Media layoffs are a recurring pattern. How can we stop them?

Journalists should not be wondering when they’re going to be laid off next.

This piece originally came from The Front Page, our twice-monthly newsletter on that examines systems of power and inequity in journalism. Subscribe here.

We may be in a new year, but a number of journalism trends persist — including layoffs.

If you’re involved in the media world, odds are that you’ve heard of the job cuts that have occurred last month. In the past 30-something days, publications of all sizes and mediums have been affected, including the LA Times, the Wall Street Journal, Sports Illustrated, TIME Magazine, National Geographic, TechCrunch, and Business Insider. The high-profile media startup The Messenger, on the last day of the month, also announced it would be closing after less than a year, leaving 300 journalists without jobs.

Why does the media industry keep finding itself in a position where journalists — regardless of experience level — are unsure of their future?

In his 2024 Nieman Lab prediction for journalism, Robert Hernandez almost-prophetically stated that “the wrong people will be laid off… again.”

Hernandez argued that responsibility shouldn’t fall on workers. Instead, he wrote, “What has continued to fail is the leadership and executives running the business. […] What I’m saying is it’s time to hold our business executives accountable. […] How often do these executives face consequences, like a general assignment reporter in the newsroom? Chances are they’ve gotten bonuses and raises, while newsrooms fight for better pay.”

Related: After Kevin Merida’s surprise exit, will LA Times’ new editor listen to the paper’s owner or its workers?

The Messenger had $50 million to its name when it launched last year and claimed it could raise twice that amount this year. Its founder, former The Hill owner Jimmy Finkelstein, insisted that the publication would be different and the company desired to reach an audience of 100 million monthly viewers. This pressure was reflected in the quality of the site’s content. Eli Walsh, former breaking news reporter at The Messenger, wrote on X that the majority of the stories he wrote at the outlet consisted of “copying and pasting work that other reporters put time and effort into […] for the sake of driving traffic at any and all costs.”

This unsustainable model led to the publication lost $38 million dollars last year. Ultimately, the staff bore the brunt of this loss — a pattern reflected by other newsrooms.

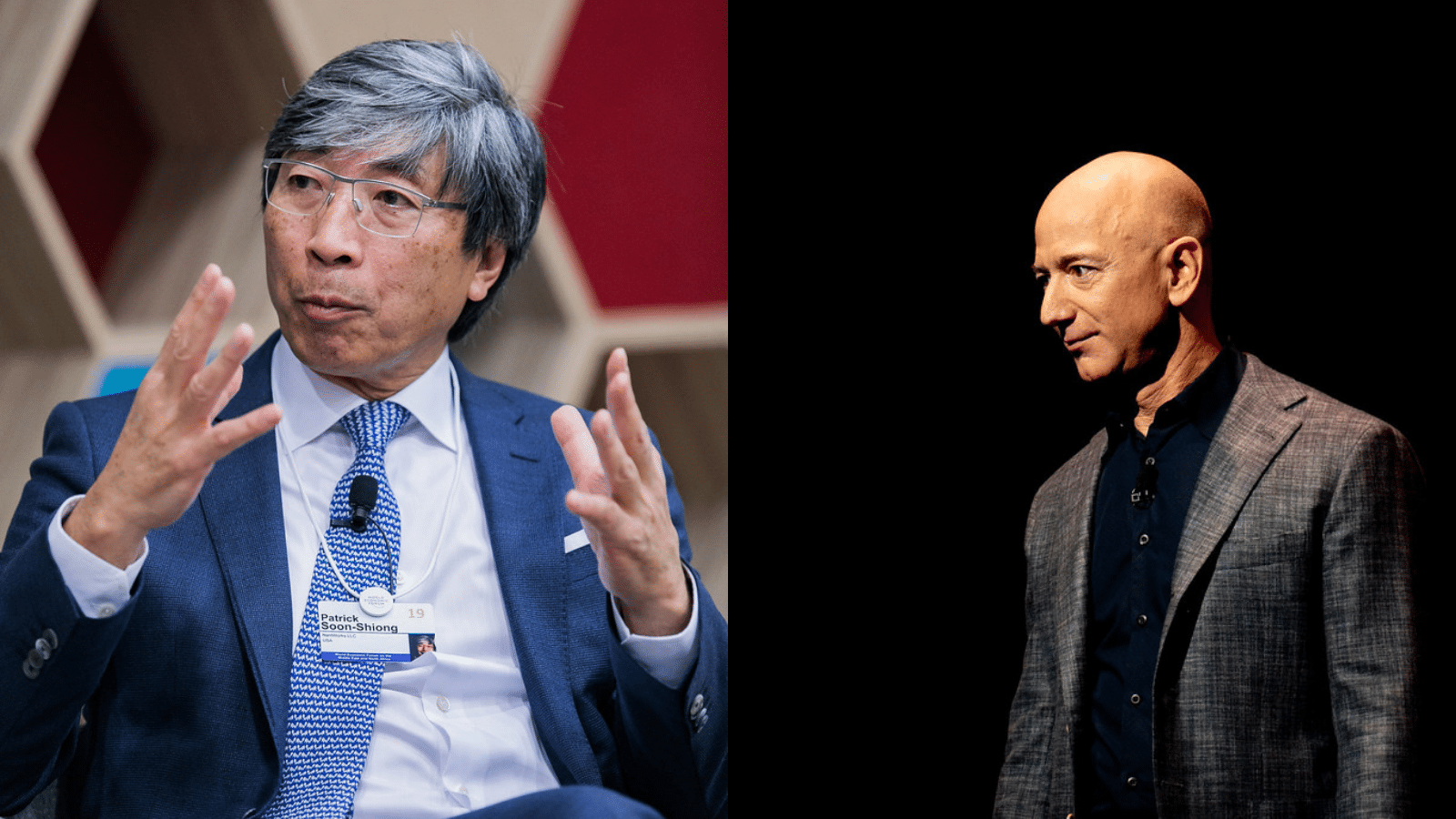

The LA Times layoffs, which the paper’s owner Patrick Soon-Shiong attributed to cost-cutting as the newsroom saw financial losses, if they continue as planned, created a major loss of journalists at the Times’ Washington bureau. And according to Erin B. Logan, a journalist who was recently laid off from the LA Times, the publication “laid off every single Black person in its Washington [b]ureau.” De Los, an initiative focused on Latino issues, was also among the teams affected by the layoffs.

We are currently in an election year, which means it is especially important to keep an eye on what is happening in Washington, and as Nieman Lab notes, De Los was an effort to connect with an audience typically overlooked by the LA Times. It is alarming when a large number of laid-off journalists are of color or are focused on minority communities.

Related: ‘No long-term vision’: after layoffs, staffers say L.A. Times lacks plan for future

What does all of this mean for journalists who have suddenly found themselves without a job? Freelancing may seem to be an obvious option, but it is not the solution.

As a writer who has been a freelancer for the vast majority of my journalism career, I believe it is very difficult and is filled with uncertainty; it really is not for everyone. As Jewel Wicker, an Atlanta-based journalist, elaborates, freelancing comes with its own set of issues, including the pressure to pay for your own medical care. It is great for those who decide they want to do it or have the capability to, but journalists should not be forced to freelance to remain in the industry.

In the midst of these layoffs, media workers have been circulating mutual aid resources in order to support their peers. Some include emergency grants, the LA Journalists’ Mutual Aid Network and the community aid network.

Last month also saw a number of labor actions: Employees at places such as Condé Nast and the New York Daily News went on a one-day strike last week to protest contract negotiations. Unions can be helpful in the face of mismanagement due to power in numbers — in fact, former The Messenger workers are suing the publication’s founder for the sudden layoffs, and the NewsGuild of New York is suing Sports Illustrated’s publisher for the layoffs being alleged union-busting. But there still needs to be a fundamental change in how we can make news sustainable and which business models prevail.

Publications are businesses, but it feels that executives often forget the humans who are working to produce the stories. Journalists should not be wondering when they’re going to be laid off next.

Houreidja Tall is an NYC-based journalist and culture writer who explores the stories of communities that are disregarded by traditional media and shows the nuances in their experiences.

This piece was edited by James Salanga. Copy edited by Jen Ramos Eisen.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director