How does a story go from ‘spreading awareness’ to making concrete change?

Movement journalism needs a theory of change in order to affect policy and practice.

This piece is part of the column series ‘The Case for Movement Journalism‘. Read other column installments here.

Many well-intentioned activists and writers come to my office hours and events with ideas for stories or podcast projects that they hope will “spread awareness” about something — a specific injustice, or sometimes a whole community or issue (e.g. “I want to spread awareness about gentrification” or “this project will spread awareness about queer people in the South”).

My first question is always: Who are you trying to make aware? My second question is: Why?

These questions cut to the core of the theory of change — or lack thereof — that is common in most mainstream U.S. journalism. The assumption within most newsrooms is that with information and awareness, people are moved to participate in civic and political life, taking action based on shared understandings of what is true. Or, for politicians and the powerful, the assumption is that once they’re aware of the harm their decisions cause, they will make different political choices either due to conscience or embarrassment. Generally speaking, this theory of change assumes that once the public is aware of an injustice, lie, or act of hypocrisy, they hold those in power accountable — or that the people in power self-correct out of shame.

But much of my recent study of the science and social reality of unlearning has shown me the fallacy of those assumptions. Information alone rarely changes minds, nor does it have a tendency to directly spur action. And politics in the U.S. have clearly moved beyond national politicians changing their actions out of any sense of shame when caught in a lie or exposed as a hypocrite — there are likely still exceptions in local and state politics, but nationally, the shame ship has sailed. Plus, there is the problem of information overload: Even the most politically active people are generally “aware” of more problems than they can possibly take action around.

These limitations to conscience and introspection are just the beginning of the problem of mainstream journalism’s theory of change. The idea of spreading awareness to make change happen also contains a slew of unspoken assumptions about the audience, what they know and don’t know, and what they might feel about the information being presented. If you constantly face racism, will a story about the constancy of racism be a revelation? Conversely, if you are racist, will a story making you aware of the harms of racism spur you to act differently?

This series of columns has attempted to lay out a “theory of change” for movement journalism, beyond “spreading awareness” about issues that matter. But that doesn’t mean spreading awareness is pointless: It works best when it occurs across specific fault lines of access and power. So, when our stories aim to spread awareness, we should ask: To what end? Awareness for whom? What is the relationship between the story as you plan to tell it, and the audience you want or need it to reach? And how can that awareness spur action and consequence? These questions can inform an overall praxis for our journalism, which should observe and respond to the real structures of power in which we work, rather than abstract assumptions about our audience.

For example, the work that Palestinian journalists have done to raise global awareness of what is happening inside of Gaza since October 7, 2023 has been necessary to spark global outrage and action. Within the U.S., journalists in prisons have made rich use of reporting and storytelling to raise awareness with people on the outside about their conditions, whether they’re speaking out on solitary confinement, climate crisis, or forced gender conformity.

Related: The UN called it genocide in Gaza. Will Western journalists dare to?

These situations have common characteristics: The people inside Gaza, and inside prisons, are aware of conditions that have been concealed from the public beyond those being targeted directly, and the people who have the power to challenge and change these conditions are either unaware or complicit. Spreading awareness has an acute and urgent goal, and acts of journalism that reveal atrocities and violations can become immediate tools in the hands of activists.

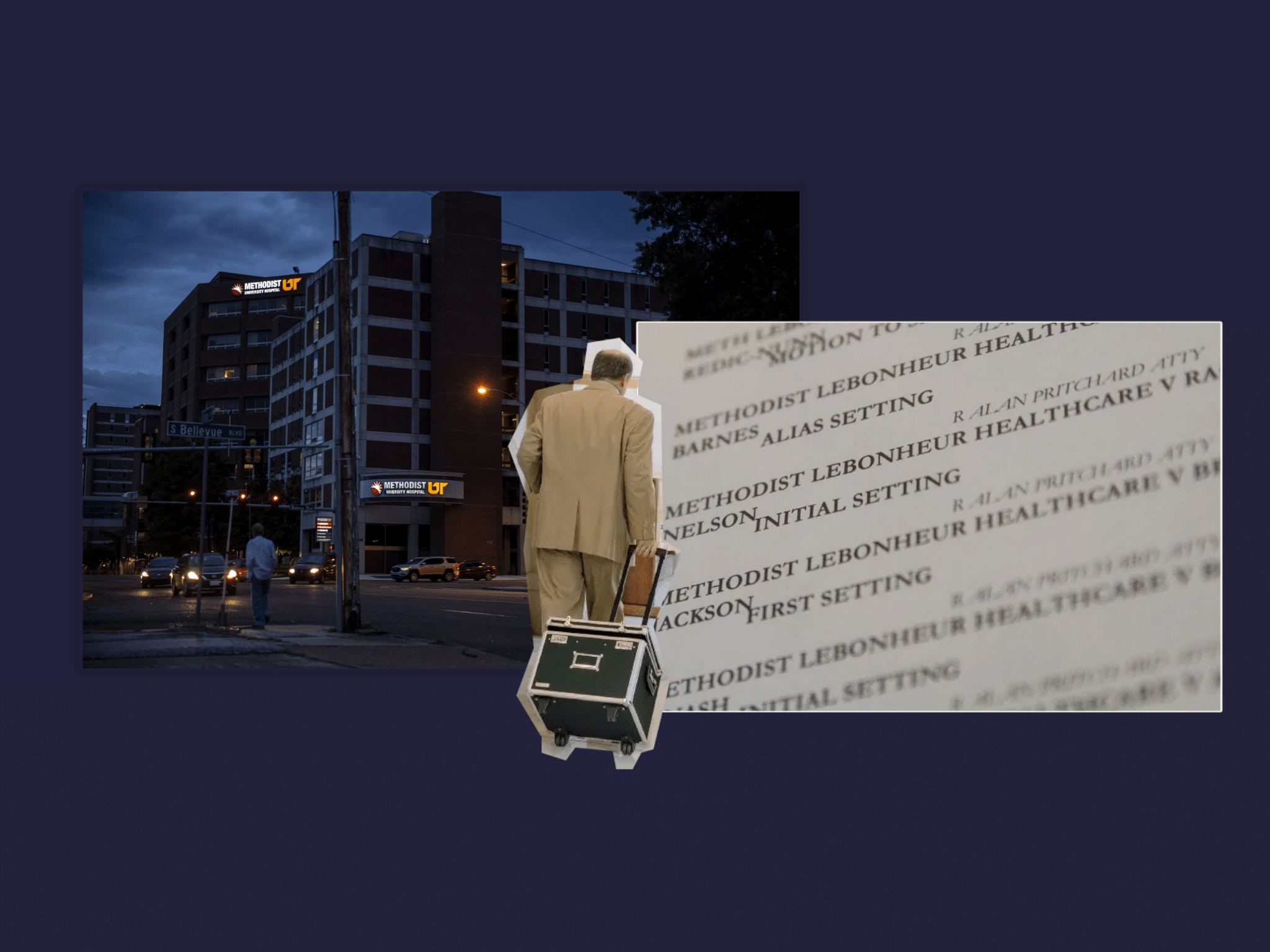

Investigative journalism is the other avenue through which awareness can translate to action: Investigations do more than just raise a problem, but, as Wendi Thomas of MLK50 told me, good investigations “document that people are being harmed and identify who’s doing the harming.” In other words, investigative reporting may eventually raise awareness about an issue, but the reporter first takes care to get to the causal root of the problem. Their work doesn’t just name a problem, it points at the specific people responsible.

“I think if you approach poverty as a theft, then you’re looking for the thieves,” Thomas said. “Sometimes the actors can be obscured, so you don’t even really know who was screwing you.”

That was precisely the scenario with her bombshell series, “Profiting from the Poor: Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare and Debt Collection” which revealed that a Christian hospital in Memphis was bankrupting low-income Memphis residents with thousands of lawsuits over medical debt. After the stories’ release in 2019, she says, “the reaction was swift,” partly because it outraged residents at large and humiliated hospital officials, and partly because many of the people facing the debt didn’t realize the hospital had a choice about whether to sue them. In the reforms that followed, nearly $12 million in debt was erased. The hospital also raised wages for its own workers, some of whom were making far less than living wage and had been sued by their own employer over medical debts.

The best way to make spreading awareness into an achievable and meaningful goal of our journalism is to tie it to accountability: Identify both who is affected and who is responsible, as Thomas did for the medical debt investigation; gain an understanding of who needs to know about a problem who doesn’t already; and then activate and inform the groups most likely to put pressure on the powerful and hold them to account. Here, journalism takes a page from the activist’s book, whether or not the journalists consider themselves activists. Spreading awareness becomes a link in a chain of solidarity that can lead to concrete change.

Lewis Raven Wallace is the Abolition Journalism Fellow at Interrupting Criminalization and the author of The View From Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity and the forthcoming title Radical Unlearning. They live in North Carolina.

This piece was edited by James Salanga. Copy edits by Jen Ramos Eisen.

We depend on your donation. Yes, you...

With your small-dollar donation, we pay our writers, our fact checkers, our insurance broker, our web host, and a ton of other services we need to keep the lights on.

But we need your help. We can’t pay our writers what we believe their stories should be worth and we can’t afford to pay ourselves a full-time salary. Not because we don’t want to, but because we still need a lot more support to turn The Objective into a sustainable newsroom.

We don’t want to rely on advertising to make our stories happen — we want our work to be driven by readers like you validating the stories we publish are worth the effort we spend on them.

Consider supporting our work with a tax-deductable donation.

James Salanga,

Editorial Director