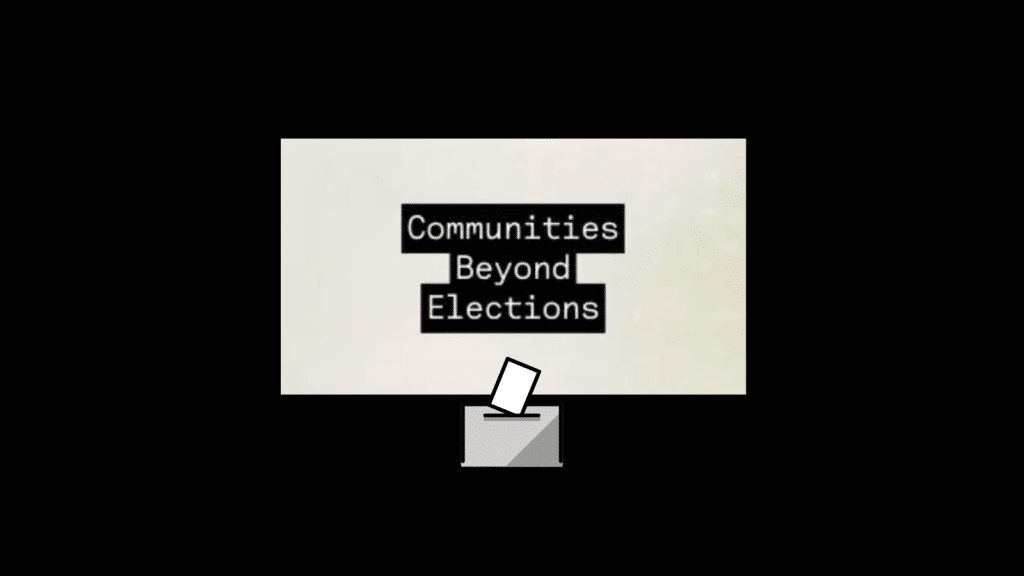

Q&A: Communities Beyond Elections

Da’Shaun Harrison and Lara Witt, both involved in co-founding the Movement Media Alliance, spoke about movement journalism, decentering politicians, and what it would take for newsrooms to shift their election coverage.

Newsrooms and reporters are bracing for the ascension of an anti-press president who spouts racist, xenophobic, and transphobic rhetoric by examining the ways their coverage contributed to his election.

Mainstream newsrooms often cover electoral politics by repeating politicians’ rhetoric and language. Newsrooms also often reduce communities to monolithic voting blocs — the youth vote, the Latino vote, and so on — whose everyday issues are only examined in relation to their importance in elections.

“What if instead, election coverage shined a light on the stories of and from the communities politicians use for votes?” writes Scalawag Magazine’s co-executive director Da’Shaun Harrison in their introduction to a new project: Communities Beyond Elections.

Focused “on people, not on politicians”, Communities Beyond Elections is one of two initiatives launched under the auspices of the Movement Media Alliance, a coalition of 17 different publishers including Scalawag Magazine, committed to movement journalism. (The other is Media Against Apartheid and Displacement, a hub for anti-apartheid and anti-genocide coverage, which The Objective is also a part of.)

The Objective spoke with Harrison and Witt about how their effort is grounded in movement journalism, what it would take for newsrooms to shift their beliefs about what election coverage should look like, and more.

This interview has been condensed for length and clarity.

For those unfamiliar with movement journalism, how would you describe it?

Da’Shaun Harrison: I know Lara and one of our co-workers, Maya, wrote a brilliant op-ed a couple months ago that detailed the history of movement media.

Movement media is designed to build a bridge between on-the-ground movements and media that has largely been violent towards and misrepresented folks who have been organizing on the ground.

For me, the importance of movement media is that it allows for there to be some sort of perhaps unspoken reconciliation between the two groups, particularly because, again, movements have largely been disrupted or violated or harmed by legacy and mainstream media. And this is our attempt to disrupt that harm.

Lara Witt: Movement journalism has a loose definition from several organizations, but the one we use the most often is from Project South, and it’s “journalism in service of liberation.” So not only does movement journalism look to provide the historical context of the roots of oppression, but it seeks to undo them at the same time.

So much of journalism, especially mainstream journalism, … will address who, what, when, where, and then the why will be either based off of the journalist’s perspective or the publication that they work for, the one that they would like to push.

And so it leaves out the perspectives of marginalized folks who first and foremost know and deeply understand the why of the things that are affecting their communities.

So what we try to do at each of our individual publications, the ones that are members of the Movement Media Alliance and who are participating in the Communities Beyond Elections initiative is to continue to push movement journalism so that we can really seek to undo the injustices that we continue to suffer from.

How does Communities Beyond Elections aim to bridge communities and a news media that has and continues to harm them?

Harrison: Election coverage every two to four years is always about what the politicians will or will not do, what politicians have made promises about or have failed to do. And so often, it leans on the particular “voting blocs” that are actually made up of real people who are experiencing actual harm year after year. A big part of what is driving this initiative is that we want to make clear our focus is always … on the communities that we write for and with, that we cover, that we live in, that we experience a day to day life with, irrespective of what politicians are or are not doing, irrespective of whether or not politicians are showing up for us or not.

Our communities have a very deep understanding, a very clear understanding of the experiences that they have and the violence that they’re facing in the world, largely because of the politicians that get too much attention every two to four years.

… Narrative has largely been co-opted by mainstream and legacy media as a way to disrupt any real way of life for our communities. It has been used as a tactic for centuries as a way to sort of cement colonialism and to cement the policies that politicians have often used to oppress and suppress our communities.

CBE is an initiative to undercut that. To say, you know, if the Atlantic Journal-Constitution and Cox Media are going to cover Cop City in a way that is on behalf of or in favor of the city’s misleadership, then we’re going to represent the organizers who are disrupting that.

If the New York Times is going to cover reproductive rights … or a loss of trans rights in a way that’s going to harm or rather, reaffirms politicians’ rhetoric, we’re going to actually be engaging with other trans people, with other folks who experience a lot of the violences of reproductive justice or reproductive rights. And we’re going to make sure that their voices are heard instead. That’s the primary focus.

Witt: Our communities are also really well-positioned to have the solutions to the issues that we’re tackling. So CBE is not just about presenting the effects of oppression, but also the solutions to them — whether they are decarceration efforts, whether it is ensuring that there is a system to protect migrant folks, undocumented people, whether it’s ensuring that trans folks have access to the care that they need, whether it’s mutual aid for folks who are dealing with debt or displacement.

… The more that we’re able to connect these stories to each other … we can really start to shift a narrative of powerlessness to one of empowerment and creating actual sustainable change.

There’s also confronting the fact that, you know, objectivity is completely a myth. … It’s going to result in a lack of truth. The New York Times has been pushing its anti-trans narrative for 10 years, maybe a little bit more than that. Now they’re going to have to cover the very real effects of their journalism on trans folks. Same thing with manufacturing consent for genocide. These are the things that they do under cover of so-called objectivity.

What are some of the limiting beliefs around electoral politics and our political structures in general that you’ve seen play out in mainstream journalism?

Witt: The way that journalism covers electoral politics is usually in service of the politicians themselves — [whether it be the] DNC platform [or] RNC platform. … Writing negatively about politicians or questioning the things that they push, as well as their policies or lack of policies, usually limits the sort of access that they [journalists] then have, which then affects the kind of journalism they’re going to end up doing.

… It does a disservice to journalism as an industry itself, which already has really poor reader retention, and leads to a very easy crumbling and breakdown of journalism, where we see, you know, lower subscription rates, lower ads for for-profit entities that then rely on billionaires buying them out, and then the billionaires ultimately end up having control of the publication.

The most recent example of that is what’s happening at the LA Times with their owner having a lot of control and editorial say, which is just inherently unethical in so many different ways. We’re seeing a breakdown of the establishment and journalism as a part of that establishment.

It’s really up to readers and media consumers as well as movement journalists to present an alternative. CBE, as well as our other [MMA] projects, are a place where people can find their reliable information, because if they can’t find it fact-checked and well-sourced and really rigorous within journalism spaces, they’re going to start relying on conspiracy theories and social media only, and just get sound bites that are devoid of context. That then leads you to a pipeline of bullshit into a funnel of alt-right stuff to then just sheer fascism.

The more people are disinformed, the more that they’re scared, the more we see fascism become ascendant, which is what we’ve witnessed in the last 10, 15 years.

Harrison: There is this general narrative, I think, or at least one that is budding, that’s coming on the back end of a decade since the start of the BLM movement, where folks are like, “Okay, how we engaged electoral politics for these past 10 years has not worked.”

So the question then becomes, then what do we do?

What I think is happening now is that movement media is in a very specific space. We’re having to counter the ways that fascism is being built on the backs of fear from people who have either, for a long time, felt the need to move further and further right, or who don’t have any real clarity on what it means to move further left — while also navigating cutting through the noise of neoliberals who have made it their business to support establishments.

Witt: Movement journalism is also a form of political education. We’re providing people with a critical lens, a critical analysis to look at the systems they live within, and to be able to read a piece at like, NBC, that’s parroting anti-trans narratives.

It’s our responsibility to give people the tools for media literacy so that they can spot like … manufacturing genocide shit over at the NYT just within a minute of reading a piece just by being able to identify, who did they source? Who wrote the piece? How come the person who wrote that piece lives in a place that ejected Palestinians from their home in the 1970s and the 1980s? How come so many [news bureau chiefs] happen to have strong ties to the [Israeli Occupation Force] IOF?

We need our readers to be able to ask those questions.

Can each of you share a few pieces from CBE that have published so far and talk about how they relate back to the project’s ethos?

Witt: Elias Guerra, who is a freelance reporter for us, recently wrote on the heavy burden universities place on Muslim women students. He spoke to multiple Muslim women students across universities in the U.S. who have been subjected to racist backlash, Islamophobic backlash, the fact that they have very little support systems within their schools, the fact that the administration seemed not just unsupportive, but also actually really violent towards them.

These are some of the perspectives that we want to continue covering, because so much of the election cycle itself was just looking at Muslim American communities in the U.S. as a voting bloc. And the fact that the genocide [in Palestine] was a major reason for why they [the Democrats] were losing Muslim American voters.

We’re looking at the effects of American policy both at home and abroad, how it funnels down into academia, and how it’s going to continue affecting Muslim students throughout the U.S. … What we’re doing is naturally folding our communities within our coverage on a regular basis because … these are the people who are our friends, our families, our communities, people that we do movement work with.

Another piece I wanted to highlight was low-wage workers in the food service industry not being able to afford to eat. … Wage theft, underpayment. The minimum wage across the U.S. is a major electoral issue, but it’s not one that they [the Democrats] actually pay attention to.

… The intersection between immigration and migrant rights and undocumented workers, and then the actual effects of capitalism and racism and anti-immigrant sentiment and how it affects migrant workers within large factories — whether it’s by deaths, getting crushed, getting pieces of their limbs pulled off, [or] using children as workers — these are all issues that should be front and center within people’s economic policies when they’re running for elections, but they don’t give a fuck.

… So CBE’s responsibility is to continue to ensure that our communities are being covered accurately. They’re providing them with the safety of decent reporting, because a lot of outlets don’t necessarily provide their sources with decent cover or anonymous standards that they completely understand. And it can be an extractive experience to be a source for journalism, so we also want to ensure that across our outlets that our sorts of editorial standards have a throughline there of ensuring that it is a mutually beneficial endeavor to pull these pieces together.

Harrison: One [CBE piece from Scalawag] is “Election myths ‘The Left’ tells about the South”. Really, the entire purpose of this piece is to talk about the ways that in order to disrupt fascism or to end fascism, you have to end America [as it exists]. And that the reality is that neither party is interested in stopping fascism because neither party is interested in stopping America and ending America.

The frame that this piece is written through is the fact that … from Hitler to the South African apartheid, they learned their tactics through the spread of slavery in the Black U.S. South. So many times, people don’t actually talk about or don’t fully understand the ways that slavery, and therefore, the ways that Blackness is perceived today.

Slavery, eugenics, and Jim Crow … continue to play a significant role in global politics, and therefore also play a significant role in the ways that the … political climate is created and sustained.

The other piece that I have thought a lot about is about the Democrats feeling entitled to the youth vote. … After the election, there was a lot of commentary that I saw [on social media] from people who were angry about or angry with Gen Z, either because they felt that Gen Z voted a little too conservatively or didn’t vote at all. And I thought that it was interesting to see that so many people felt that the litmus test for Gen Z’s political commitment to liberation was whether or not they voted for Kamala Harris.

This piece was just like, you know, the Democrats feel like they’re entitled to the youth vote and the reality is that they aren’t, right? As you start to engage an entire generation of people who are perhaps more politically aware or at least politically engaged than prior generations were, you have to actually consider their needs and their wants.

… As somebody who is … in both of these spaces and communities [as a Black Southerner and someone who was a Black youth], I always find it interesting in the ways that the Black South can be so easily dismissed, disregarded, removed from any sort of political analysis, despite the fact that the Black South plays such a significant role in how the entire globe’s politics are constructed.

I’m going to throw out a third piece … about the way that trans folks from Alabama were already thinking about the election, the ways that they already knew how the election was going to go, particularly because of the ways that trans folks in Alabama have been ridiculed and violated and harmed so much by politicians in the past several years in particular.

That piece feels very important to me, precisely because trans politics were so central to a lot about how the election was covered this year … even down to the way that folks were talking about Kamala’s loss.

… But a lot of trans folks have, for the longest, been talking about the ways that politicians on both sides of this bipartisan political spectrum have harmed and violated us and have not had our best interests in mind. And so that particular piece … honors that through a very southern lens. It makes clear that if there is an answer for trans people, it is not going to be found through an election.

For newsrooms that are interested in learning more about this lens of covering marginalized communities beyond just as data points or as voting blocs during elections every two or four years, what do you think would be necessary for them not to fall into this weird identity reductionist coverage that we’ve seen from the Obama administration, during the “2020 reckoning”, and so on?

Witt: If there are large swaths of the population that you are not including as your journalists, as your editors, as your sources, as the voices that you … rely on to share tips and stories, then what you’re doing is continuing to promote a very white supremacist settler-colonial agenda where the only voices that matter — whether you say it out loud or not — are the ones that the ones that are white, the ones that are cis, the ones that are able-bodied.

So I understand that seems like a very hard line thing for me to say, but it’s just a natural, normal thing to want to include marginalized communities within your reporting.

Because it’s doing a service to journalism itself, it’s taking into account the truth about this nation. It’s the same thing about teaching history accurately. If you’re hiding and censoring what has actually happened within this nation, what happened to make this nation, then it’s not really history.

It’s just a hyper-censored version of whatever you want to continue promoting. It’s propaganda … to continue maintaining legitimacy of the state. Because the more people understand the violence that came and continues to be state-making, then they would be up in arms … So these newsrooms are going to continue to just maybe throw a token piece here and there, but they’re not actually intent on completely changing the makeup of their newsrooms.

They’re not intent on actually looking at how their newsrooms have continued to perpetuate old lantern laws, the way that their newsrooms continue to proliferate and ensure that incarceration rates continue to skyrocket across the country, because it would threaten their comfort and their existence.

So I think that there are many ways for newsrooms to implement the changes, but they’d actually have to politically, internally, emotionally, as human beings, want to have change within their country, within their country, within their states, within their towns.

But the people who are most often staffed within newsrooms don’t actually want to create any of those changes … and that’s not to say that there aren’t wonderful reporters at mainstream and legacy newsrooms. There are some that just do absolutely fantastic, wonderful work. I just wish that they would work elsewhere.

Harrison: Since the Obama era, identity politics have been manipulated to reshape the world of politics and has been used by politicians as a way to manipulate. And we see that through DEI. But I think what’s also true is that journalists and media spaces have also used that very same tactic … as a way to sort of prove their allegiance to marginalized people. As we enter into this next Trump era, we are going to really see what newsrooms are actually committed to marginalized identities and what newsrooms are not.

Because Trump is coming for us, right? He is coming to disrupt DEI. He is coming to disrupt newsrooms. He is coming to disrupt nonprofits.

And if you do not have an actual commitment to marginalized people, you will very quickly and very easily get rid of your DEI department. You will very quickly and very easily get rid of the token marginalized people that you have hired to cover these communities and you’ll stop covering our communities.

But for those of us who are actually committed to marginalized identities, not only because we embody those identities, but also because our newsrooms are made up of those people, we won’t have the option to run away from or to remove any sort of semblance of these marginalized identities from our spaces.

If newsrooms are going to try to implement these actual ideas where they actually want to cover our communities in a way that is not them sort of committing themselves to the violence of identity politics — and I’m saying it that way because I don’t think identity politics are inherently violent, but that the ways that they have been manipulated are — they have to actually build their newsrooms around our people, our communities. Not just asking a couple of marginalized people to write or to perform in a way that just reifies or reaffirms white supremacist logics.

Oftentimes what we’ve witnessed over the past decade, at least, is that has been the request. You can show up as this particular marginalized identity, but you must perform, still, as we would ask any other white, cis, able-bodied, Christian, etc., person to perform. And if you don’t, then you’re out the door.

That’s going to be something that they [newsrooms] really have to confront over the next few weeks, months, years, if they’re going to actually survive, if they’re going to actually have their staff survive.

James Salanga is the co-director of The Objective and the podcast producer at The Sick Times.

This piece was edited by Gabe Schneider.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director