Make it make sense: movement media as political education

Even when our stories herald bad news, they can also include context and analysis that helps people make meaning of the story and figure out our role in responding.

This piece is part of the column series ‘The Case for Movement Journalism‘. Read other column installments here.

For years now, friends and I have looked at each other wide-eyed when we talk about the news, confounded and angry: it doesn’t make sense. Why would a local government want to build this massive fake city for police training in the woods, in the middle of a climate crisis, a homelessness crisis, and a crisis of police violence? Who’s pushing for this? None of it makes sense. Why Trump’s rise, why Israel’s unyielding attacks, why organized abandonment, why Elon Musk’s fame, why AI data centers?

Movement media can’t provide complete answers about the politics and motives of the moment, but can at least attempt to put the pieces together — the root causes, the historical context, and who benefits. In “This is the Atlanta way: a primer on Cop City,” published in Scalawag in 2023, Micah Herskind — an activist based in Atlanta — offers an explanation of “the city’s corporate and state ruling class actors who have demanded that Cop City be built” and a history of land ownership and the politics of development in the city. Bit by bit, for the reader, the inexplicably bad idea that is “Cop City” begins to make sense, as does the urgency and strategy of the struggle to stop it. This is movement journalism as political education: a way to explain our world beyond simply relaying the bad news to readers.

Political education is the process through which we learn to understand our material conditions, their root causes, and our own role in building the worlds and societies we want. By seeking to understand these underlying systems and structures while analyzing power and who benefits from oppression, we can see the roots of harm and hopefully develop better strategies to unearth it, a process called root cause analysis. Traditions of popular political education often draw on theater, dialogue and debate, and self-reflection and storytelling to help people work through our relationships to power and oppression and arrive at a new perspective that enables action.

But political education also happens to us passively throughout our lives — possibly most importantly, through the news. In the U.S., people spend an estimated average of 70 minutes per day consuming news in some format (that number hasn’t been updated since 2010, and has likely grown), with more than ⅔ of adults in 2024 saying they “closely” follow election news. Through a mix of digital, print, television, and radio news, we receive not just information about our political world, but framing about our roles in it. Most mainstream media, as a part of the performance of “objectivity,” focuses on partisan political debates and “rule of law.”

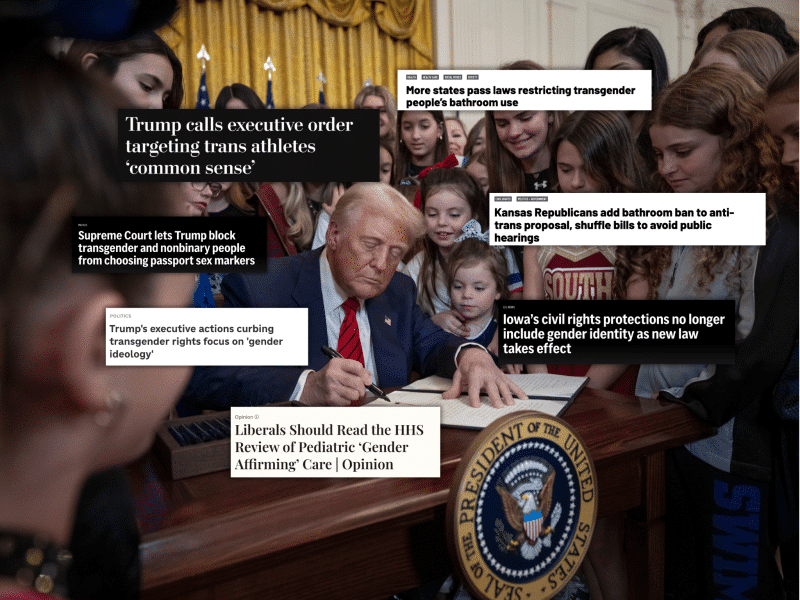

Mainstream media also teaches us to accept existing systems; for example, coverage of Trump’s mass deportations often highlight whether or not someone has a criminal record, rather than human rights violations or the root causes of migrations and borders. Coverage of climate change usually zooms in on response and mitigation, rather than the companies profiting from burning fossil fuels or those companies’ efforts to quash mitigation. Coverage of police violence often takes a “both sides” framing that gives a platform to police to make an argument in favor of extrajudicial violence and promotes the falsehood that police are a source of public safety.

Related: Better immigration reporting starts by questioning assumptions about migration

Many are frustrated, disillusioned, and depressed as we read and watch these stories. Political education through movement media provides a refreshing alternative: Even when our stories herald bad news, they also include context and encourage root cause analysis that helps people make meaning of the story and figure out our role in responding. In the long term, this makes all news potentially more relevant and meaningful. Even when a movement media worker may not have space or time to explain years of context of a given story, writing with a radical political analysis can connect readers to a deeper understanding of the structures and relationships to power in anything from stories about basketball to stories about war. Movement media organizations can also take the role of helping people better analyze and interpret mainstream news reports.

The Kansas City Defender, an abolitionist, Black-run news outlet founded with young Black audiences in mind, has always seen political education as a key goal.

“We view ourselves as a community media organization, or an organization that also happens to do media,” said founder and executive editor Ryan Sorrell. “The political education is central to every aspect of the organization.”

The KC Defender grew out of the 2020 uprisings, when Sorrell, born and raised in Kansas City, moved back from Chicago to his hometown and found huge gaps in community organizing and information — particularly for young Black residents in Kansas City.

Reaching these audiences with relevant stories was straightforward for Sorrell and the small group of teen and 20-something Black youth who launched the outlet. One of the Defender’s first popular stories, headlined “Yes, I’m Still Pissed That Slaves Were Held & Sold Out the Basement of Kelly’s in Westport”, laid out the history of a popular, mostly-white bar for young KC residents: Kelly’s had once been a holding cell for enslaved people.

In the article’s blunt language, Sorrell appeals to people to stop going there — and uses the shock factor as an opportunity for political framing: “The continued presence of the building is violent, anti-Black, and a daily reminder of Kansas City’s unapologetic past and present white supremacist terrorism.”

The brash voice and intelligent analysis of the KC Defender echoes the outlet’s inspirations: Black study, fugitive study, and radical Black outlets like the Chicago Defender and the Black Alliance for Peace. Movement media need not be abolitionist in order to provide political education — but abolition, as a political vision, provides a more comprehensive explanation of the why and how of our political moment than many liberal and progressive interpretations.

“Context is a huge thing that is left out of a lot of traditional media,” Sorrell said. “They’ll just report on things as if it happens in a vacuum. I think that’s a political education opportunity.”

Everything from how a story is framed to the history provided and the choice of language and terminology can convey — and potentially shift — a political perspective. For KC Defender, the goal is to shift towards abolition, getting rid of terminology like “law enforcement” and “inmates” and forcefully pointing out the inherent violence and anti-Blackness of U.S. legal systems.

“Political education keeps us from reinforcing … harmful narratives. It keeps us from reinforcing carceral narratives, from reinforcing imperialist narratives,” Sorrell added. “If we don’t have political education, then we will inevitably reinforce these. We’ll use their language and their framing and we won’t provide the context that’s necessary for stories. Our framing won’t be liberatory.”

Even the KC Defender’s social media posts are treated as an opportunity to reframe stories for their audiences. When the US launched airstrikes on Iran in June, the Defender’s Instagram thread explained three distinct points: what happened, how it relates to Missouri (the war planes were flown from an Air Force base near Kansas City), and the Defender’s analysis of why.

Sorrell has also found that their popular stories are often the ones that reiterate news with a different audience in mind — the younger Black people who follow their social media accounts and attend the Defender’s many public cultural events in the city: “We don’t have to be the ‘breaking news kind of organization’ because even if the Kansas City Star does break the news … they don’t have a way of reaching young Black people, so we can still come days later with our analysis and it will be reaching the audience that we’re able to reach for the first time.”

Earlier this year, the Defender expanded its political education by offering a freedom school, B-REAL Academy (Black Radical Education for Abolition and Liberation). The first cohort had 20 students ranging from age 11 to age 73; the second cohort is kicking off in late August. Their approach to Black radical political education operates on the assumption that the people directly affected by oppression are the ones who can best understand and explain its root causes.

“Even high school Black students had a far more robust racial understanding than the editor-in-chief of Fox4KC or the Kansas City Star, because of their lived Black experience,” said Sorrell.

None of what’s happening makes sense until you understand the reasons behind our current armed, violent state: Settler-colonial power, racial capitalism and slavery, and structured abandonment and neglect got us here. Shared clarity on the nature of these systems is a necessary foundation for any movement to get us out.

As Aja Arnold of Mainline said, “Abolitionist media offers the framework necessary to people to really understand what’s going on. [It is] the soft space to land to say, like, ‘Hey, actually, a lot of that is bullshit.’ Not only is the existing system killing people unnecessarily, and causing all this havoc and chaos — we actually have visions for how the world could be.”

Lewis Raven Wallace is the Abolition Journalism Fellow at Interrupting Criminalization and the author of The View From Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity and the forthcoming title Radical Unlearning. They live in North Carolina.

This piece was edited by James Salanga.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director