The resurrected American Penal Press Contest honors incarcerated journalists

2025 saw the revival of the historic journalism awards, once called the Pulitzers of prison newsrooms, after a 35-year hiatus.

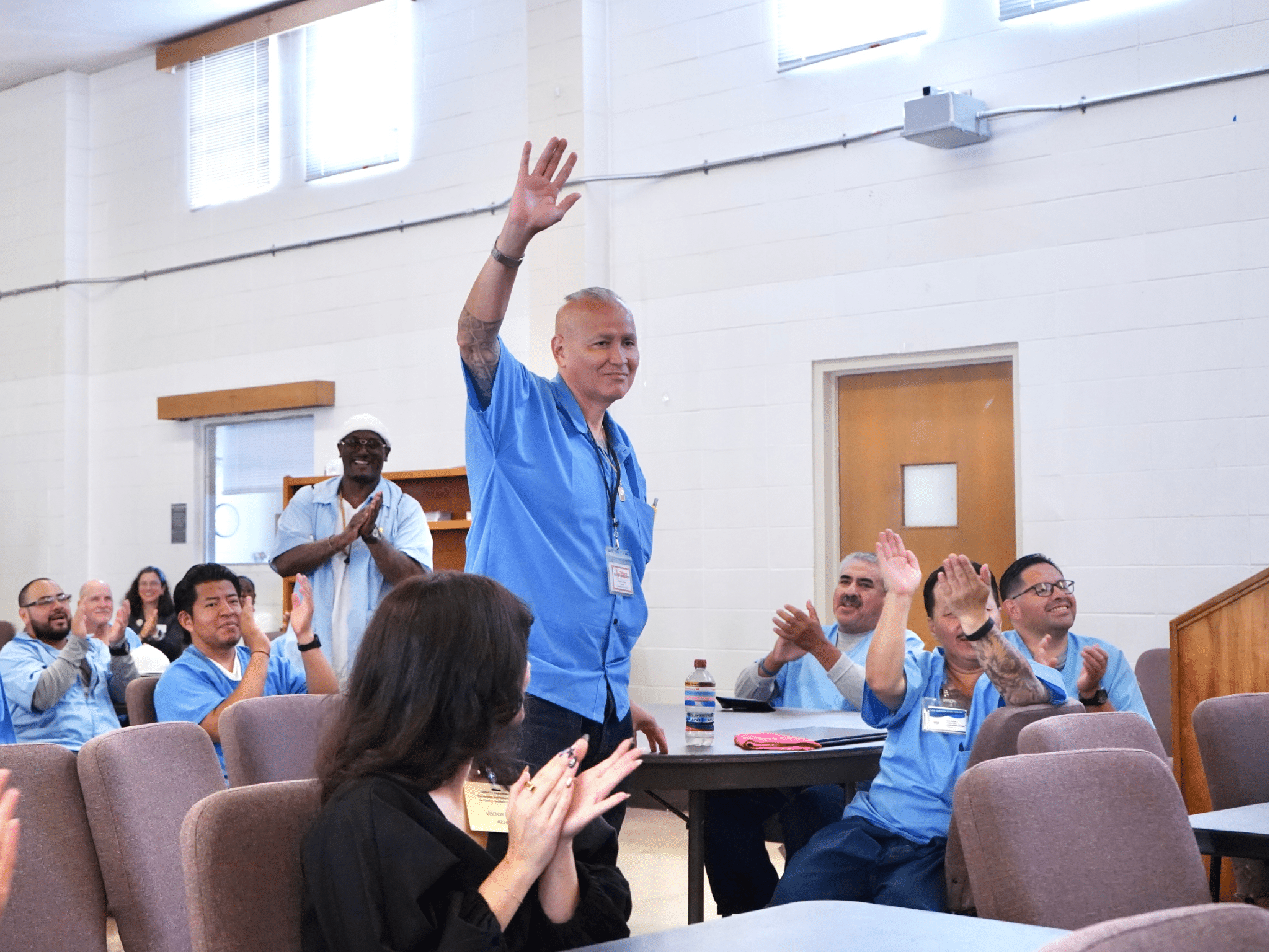

In the brightly-lit auditorium of California’s oldest prison, visitors in business-appropriate suits and dresses gathered with adults in custody donning the conspicuous blue uniforms of the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center on Sept. 19. Others still joined via monitors at the front of the auditorium, their figures compressed into squares on the shared screens. The hybrid crowd had one purpose: to celebrate work produced by incarcerated journalists across the country.

One by one, each of the 14 categories under the American Penal Press Contest (APPC) — from best sports coverage to best debut publication — was read aloud, along with the winning entries. Among the APPC winners this year was Phillip Luna, the editor-in-chief of The Echo and 1664 magazine, both published by the Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution (EOCI). Both publications won first place in the categories for best newsletter and best magazine, respectively, winning a combined total of five awards, including Luna’s second-place win for his editorial on felony disenfranchisement published in The Echo.

“I was pretty floored by that,” Luna said of his team’s accolades. “So many other AICs [adults in custody] and other staff that get interviewed and are just contributing to that all the time — that just felt like the biggest collective pat on the back for everybody.”

As the awards ceremony went on, each nominee and winner stood when their names were called, receiving applause and cheers from their peers. This celebration held deeper meaning: despite the country’s long history of prison newsrooms, the livestreamed ceremony was the first of its kind where teams from multiple newsrooms operating inside U.S. prisons and publishing despite barriers had gathered in one space, even if only virtually. This year’s awards also signified the first held since the APPC’s last contest in 1990.

The contest and ceremony were co-sponsored and revived this year by Pollen Initiative, a California-based nonprofit, and Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. Editorial director Kate McQueen says the livestreamed ceremony was important because it allowed incarcerated journalists across state lines to see and acknowledge one another for the first time.

“People were able to be present and together in a way that I don’t think prison newsrooms have ever really had the chance to be before,” McQueen said.

A long history of the penal press

American prison newsrooms have a storied history dating back to the 19th century. The bluntly-named Forlorn Hope was the first-known publication produced by what we now call the “prison press,” and distributed its first issue inside a New York State prison in March 1800.

Although Forlorn Hope ran only six months, more than 700 prison publications like it have emerged in the centuries thereafter. The oldest dated documents from these publications are articles dating back to 1886 from The Summary, a publication by the New York State Reformatory (now Elmira Correctional Facility), which can be accessed online through the American Prison Newspapers collection. To date, the collection contains 18,338 archival prison newspaper items.

By comparison, the American Penal Press Contest itself is relatively young — founded in 1965. It was the brainchild of Charles C. Clayton, a professor at SIU Carbondale and an advisor to The Menard Time, a penal newspaper published by incarcerated individuals at the Southern Illinois Penitentiary (now Menard Correctional Center), the state’s largest maximum security prison for adult men. Clayton and the advising faculty working with The Menard Time launched the inaugural APPC in part to recognize the work of incarcerated journalists, but also to raise the bar in which prison newsrooms operated, since these newsrooms had little opportunity for feedback.

When the contest first launched, an estimated 222 prison publications were in circulation. One historian described the contest as “the Pulitzer Prize behind bars”, and at its peak in the 1980s, the APPC received more than 1,000 submissions. When prison newsrooms began to shutter and decline — the same time political attitudes were shifting toward “tough on crime” policies nationwide — so did the APPC.

That is, until this year, after the Pollen Initiative teamed up with the university to re-establish the awards after their 35-year hiatus.

“We realized there were these other newspapers out there that were really actively looking for community and hoping for more resources and networking,” McQueen says of her organization’s work to revive the contest.

But putting together a national competition involving incarcerated journalists posed its own unique set of challenges, particularly initiating rapport with correctional officials across the country.

“It wasn’t just about having the newspapers submit their papers for the awards,” Jesse Vasquez, executive director at the Pollen Initiative and a former incarcerated journalist, says. “It was also wanting to get [state correctional departments] to buy into the fact that we could host a virtual ceremony.”

Vasquez’s team secured the support of Ron Broomfield, the former director of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, who helped them approach correctional officials in various states to invite their resident newsrooms to participate, if they had one. Other challenges were coordinating with participants and members of the judging panel, some of whom are also incarcerated journalists. Due to limited access to the internet, competing newsrooms submitted their entries by mail, and judging was managed through paper and digital communications.

This year’s contest drew more than 179 submissions from 21 participating newsrooms, including legacy prison publications such as The Angolite (Louisiana State Penitentiary) and San Quentin News. (The Pollen Initiative started as Friends of San Quentin News, a nonprofit supporting San Quentin News’ operations.)

APPC organizers are already looking toward the next contest in 2026, which will involve changes such as more competitive categories, clearer evaluation metrics, and an updated rating system.

Running a newsroom on the inside

This year’s awardees included Luna and Cris Gardner, who netted a first-place win in the best long-form magazine story category, have taken winding paths to editorial leadership at their respective publications.

Luna remembered first arriving at EOCI in 2015, having never been involved with the law: “I was pretty naïve,” he said. “I really kind of struggled for a long time.”

That changed when he answered a job ad at the facility for the role of a newsletter clerk. Despite no journalism background, Luna figured that his penchant for reading would translate to the job well. He went on to steward The Echo and 1664 magazine, and now leads a rotating team of writers to produce the monthly and quarterly publications.

The launch of 1664 last year has allowed Luna to pursue more ambitious stories and fulfill what he sees as his role as a journalist in the system.

“I don’t know that people realize, but life still happens inside,” he said. “People still have kids who grow up, they have grandkids … there’s cancer survivors, there’s veterans in prison, there’s Gold Star parents. I think as incarcerated journalists, we have access to that in a way that most reporters never have access.”

Gardner, who helps run Nash News and NC News Today, wrote for his high school newspaper as a kid, but was initially roped in as a graphic designer — which he jokes he was “completely unqualified for.” He returned to his love of writing by pitching story ideas for the Nash Correctional Institute (NCI) publications. One of his first pieces was a recipe article he molded into a features-style profile in the vein of the New York Times’ Sunday magazine. “If I can tap into a person and I find a little something that I can write a story on, that’s when I’m excited the most,” he said. The 54-year-old, who has been serving time at NCI in North Carolina since 2007, saw his team’s quarterly publications win nine awards at the APPC.

As newsroom leaders, Luna and Gardner deal with the same headaches that other newsroom leaders on the outside do: They manage their newsroom’s resources, edit their team’s stories, and mentor newbie writers who are just getting their feet wet. But unlike most newsroom leaders, they must contend with barriers that come with running a publication inside a carceral facility. Issues like restricted mobility and severely outdated equipment have disrupted Luna’s team’s ability to meet publishing deadlines.

“Technology is a huge hurdle,” Luna said. “Writers can learn to write, take good photographs, but if we can’t put it together, there’s no publication.”

Deeper challenges entail systemic attitudes toward adults in custody among some of the state department’s officials.

“There are people in the administration that are going to try to make sure that you remember that you’re incarcerated. That you did something wrong and you don’t deserve to have half of the things that you get,” Gardner said.

Because publication hinges on approval from the Department of Corrections (DOC), there is also an issue of looming censorship: “Sometimes we want to write a story that’s … maybe negative towards the DOC,” Luna said. “Sometimes we have some issues with that, and so we have other ways to publish things, like working with [nonprofit partners like] the Prison Journalism Project.”

Despite these hurdles, both newsrooms have larger ambitions: Luna wants to commission stories from incarcerated writers at other facilities within EOCI’s state system, and Gardner seeks to establish full-time paid roles for his team to produce NC Prison News Today and Nash News.

“There are some really talented people out here that are incarcerated … most of them are being defined by their worst moment rather than by the potential that they possess. Being able to highlight their stories and put them out there has been a true blessing,” Gardner said of his work with the papers.

Looking ahead, Vasquez said he hopes the contest can build a wider community network for more prison newsrooms.

“I think the prison population is tired of just doing time for the sake of doing time,” he said. “[These newsrooms] want to give individuals something to look forward to.”

Natasha Ishak is a freelance journalist covering politics and public policy based in New York City.

This piece was edited by James Salanga. Copy edits by Jen Ramos Eisen.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director