to white supremacy and exploitation, we must be strategic in how we develop audiences, use the power of platform, and spread our words through the airwaves and internet. It is not enough to have compelling stories, sad stories, and true stories. We must also develop information infrastructure that responds to the specific conditions and addresses the specific needs of our communities, focused on the people and places most directly impacted by the scourges of capitalism and criminalization.

That strategy is ever more urgent because of how profoundly strategic the people who favor free markets over free people have been. The right wing, aided by the neoliberal wing of the Democratic party in the U.S., has spent decades shaping reality in their favor by developing a comprehensive infrastructure for controlling narratives.

As historian Nicole Hemmer explains in her book Messengers of the Right, conservative broadcasters, book publishers, and magazine publishers began strategizing in the 1940s about how to take their (then-fringe) far-right views into the mainstream by creating their own reputable outlets, while simultaneously using accusations of “liberal media bias” as a battering ram to hack away at even the most centrist media that didn’t conform to far-right views. Their power-building now has its final expression in Fox News, the recent firings of anti-Trump commentators from so-called mainstream media, and the proliferation of radio stations and local outlets trumpeting white nationalist views. Today these outlets, aided by a network of think tanks, educational institutions, and powerful churches, are able to shape the fundamental terrain on which all discussions of politics and policy take place.

Cayden Mak, editor of Convergence Magazine, calls this shaping “pre-influencing.” Because of right-wing media activism, he says, “there’s a conceptual level on which the market economy is sort of the natural resting state of the economy and the marketplace can solve every problem.”

That pre-influence in favor of neoliberal logics “is also what makes it very hard for the left to tell a credible story of what it might be like for us to govern,” Mak says.

Or, as Shanelle Matthews and Marzena Zukowska write in the introduction to their recent co-edited anthology, Liberation Stories, “at the core of every dominant power structure is a narrative foundation.”

These narrative foundations shape assumptions about everyday life, about what is possible, and about how change happens. A right-wing influencer like Joe Rogan — the most popular podcaster in the country — doesn’t have to be heavily “ideological” or political to assert neoliberal logics ideas, Mak explains; his ethos is a result of thorough conditioning in a media ecosystem that took decades to create.

Mak has spent much of his time in the leadership of Convergence Magazine thinking and experimenting with how media organizations can actually transform narratives toward liberation — not just “How do we get a Joe Rogan for the left?”, but “How do we create the conditions where radical left visions for democracy and liberation seem normal?”

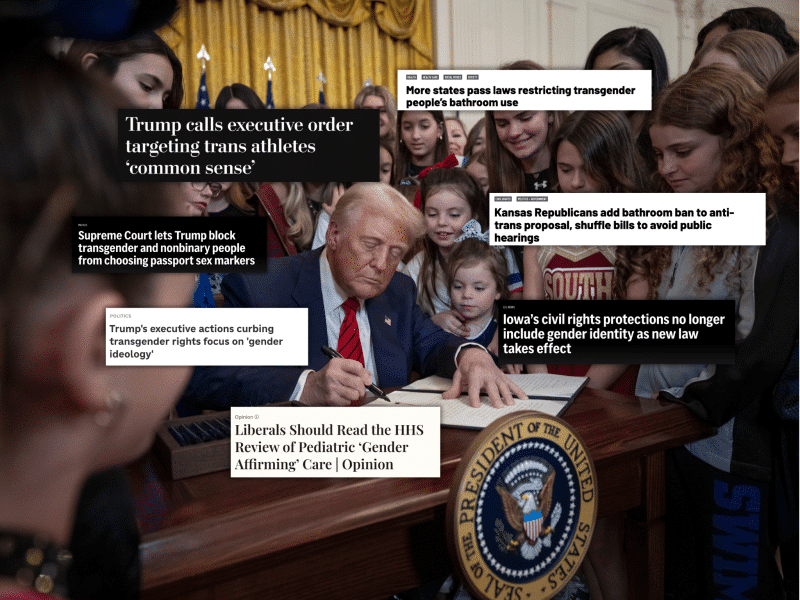

This is a gargantuan task given our 2025 starting point. The daily news is discouraging and depressing; the only alternative is often positioned as simply checking out. And yet we have countless examples of breakthrough narrative shifts, like the Black Lives Matter uprisings that have called into question the entire relationship between communities and policing; the #MeToo movement of the late 2010s that made workplace harassment a household discussion; the gender liberation movement of the last thirty years that has effectively used the internet to undermine the foundations of binary gender and patriarchy in such a way that President Donald Trump felt it was necessary to reinforce the binary gender system on his first day back in office.

To Mak, the ongoing questions are the same: “To transform an information society, you need to be thinking about one, how do masses of people perceive themselves? And two, how are you going to intervene upon that self-perception to help them see different pathways, give them alternatives?”

Transformative media, including journalism, gives meaning to our crappy conditions, and offers alternative visions. The Black Lives Matter movement did this by identifying racism as the core of the project of policing and criminalization in this country, and showing people a vision in which community safety is accessible without police. The gender liberation movement has tapped into and communicated a collective desire to free both identities and bodies from racialized patriarchy. How we perceive ourselves — as victims of an unjust system, as individual free agents, as members of communities, as helpless or hopeful — shapes which stories resonate. But transforming narratives can in turn shape how we see ourselves.

With all of that said, I contend that a single story can never be the source of a transformed narrative. Narrative power, as Matthews, Zukowska, and their many interlocutors show in Liberation Stories, can only be the product of hard, labor-intensive movement building work. Viral moments come and go; narrative shift happens in the pre-influencing, the constant flow and current of stories and information that make a transformed way of seeing the world more possible. Narrative power requires narrative infrastructure, and power over information requires journalistic and informational infrastructure. Building a movement — which the right wing has done with great success — requires coordination and big-picture, big-tent ideological alignment across these goals.

But there are always smaller places for each of us to start. As I argue in my recent book, Radical Unlearning, one of the fundamental assumptions we are pre-influenced by in contemporary U.S. society is that people are stuck in their ways — that change itself is so difficult for people that they will inevitably choose comfort over freedom. And yet this is a narrative that has the obvious effect of discouraging people from trying to change ourselves or make change in our communities. It also naturalizes the political polarization and routine rage that dominate our discourse, by telling people that there is no point in trying to change anyone’s mind, even our own. If you can’t teach an old dog new tricks, what is the point of even trying to unlearn?

I argue that any story that shows people working collectively, changing from an individualist to a mutual aid or community-driven approach, or supporting and defending one another’s freedom has the potential to contribute to a necessary narrative shift. So do stories that explore non-coercive uses of technology in an era of rising artificial intelligence, stories that reinforce cultural practices of resistance to white supremacy and colonialism, and stories that remind us that another world is possible. We cannot expect to transform narratives alone — instead, storytelling that seeks to undermine the culture of neoliberal, technocratic fascism must proliferate in any form we can find.

Together, we can pre-influence our communities towards an overall vision of a world free of authoritarian, fascist, and neoliberal forces dictating our lives based on the interests of capital and oligarchy. This resistance to the reduction of our lives into instruments of a cruel global order is journalism’s purpose zero. While liberals might task journalism with “defending democracy”, it is much more than that. Journalism is also a tool for developing democracy, for connecting and empowering communities, and for shaping what is possible by shaping what we know, how we see ourselves, and how we relate.

Lewis Raven Wallace is the Abolition Journalism Fellow at Interrupting Criminalization and the author of The View From Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity and Radical Unlearning. He lives in North Carolina.

This piece was edited by James Salanga. Copy edits by Jen Ramos Eisen.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director